Languages and other textual peripheries

Patricia Couvet is the laureate of the fourth edition of the TextWork Writing Grant.

Having spent some time working in so-called “foreign” languages (English and German), there have been instances in which returning to my “native” language (French) has proven linguistically tedious. It was always a matter of adjusting to different registers—I was either too formal in private, or too casual in professional settings. The subject of plurilingualism and language practices became even clearer to me after conversations with artists Fatma Cheffi and Hussein Nassereddine and graphic designer Garine Gokceyan, all of whom were guests of the program at Pickle Bar—a space I co-founded in Berlin1—in 2024 and later while talking to artist Mégane Brauer and graphic designer Walid Bouchouchi.

Unlike other languages, French marks a conceptual difference between “langue” and “langage”2: the first refers to a set of rules relating to the lexicon of a given linguistic system, while the second designates someone’s ability to express themselves and communicate. This distinction, when attempting to translate it into English—the second language this text is published in—calls for the use of more elaborate linguistic concepts. One could, for example, rely on the translations of one of the pioneers of modern linguistics, Ferdinand de Saussure, for whom the difference between langue and parole (in English: language and speech) sets orality as a personal gesture, more liberated and diverse than a linguistic system.

This phenomenon outlines a limit well known to those whose accent is often corrected when speaking, whose oral distinctions are systematically erased when writing, and whose speech—whether plurilingual or slang—is marginalized in the name of a univocal rhetoric. A language can be subverted, edited, and reinvented by poetry and typography. Jean Genet, for example, argued that it is “ridiculous to use quotation marks around slang words and sayings, because that is how you prevent them from entering French language”3, showing how, out of defiance or fear, the way we use a language can be a reaction to its normative framework and its performative and textual forms. The emergence of these methods in the fields of visual arts, performance, and graphic design forms the starting point of this text.

The artists and graphic designers discussed in it all explore in their own ways, through typography, writing, and performance, a unique relationship to language—to what is traditionally not acknowledged within the frame of the page—that can be found in the physical space surrounding the main text, a place where a symbolic detachment from language norms settles in. Multiscript, plurilingualism and ties between oral forms and writing create conditions for utterance and speech formation in which non-normative forms of language are possible routes to follow, invitations to hijack or distort what appears to be the prescriptive limits of a language.

Pirating Language to Make Way for Other Uses

In July 2024, artist and curator Fatma Cheffi was invited to perform at Pickle Bar. For the occasion, we bought a decorative Zulfiqar, a double-edged sword often depicted in Shia iconography, to be engraved on its blade.4 The Zulfiqar is also represented on the flag of famous pirate Khayr ad-Din Barbarossa, the image chosen for the event’s press release. Throughout her lecture-performance, Cheffi references the mythology of Barbarossa and the way his character has been remembered as independent. In the performance Steal, Steel, Still Fatma, the artist spent fifteen minutes handling the sword with one hand and the text with the other. Her gestures were restricted by the heavy weight of the weapon, contrasting with the lightness of the sheets of paper in her other hand. The text was handed out to spectators ahead of the performance in an invitation to read collectively, sharing the experience of a restrained language. Educated in both French and Arabic in Tunisia before moving to France for university and eventually enrolling for a postgraduate degree at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Lyon, Cheffi lists in her reading some of the stereotypes linked to her name that she discovered upon moving to France: that of a domestic worker or a prostitute, stigmatized by the colonial and post-colonial job market, constantly reminded of her place in society.5

According to philosopher Judith Butler, “by being called a name, one is also, paradoxically, given a certain possibility for social existence, initiated into a temporal life of language that exceeds the prior purposes that animate that call.”6 The linguistic injury inflicted by the insult affects the body as much as the mind, including the muscles of the tongue, so much so that the surprise following the name-calling could paralyze and force into silence. Cheffi notices: “While mistakes in Arabic are hardly noticed in Tunisia, mistakes in French often lead to mockery and humiliation. It is some kind of terrorism. A linguistic terrorism.”7 “Linguistic survival,” as suggested by Butler, settles in when in spite of discourses that might harm or deny it, an existence affirms itself, claiming recognition within and through language—an act of resistance in the face of the norms trying to erase it. To the symbolism of the forked tongue—a metaphor for the one who does not stand by their word—represented by the Zulfiqar, Cheffi adds that of a tongue that is stunned or wounded when it is corrected or revised, or when it trips from one language to another.

“I’m not from my home or from yours,”8 sing PNL, a French rap band formed in 2014 that Cheffi often references in her work. The feeling of being foreign and surviving coexists with the feeling of wriggling between many tongues and languages. Throughout the lecture-performance, the artist’s personal memories are interwoven with a set of references to popular culture (religious and musical) and media sources (including Instagram TikTok posts) referencing linguistic imaginaries,9 and more precisely the value granted to French and the implied social hierarchies of colonial language in Tunisia and in France, which enforces a logic of assimilation and centralization. The performance offers a kind of confidence, a moment of intimacy and collective listening that allows tongues to loosen and words to flow freely during this designated moment of exchange between the audience and the artist.

“Pirating” encompasses both the notion of intruding into an established system, but also a way of sharing music, videos, or text files online with peers. It’s mainly this second meaning of the word that inspires Cheffi’s linguistic proposal: an effect of hybridization and dispersion of a language circulating outside official networks. It is through this process that the word seum drifts from its original meaning of “poison” in Arabic to mean “rage” or “frustration” in French. A historical example, the Mediterranean lingua franca described by historian Jocelyne Dakhlia, composed of various languages from the Mediterranean region in the seventeenth century, forms a pluralistic linguistic tool, originating from a blend of languages used by merchants, sailors, slaves, and convicts, who often hailed from antagonistic areas. This plurilingualism worked as a place for negotiating with the Other, breaking from a universalist, dominant perception of language. This served as inspiration for artist Simone Fattal’s Pearl (2023),10 a work made of blown glass beads of different sizes, on which lines from an anonymous poem in lingua franca have been manually engraved. Here Fattal turns poetic language into a vessel for the memory of colonial and postcolonial stories in the Mediterranean, which Cheffi integrates with narratives of migration and the diasporic languages of our generation—born in the 1980s and ’90s and raised on lyrics from French rap and R’n’B widely broadcasted in France and in the Maghreb.

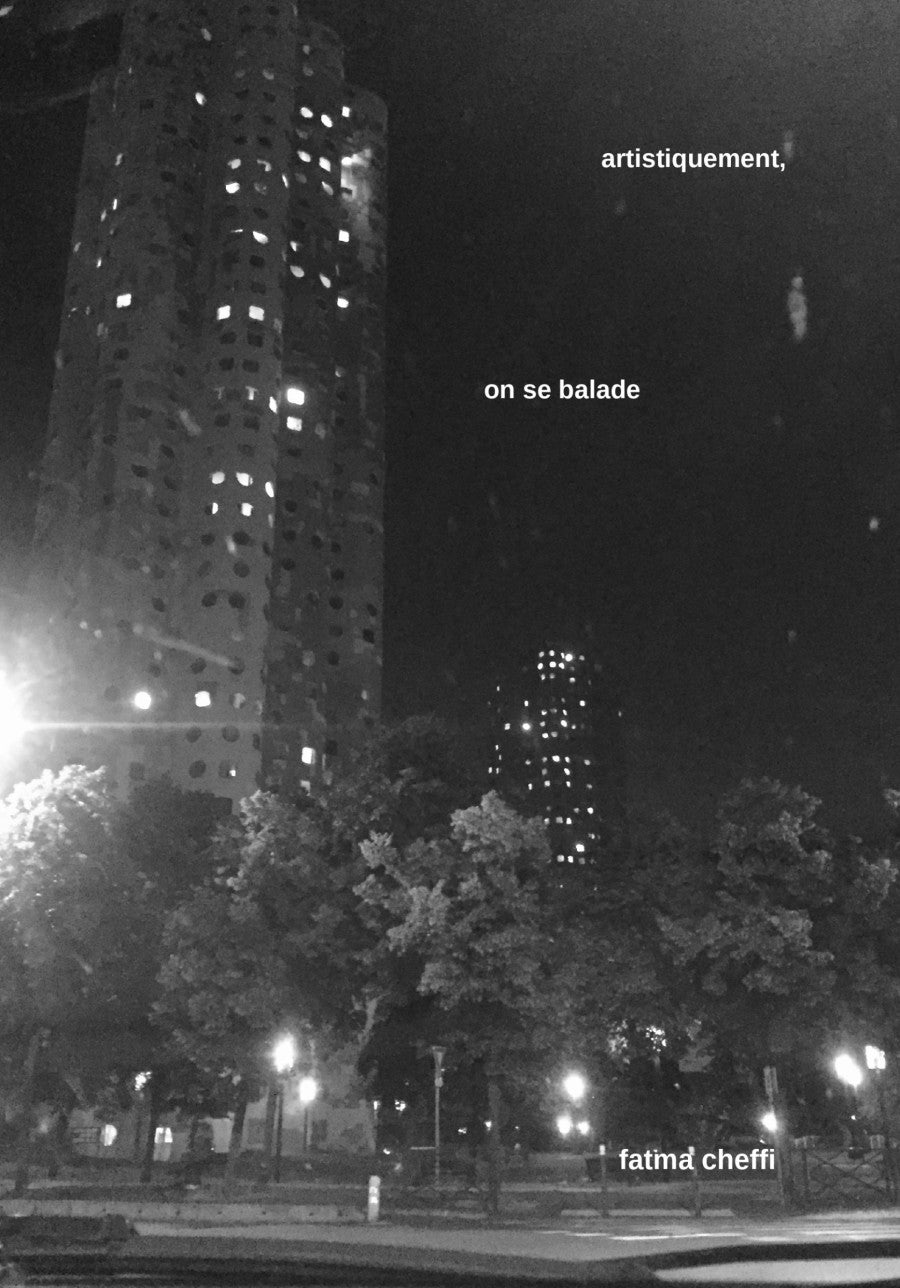

Published on the occasion of Cheffi’s project Bastardie at Kadist in 2024,11 the fanzine Artistiquement on se balade (Artistically we’re cruising) brings together screenshots, snapshots, and pictures of PNL concerts, which have been archived, collaged or resized until they became pixelated. These are “poor images,” blurry, distorted, or cropped to fit the compressed format required for their distribution, as argued by artist Hito Steyerl in her 2009 essay of the same title.12 These low-quality images set the political and social conditions for a subversion of market logic and dominant/elitist cultural standards. There is something similar in the language Cheffi advocates for. Just like the “poor” image, this language transforms itself: it breaks down syllables, cultivates barbarisms—from the latin barbarismus (“vicious expression”), meaning “language mistake,” and, by extension, “word of foreign origin”—and multiplies phonetical permutations as often heard in French rap.

For the event Triple S in June 2024, Cheffi invited writer Diaty Diallo and socio-linguist Cécile Canut, who has written about how “the language order” is a normative system stemming from institutions (the Académie Française, the school, the state) that creates hierarchies and demotes linguistic uses that stray away from this institutional frame.13 Linguistic rambling and the pirating of official forms make way for the emergence of a vocabulary for a new generation of writers supporting a Nouveau Réalisme, whose words are a way to inscribe in literature, poetry, and visual arts, among others, a language representative of a society that is actually plurilingual.

Cheffi refuses the terms plurilingualism and multilingualism because, according to her, they do not mirror the reality of a language within which different accents, tones of voice, and registers form a hybrid language adjusted according to context.14 Expressing ourselves in one language can lighten the feeling of alienation that connects us, for various reasons, to one another. Code-switching describes the intentional choice made by some multilingual speakers to consciously use another register or another language that they master so that a dominant language can become a way of acknowledging minority languages. English, in particular, sometimes has this neutralizing effect, because it is the main language of contemporary artistic practice and critical discourse. Cheffi often writes her texts in English. Daring to write in French is a way to assert that the colonial language is not untouchable, but can be claimed as your own through the strategies mentioned above.

Translating Without Betraying

Recently, I noticed that quotations marks differ depending on the language (« » in French or „ “ in German, for example), as if modes of enunciating depended on a national issue, a distinction from one language to the other and that these languages could never meet within a text. Theodor W. Adorno saw in quotation marks a kind of “interplay that takes place in the interior of language, along its own pathways.”15 A dialogue in which the written word is defiant of spoken language, while paradoxically trying to recreate with its audience a relationship similar to the one they have with speech. There is a similarly interesting goal in multiscript graphic design, a common practice which involves the coexistence of multiple alphabets, for example in multilingual countries. In France, it creates a graphic proximity between many non-official but widespread languages and alphabets.

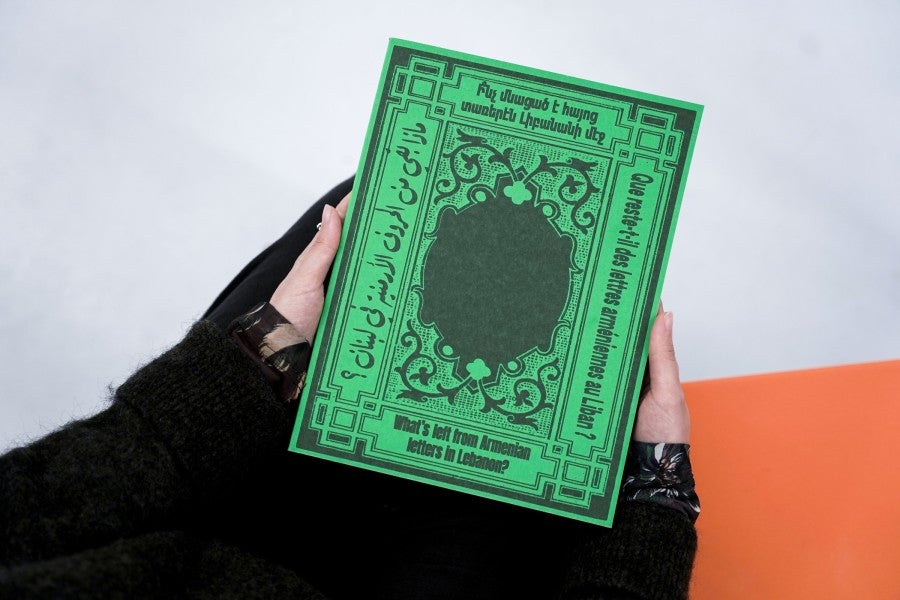

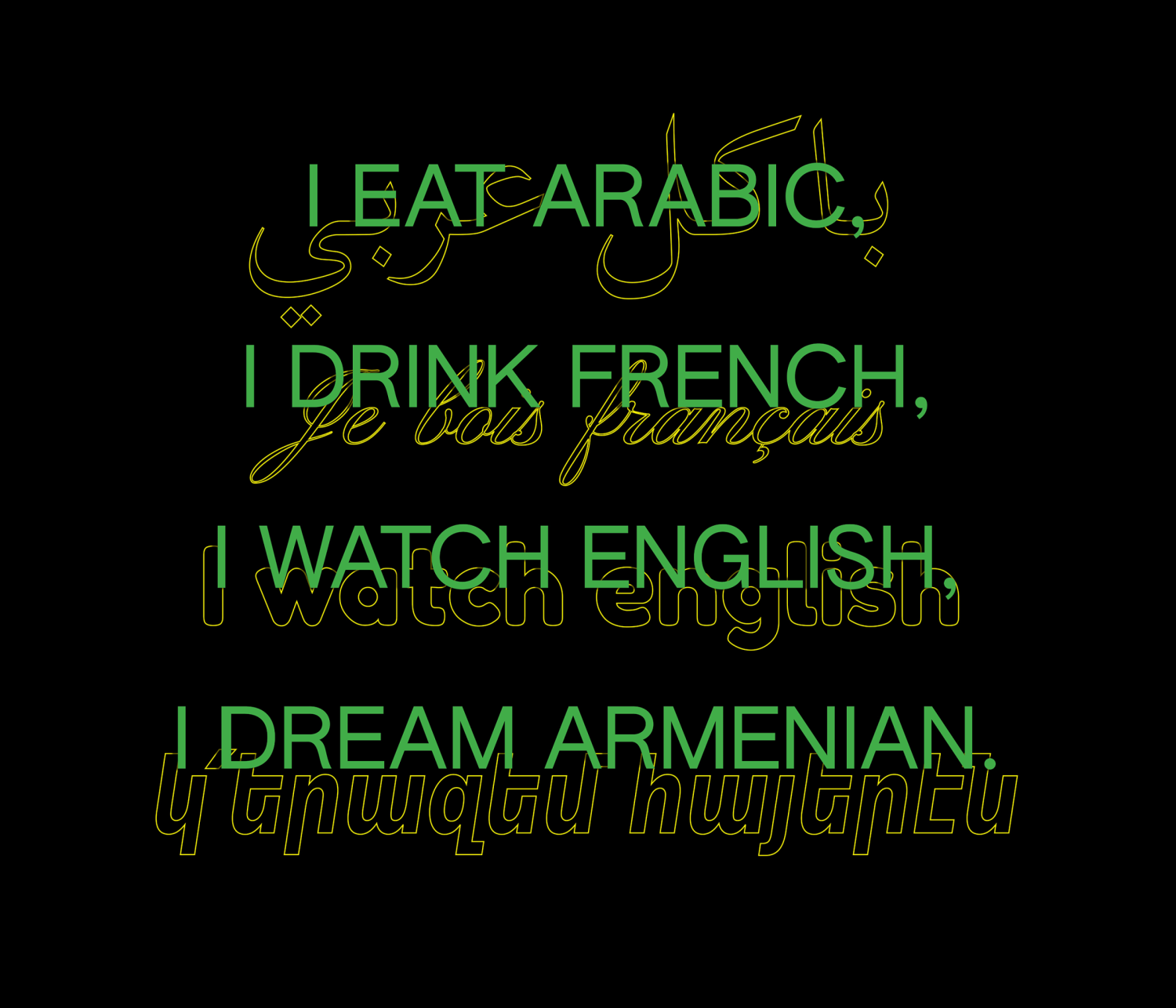

The program Sturm and Slang, organized at Pickle Bar in 2024, invited Garine Gokceyan to create, in collaboration with Kadist, a visual for a T-shirt. On the back of the shirt, the pun “Traduttore, traditore” is written in four languages: Italian, Armenian, English, and Turkish. This figure of speech, coupling words based on their sonority and spelling illustrates the impossibility of a faithful translation and shows that no translation is possible without losing nuances or meanings unique to the original language.

That same year, Gokceyan was invited by graphic designer Walid Bouchouchi (Akakir Studio) to Festival Tangible, in Marseille, to give a conference on multiscript—specifically discussing Armenian in Gokceyan’s work and Amazigh and Arabic in Bouchouchi’s. “I never chose to be plurilingual” begins Gokceyan when talking about her multiscript work. There remains a belief that, to a plurilingual person, one language is always supposed to take over another and it is easy to imagine that a minority language will be less spoken in a homogenizing context such as the francophone space. The plurilingual person is expected to rely on strokes of luck, such as similarities or phonetic correspondences between languages.16 In graphic design, “unfortunately, we still have to use the Latin matrix and the ‘Swiss’ international style remains a reference in designers’ education, even in Lebanon, where multiple alphabets coexist. It’s a real effort of conceptual and visual deconstructing,” explains Gokceyan. Her words remind me of the story of early twentieth-century Syrian painter Selim Haddad. His plurilingualism as well as his knowledge of calligraphy allowed him to create the first Arabic typewriter, inverting matrixes from left to right and switching from Latin to Arabic, thus escaping the Latin constraints of writing technologies.

For the design of the visual identity of the exhibition Habibi, les révolutions de l’amour (Habibi, the revolutions of love, 2022–23) at the Institut du monde arabe in Paris, Bouchouchi created an inclusive version of the exhibition’s title by adding a ligature to the second B, thus integrating the feminine form: habibti. The ligature—the fusion of two or three letters with the aim of creating a new one—between the B and T of habibi/habibti becomes a gesture of union, exposure, and a typographic representation of the LGBTQI+ community.

Another exhibition could have had the title “7abibbi”—a nod to Arabizi (from “Arab easy”), a hybrid form of writing used by the Arabic-speaking world and by its diasporas, weaving together Latin letters and numbers for easy use of phone keypads and make way for sounds absent from the Latin alphabet, such as the letter ح (Ḥāʾ, the first letter of حبيبي habibi). But this would have been a separate conversation: the widening of horizons and exchanges promised by the technical innovation characteristic of the history of the internet, meant as a modernist utopia, in which a universal language would translate and globalize everything. Gokceyan and Bouchouchi both insist that multiscript in the French-speaking world appeals to both to a Latin-language-reading audience and to the plurilingual diasporas, and it is precisely this middle ground that allows multiscript to make its way in the graphic design scene. What proved fascinating about Arabizi is that it allowed dialectical Arabic to inhabit writing, a space thus far only meant for literary Arabic, and in turn switch registers.17

To the plurilingual person, constantly going back and forth between languages, drawing from multiple schools and graphic references, multiple diasporas and artistic scenes, creates the possibility of an inclusive language, inspired by research in different visual cultures. For Gokceyan, graphic research goes hand in hand with linguistic research, because it can create a linguistic bridge between eastern Armenian (spoken in Armenia) and western Armenian (used by the diaspora). If language constitutes an element of one’s identity, Gokceyan’s typographic and visual research also allows for the reconstitution of a fragmented identity.

During the conference “Auditive Voyeurism” with artist Mekhitar Garabedian at Pickle Bar, Gokceyan presented a slideshow of images showcasing different writing systems coexisting in public spaces in Lebanon, such as storefronts, or verses from the Quran calligraphed in paint on the back of transport trucks—images that could be found in our smartphones, the result of a type of voyeurism for approximate translation. Multiscript bears the promise of a translation where typography sublimates meaning and mistakes become manifestations of subjectivity. Such an idea ties into what philosopher Paul Ricœur calls “language hospitality,” meaning the idea that a target language (the one being translated into) does not dominate the source language, but tries to welcome what is foreign. This constraint on the page is precisely what multiscript practices explore. Gokceyan and Bouchouchi make multiple writings coexist, for all those who dream in a language in which they feel more free than in the one they use daily.

A Language Facing Its Disappearance

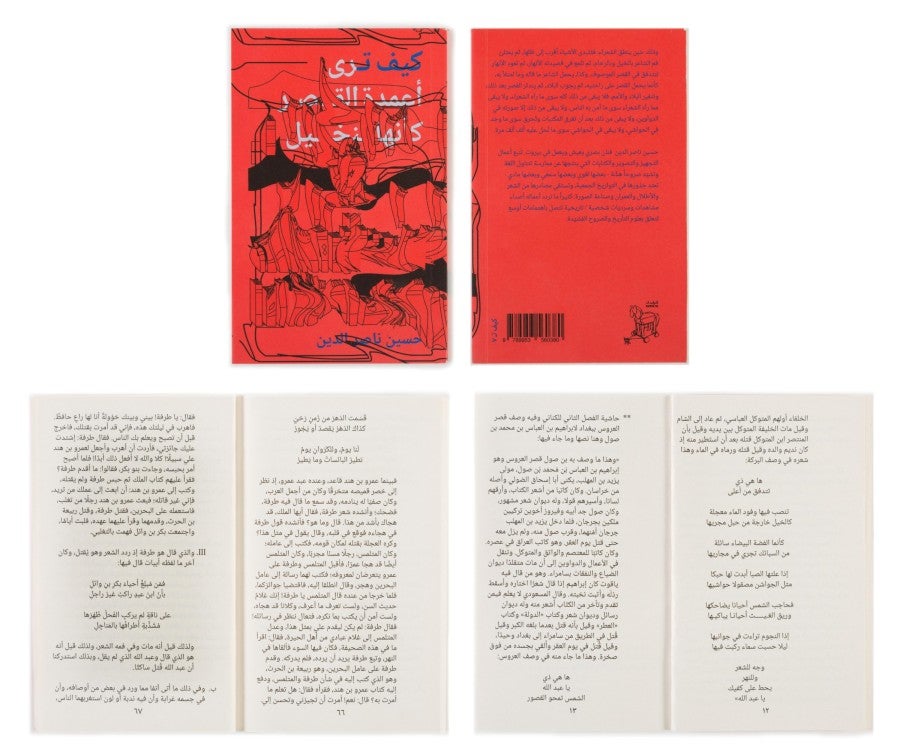

Some margins outline a text, some argue against it or, conversely, graphically circle it to emphasize it more. In his book How to see the palace pillars as if they were palm trees, published in Arabic in 2020 by publisher Kayfa ta and recently translated into English (2024), artist, graphic designer, translator, and poet Hussein Nassereddine tells the story of poet Abdallāh-The Slain (Abdallāh al Qateel), said to have lived during the seventh century, although exact dates have been contradictory across various sources. The original book telling his story is no longer accessible, likely lost, but Nassereddine discovered the story in a single verse, later putting together references to it scattered throughout various glossaries and poetry anthologies. Abdallāh-The Slain allegedly died following his last vision: a hallucination in which he pictured the pillars of a palace as palm trees. This image tells a metaphor common in Arabic poetry, illustrating the poetic gaze’s ability to transform reality.

Intimate bonds tie the sometimes anonymous editors, translators, and other commentators of a single text. Their role is to adapt and convey it using their own words. How can we archive this intermediary process, of copyeditors, editors, who intervene in the interpretation of a text, who choose the format of its transmission? In margins—“the negative space” of the book, as Nassereddine calls it—sources that should never have met come together. Rather than calling for the revival of a literary canon, the artist archives a narrative marginalized by historiography, that of poets facing the disappearance of their own words and their replacement by others.

The reconstitution of the story of a forgotten poet indexes the linguistic layers through which a text is reinterpreted. I use the term layers because it isn’t unusual to look at languages from a geological and anthropomorphic perspective in order to describe their transformations through time. A language can disappear. It can fade into oblivion, die. There are logics of deliberate violence: the erasure of a culture, the illegal occupations of colonized regions which contribute to the exclusion of certain languages or forms thereof. As shown by the story of Abdallāh-The Slain, books are fragile physical supports and their disappearance comes with that of the author’s word.

In his work, Nassereddine often sets up spaces where speech can unfold. In his recent exhibition at the Beirut Art Center, the installation Years of the Shining Face: You Were Right, O Heart (2025) became one such space, surrounded by mirrors—a symbol of truth. In his performance Laughing on the River, Your Eyes Drown in Tears (2023)19 too, multiple works act as scenic elements relating to the text being read; for example, the series River Papers (2024) is printed on fragile carbon paper on which the artist copied the epitaph from his father’s grave in southern Lebanon. Each of these unique pieces reveals a different detail of the stone. The aforementioned disappearance of language here becomes physical, because, on this support, annotations and interpretations will fade away over time. Carbon paper is commonly used by scholars and anthologists of Arabic literature—as was Nassereddine’s father—to annotate and comment on books, without having to do it directly on the pages. There is something akin to a linguistic archeology in the artist’s gesture, one of rediscovery and interpretation in a different time and space. The baconstant shifting between quotes and his own words blurs the temporality of a language oscillating between the promise of preservation and the fragility of interpretation.

The performance also takes place around the piece A Few Decent Ways to Drown (2022), a marble fountain of lobed circular shape also covered with carbon paper on which the sun imprinted marks, like the reflection of water in a fountain. In the heart of a city, people gather around a fountain to cool down and tell stories. Tongues loosen there. This is what Nassereddine calls an unstable monument, around which chatter unfolds, a space that allows spoken languages to exist despite their ephemerality, revealing narratives from minority and marginal voices. It also reminds me of the first line of the poem “Grandir et devenir poète au Liban” (Growing up and becoming a poet in Lebanon) by Etel Adnan (1925–2021). “My oldest memory—the first object in my personal archeology—is a round stone fountain, low and carved into what I now think was limestone. And that fountain was empty.”21

When I told Nassereddine about this thematic similarity of the fountain, he answered that he did not know about the beginning of Adnan’s poem. Beyond their homage to classic Arabic poetry, with the metaphor of water in its abundance and scarcity, both artists-poets act, I think, within what Adnan calls “counter-profession,” meaning the fact, as explained by writer and translator Vincent Broqua, that her work goes beyond words by drawing from a performative, sonic aspect, going beyond the frame of the poetry field.22 This “counter-profession” is also evident in Nassereddine’s work, which combines visual art, music, and performance—all fields in which language is a discursive force.

At the center of this reconstituted stage, in the dark, facing the audience, Nassereddine recites his text in Arabic from memory, which is simultaneously being translated into English on a screen. The lines of pre-Islamic poet Imru’ al-Qais appear in a soundtrack alongside these of singer Mona Maraachli (1958–2016), singing, “لك شوقة عندنا ... يللي انتَ مننا” (“We miss your presence among us, you who are one of us.”) The voice reciting from memory highlights the fragility of language throughout time. The passage between languages creates a continuity between written and spoken forms of ancient poetry and translation as a form of interpretation. At some point during the performance, Nassereddine asks “Is this the same sun that used to grace the eyes of this pre-Islamic knight?”—that same sun which also graces the poets and artists of today’s world. “The subjects discussed by poets are, all in all, the same discussed by singers of today and yesterday”23—only the language, the way they are communicated differs. In his essay “The Poet,” twentieth-century essayist Ralph Waldo Emerson writes “The poets made all the words, and therefore language is the archives of history, and, if we must say it, a sort of tomb of the muses.”24 In front of Nassereddine’s work, language becomes a way to describe both the unspeakable and hope. Poetic metaphors are vessels for lessons from the past and carriers of collective imagined futures.

To Those You Love or Those Who Stab You, Who Make You Smile or Tremble25

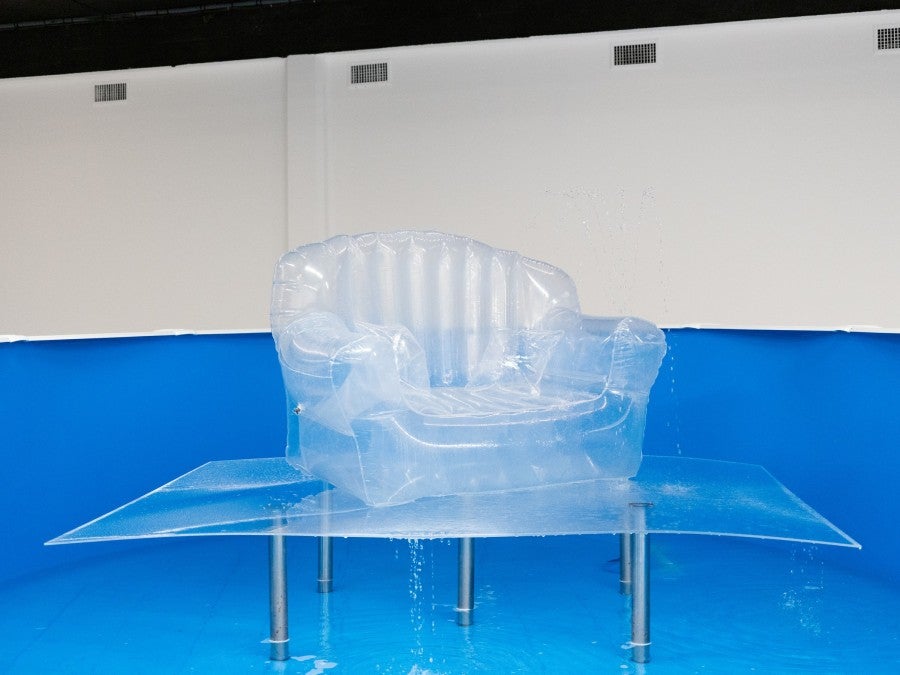

Artist Mégane Brauer’s exhibition Les Rois du monde (Kings of the world), which took place at the Musée d'Art Contemporain (MAC) in Marseille in 2024–25, also included a fountain. Built in an above-ground swimming pool shaped like a figure eight, at the center of which stood an inflatable armchair, the fountain is called Ça va déborder (It’s about to overflow, 2024). Water recirculated in a closed system, creating a constant lapping, a kind of decorative soundtrack with which household items formed a scene appealing to various collective imaginaries: both the forced holidays at home and that of the seat, as a symbol of power and domination.

Brauer describes her process when working on her pieces, and the increasing scale they take: “It starts very small, then it takes up space, like invasive plants that then complete the story.”26 Each of them is a fragment of a broken story, put back together for the first time in the space of the Marseille museum. They are chapters, like a novel graced with a new plot. Most of the time her texts are shown near each piece like clues offered to the audience. Reading them, we notice their fragmented structure shaped by generously punctuated brief sentences, which creates a shortness of breath in the reader, revealing the urgency of a language for remembering spoken word, something that eludes the archival and also most writing. Her texts are sometimes performed, read with the audience in the space, but collective reading is a recent practice in her work.

In Marseille, the text Cry me a river, was hung horizontally along a wall on multiple A4-sized sheets of paper. It locates the artworks within the exhibition, themselves starting points for the emergence of memories that viewers delve into: those of a generation, of the early 2000, and its abundance of musicals—the title of the exhibition is also a reference to Gérard Presgurvic’s musical Roméo et Juliette (2001). This was the beginning of online messaging, Skyblogging, and text messages in which users co-created, through imitation and mimicking, a language which has transformed our ways of communicating to this day. Codes were created, used to recognize each other as friends and allies, or, conversely, to distinguish enemies. The name of the main character in the story is “S,” imagined by Brauer, is reminiscent of the word hess (misery), transformed from the Arabic hessd, which means “nefarious intents.” What is nefarious here are words which exclude and wound, the words of an administrative system—in Brauer’s story, that is the system of debt collectors who knock on S’s door on a summer day.

Brauer speaks of the importance of intimacy when writing her texts. Specifically the intimate language which can too quickly be categorized as slang, the kind that is sometimes vague when we’re unsure of our words, the one that is in our thoughts before being exposed and vulnerable. Spelling mistakes and grammatical errors are deliberately ignored in Brauer’s texts: it’s a way to elude control and to allow her writing to free itself from restrictive and normative structures. In an interview, writer Chris Kraus described the importance of keeping a part of reality in fictional characters, their pathologies and flaws: “I’ve always thought the job of fiction is to do just that, but people today are so squeamish about reality.”27 There is something almost obscene about using spoken words to talk about the reality that some are living daily, especially when that reality is one of struggle and hard labour. The characters in Brauer’s autofictions find emancipation in language, away from the false hopes of happy endings promised in fiction. They exist with their reality, without anything hiding their increasing precariousness, a condition faced by redundant or demoted workers.

The clash between the economy of survival and systems of domination is actually a reoccurring subject for Brauer, who deconstructs power dynamics to reveal their most vicious sides in the social system. This is evident, for example, in her installation À nos deter‘ (To our grit, 2020), where buckets filled with foamy water are placed on Styrofoam podiums next to Crocs-style work shoes, bottles of detergent, mops, and brooms. The title draws on the shortened version of a word commonly used to amplify someone’s determination and also plays on the similarity of the words détergent and determiné (detergent, determined). In this piece, Brauer describes the work conditions of hospital staff—which included her mother, and mine—using a strong chemical cleaner smell as her backdrop.

Words usually associated with marginalization are habilitated by a system of recognition. The series of acrylic paintings on tea towels “Pour celleux” (For the ones, 2021–23) speak to viewers who might recognize themselves in the messages: For the ones, to the ones who die from living there (2021–22), For the ones who have been told it’s better than nothing (2022), and For the ones, to the ones who have been told to wash their children with bleach (2021–22), among others. Titles become enigmas expressing only established knowledge: what matters is identifying the reference rather than having the ability to decipher it. In fact, the title of each one of Brauer’s works indicates its subject so that its message cannot be manipulated. The goal here being to avoid any attempt at categorizing, appropriating, or speaking over in an era that sees certain codes of language being appropriated in marketing practices, just like in the ChatGPT machine. This might be about identifying the failure of a common language, the one that persists in a domination both symbolic and real.

The linguistic prism through which a story is told depends on one’s perspective, the language they’ll understand from it, that speaks in a “familiar” register, which could be perceived as inappropriate to some or incite a feeling of proximity in others. The stories Brauer writes address a universal subject known to all, like a fairytale, these stories passed on orally that form an important part of our collective memory. Each of us would have our own version of it, hence the text format of these works that resemble scripts the artist could have left to readers passing through her exhibitions, who could project their own memories and struggles onto it. “One doesn’t need to be a sociologist to acknowledge that the cryptographic aim of argot is a means of collective defense by the group; nor to be poet, in order to feel the creative and ludic aspect of this language” says writer Alice Becker-Ho.28 We simply have to accept that we cannot understand everything, that there are spaces in which the use of a language has to stay closed to some as a way to identify each other and protect each other from the potential attacks of language.

Talking about language using one’s own

Talking about language using one’s own inevitably adds a biased vision of the exhaustive nature of a subject like this one. The works of Bouchouchi, Brauer, Cheffi, Gokceyan, and Nassereddine all engage with languages outside of the sole artistic register: they are rooted in daily gestures of positioning, where language becomes a tool for resistance, self-affirmation, and even reinvention of speech.

During my research, I discovered the work of Italian poet, activist, and writer Patrizia Vicinelli (1943–1991), which I found inspiring in tracing a genealogy of plurilingualism in performance and graphic design in France. Her multilingual works in Italian, French, and English weave together poetry and plurilingual graphic experimentations, deconstructing language and offering a particularly inspiring way to see its political role, as an instrument of exclusion and normalization. In 1963, she was already writing “our alphabet has so few letters that I’m feeling ashamed.”29 Talking today about the use of language—at a time when language, neutralized and separated from its ability to act on reality, loses its illocutionary power—joins the preoccupations with social and economic mutations Vicinelli already raised at the time, calling for a plural and inclusive language in Italian society.

Language, as well as its examination in visual art, is not a new theme. What changes is that it is now approached from a much freer perspective, taking into consideration the emotions, the intimate space of each of us, and the conditions under which it is transmitted. The program I led for four years at Pickle Bar with my colleague Anastasia Marukhina explored language in its capacity for transformation, hybridity, and resistance—until it could offer new ways of being. Through this work, I understood the increasing place language was taking in the visual arts. We could talk of a “discursive turn,” mobilizing even those for whom language is not a research focus. Nowadays it is unusual not to plan a mediation program, a space for exchange, conversation, and debate as part of an exhibition or a performance. Be it in an artist talk or an exhibition text, language, and its textual forms, shape discourses. It has become an essential tool for situating and affirming oneself, and eventually existing, by following the subversive courses it offers, embracing linguistic diversity as forms of solidarity in the face of the systems living within a language and the constraints haunting it.

Translated from French by Salomé Mercier, copy-edited by Orit Gat

Co-founded in 2020 with curator Anastasia Marukhina and artists Slavs and Tatars, Pickle Bar is a non-profit project space located in Berlin-Moabit that focuses on performative and discursive formats.

Translator’s note: to maintain this distinction in the text, langue has been translated to language, whereas langage is almost always translated to “use of language.”

Jean Genet, Miracle de la rose (Paris: Flammarion, Collection Folio, 1980), 90.

رَبِّ اشْرَحْ لِي صَدْرِي* وَيَسِّرْ لِي أَمْرِي* وَاحْلُلْ عُقْدَةً مِّن لِّسَانِي * يَفْقَهُوا قَوْلِي (“Lord! Open up my chest, and ease my task for me! And untie a knot from my tongue, so that they may understand my words.” Surah Taha, verses 25–28.)

Nassima Mekaoui, “La domesticité coloniale en Algérie: la ‘fatma’, une ‘bonne de papier’ indigène au XXème siècle,” Le carnet de l’IRMC, issue 18 (September–December, 2016), http://irmc.hypotheses.org/2010.

Judith Butler, Excitable Speech: A Politics of the Performative (London and New York: Routledge, 1997), 2.

Excerpt from performance Steal, Steel, Still Fatma, Pickle Bar, 2024.

PNL, “au DD”, Deux Frères (QLF Records, 2019).

The concept of “linguistic imaginaries” refers to the set of representations and beliefs that a society or person associates with a language or a way of speaking. In her lecture-performance, Cheffi lists various languages, including “Breton, Alsatian with Pulaar, Arabic, Soninke, Kabyle, Romani, slang composed of words taken from these same languages.”

The work was produced by TBA21-Academy, TBA21 Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary Collection.

See https://kadist.org/program/triple-s-by-fatma-cheffi/.

“The networks in which poor images circulate thus constitute both a platform for a fragile new common interest and a battle ground for commercial and national agendas.” Hito Steyerl, “In Defense of the Poor Image,” e-flux journal #10 (November 2009), https://www.e-flux.com/journal/10/61362/in-defense-of-the-poor-image.

Cécile Canut, Provincialiser la langue, langage et colonialisme (Paris: Éditions Amsterdam, 2021).

“It is important to make a distinction between plurilingualism, which denotes an individual’s ability to speak multiple languages and multilingualism, which refers to the coexistence of multiple languages within the same space or community.” Lucas Da Silva, “Multilinguisme et plurilinguisme dans l'Union européenne,” Toute l’Europe (February 16, 2022), https://www.touteleurope.eu/societe/multilinguisme-et-plurilinguisme-dans-l-union-europeenne/

Theodor W. Adorno, Notes to Literature (New York: Columbia University Press, 1958), 106.

Emilio Sciarrino, Le Plurilinguisme en littérature. Le cas italien (Paris: Éditions des archives contemporaines, 2016), 62.

“Qu'est-ce que l'easy Arabic ou arabizi?,” Vous avez dit arabe? Un webdoc de l'Institut du monde arabe, see https://vous-avez-dit-arabe.webdoc.imarabe.org/langue-ecriture/l-evolution-de-la-langue-arabe/easy-arabic-ou-arabizi.

These are two versions of Armenian: western Armenian is spoken by diasporas from the Ottoman Empire, whereas Eastern Armenian is mainly used in Armenia and in the Republic of Armenia. Sonorities and words vary, in part because of reforms imposed during the Soviet Union.

This performance was produced by the Jameel Art Center (2023) and performed at Pickle Bar, Berlin (2024).

See http://husseinnassereddine.com/works/few-decent-ways-drown.

Etel Adnan, Grandir et devenir poète au Liban (Caen: L’Échoppe, 2019), 5.

Vincent Broqua, “La Contre-profession, sur les poèmes et l’art visuel d’Etel Adnan et de Liliane Giraudon,” Critique d’art, issue 62 (Spring/Summer 2024), http://journals.openedition.org/critiquedart/114452.

Conversation between the author and artist Hussein Nassereddine, April 1, 2025.

Quoted by Daniel Heller-Roazen, Echolalies. Essai sur l’oubli des langues (Paris: Editions du Seuil, 2005), 79.

“À ceux qu’t’aimes ou ceux qui t’surinent, qui t’font sourire ou trembler” Mafia K’1 Fry, Pour ceux, La Cerise sur le ghetto, 2003.

Conversation between the author and artist Megan Brauer, April 18, 2025.

Gary Indiana and Chris Kraus, “Autofiction and art world fuckery,” Interview (April 12, 2023), https://www.interviewmagazine.com/culture/gary-indiana-and-chris-kraus-on-autofiction-and-art-world-fuckery.

Alice Becker-Ho, Les Princes du Jargon, quoted in Keith Sanborn, “All the King’s Horses and all the King’s Men,” Edson Barrus e yann beauvais, bcubico (São Paulo: .txt texto de cinema, 2022), 392.

Patrizia Vicinelli, “Untitled” [1963], à, a, A (Milan: Lerici Editore, 1967).