It is an unusually warm June week when I travel by train from Paris to Lens. The small town in the northwest of France was an important coal-mining centre until the last mine closed in 1986. Today, it is the Louvre-Lens that puts this place on the cultural map. Although a visit to the museum has been on my list for a while, it is not the purpose of my trip. I am on my way to meet the artist Benoît Piéron (*1983, FR), who currently lives and works in Lens as part of a one-year residency programme.

As soon as I arrive, I am confronted with a large grey gate that blocks any view into the front yard. I ring the bell and it takes a little while before Benoît Piéron opens a smaller passageway through the gate. Shyly but welcomingly, he greets me and ushers me inside, into the freestanding house that was formerly a presbytery, he tells me. It is the type of house one mostly finds in the province. With its symmetrical façade marked by tall windows and completely surrounded by a lush garden, it conveys a modest grandness.

Inside the house, our conversation takes off. This studio visit is a kind of blind date as we have never met in person before. We talk about his many projects in 2023, including the group show Exposed at Palais de Tokyo, the Liverpool Biennial, his solo exhibition at Chisenhale Gallery, and the Pinault artist residency in Lens.

It is not long before Piéron tells me about how he was born with meningitis and got diagnosed with leukaemia at the age of three. In the 1970s and 80s in France, nearly 5,000 people needing blood transfusion were infected with HIV and hepatitis viruses through the use of contaminated blood products. Piéron was one of them, but unlike many others, he did not become seropositive. A couple of years ago, he was diagnosed with cancer. This series of events means he has spent a large part of his life from childhood onwards in hospitals, clinics and waiting rooms, to such an extent that these spaces have become second homes. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the experience of spending so much time in these spaces has shaped his perception of life and heavily informs his work. As we sit and talk about this particular childhood experience, Piéron says he thinks Monique is awake and ready to meet me.

Monique and beds

Monique Wittig creates the possibility of more layered existences of bodies in society (...) and this has been an ongoing source of inspiration for Piéron.

In the living room, the stuffed toy-bat Monique is resting on the coffee table, timidly holding her pastel-coloured wings close to her body. The bat as life companion, as formulated by Piéron himself, has always been by his side. He continues to tell me about the days and nights spent in hospital as a child, where the nights were often sleepless due to his health issues and the medication. In these moments between wakefulness and sleep, within the hospital setting that contrasts so sharply with a regular child’s bedroom at home, his imagination would run wild.

The colourful-companion-cum-materialised-imaginary-friend is named after the French author, philosopher and feminist theorist Monique Wittig (1935-2003), who attempted to dismember the body through words, to open up new space for corporeal possibilities.1 As such, Wittig creates the possibility of more layered existences of bodies in society, specifically female bodies in a patriarchal system, and this has been an ongoing source of inspiration for Piéron. However, another connection between Piéron and Wittig’s work crosses my mind. Her 1964 book The Opoponax is about children undergoing typical childhood experiences like a first school day or first romance.2 In this breakthrough novel Wittig addresses the protagonist with “you,” which gives the novel a direct tone, as if talking to and about a past self that is connected to a larger whole. Together with its fragmented anachronistic story line, the writing style stresses the non-linearity of memory—how memories of the past still influence the present and how new memories may also influence other, older memories. The significant amount of time Piéron spent in hospitals has had a lasting effect on his perception of life. Memories of these childhood experiences would re-emerge later in his life, and he went on to render them visible and palpable through his extensive body of work.

On the table next to the toy-bat Monique lays a French translation of The Little Vampire Takes a Trip, a book from Angela Sommer-Bodenburg’s famous series first published in Germany in 1982. The series revolves around a friendship between the nocturnal vampire child Rüdiger and a young diurnal human named Anton. Piéron identifies with the living conditions of the little vampire, drawing similarities with his own childhood experience of living in a parallel temporality of hospitals away from the family home, often lying awake or half asleep at night while many other children sleep, dream, think, or hallucinate as the mind does when it is in a liminal state. Since vampires are often considered analogous with bats, it seems only natural that his life companion Monique should take the form of the nocturnal flying animal.

Piéron tells me about another reference that shapes his thinking around the power of the imagination when circumstances force you into a confined space, namely the 1794 book Voyage autour de ma chambre by Xavier de Maistre. In the style of a grand travel narrative, de Maistre vividly describes the journey he undertook within his room when he was under a six-week house arrest. During this time, he observed all the details of the pieces of furniture and other elements in a specific room closely, moving back and forth between them. The story depicts the survival mechanisms of the creative imaginative mind.

Piéron reflects spatially on these moments in Le Lit (2011), which consists of—as the French title makes obvious—a bed. It, however, is not an ordinary bed, and definitely not one you might find in a hospital. The elevated tent-like installation is made with patterned silk fabrics, and the vertical lines of the four-poster shape are made of spools of thread, horizontally connected with colourful bunting and strings of light. On the headboard’s small shelf stands a bread toaster, two cups and an enema. On top of the bed is a dream catcher made of a red bodysuit in silk chiffon, and on each long side of the mattress is a gutter most likely alluding to the discharge of rain, sweat, faeces and nightmares.

Le Lit is an aesthetic manifestation referencing the wide range of activities connected to the space we call bed: from deep sleep to erotic dreams or sex, from a revitalising nap to being bed-bound due to illness. The bed as a site has become so central in Piéron’s life specifically, and is generally thought of as a site where experiences are processed and transformed into memories to virtually anyone, regardless of age, class, race, cultural background, geographic location or time. Thus, on one hand, a bed is utterly mundane, and on the other, it is a site where the imagining mind magically functions at full power.

Monique’s peers and the celestial

Piéron places the focus on welcoming a new illness, and a transition to a new state, in which something, the illness, will grow and flourish.

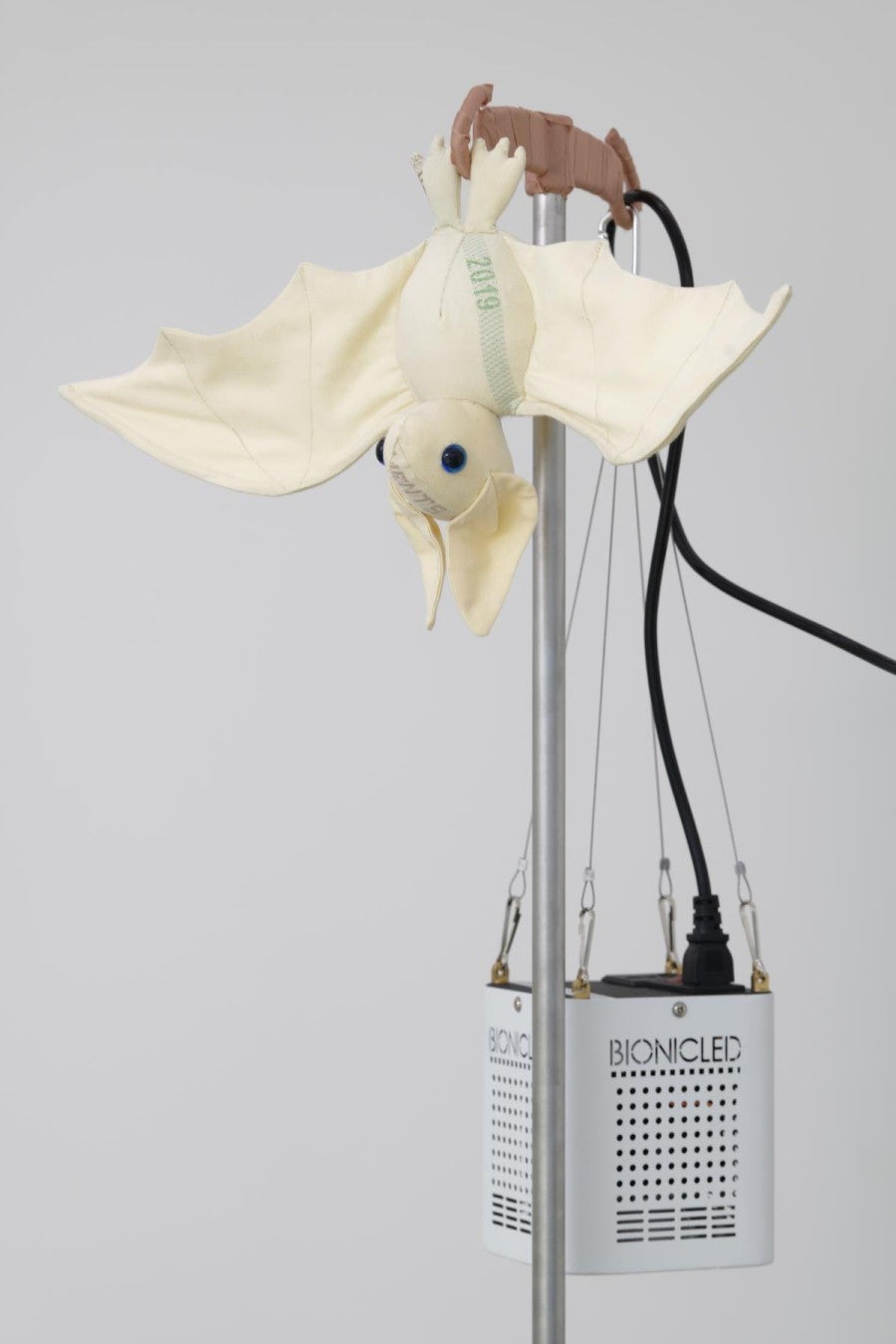

Now that I have been introduced to Monique, Piéron and I continue our conversation. As we look through his portfolio again, I realise that there are more bats to be found within his installations. They animate the works like spirit animals, as they hover over a space, like in maybepole (2022), or gather together as a group of friends, like in Peluche Psychopompe (2022). The maybepole work is a reference to the maypole, a tall-erected pole found in many Germanic-European cultures. Although it is widely used, its origins remain unknown. Erected in May or June if not permanently installed, the pole is activated to celebrate the return of summer and the growth of new vegetation.3 It symbolises the transition into a new, blossoming phase. Hesitation is introduced by the artist in the title of his work, reflecting the uncertainty one continues to live with after being diagnosed with a long-term illness. The work was presented as part of Piéron’s exhibition Illness Shower (Galerie Sultana, Arles, 2022), the title of which is a word play on the term baby shower. Instead of celebrating the expected birth of a child, Piéron places the focus on welcoming a new illness, and a transition to a new state, in which something, the illness, will grow and flourish. The approach might come across as macabre, but, as Piéron explains, it is merely a personal coping mechanism stemming from his experiences of dealing with illness and life within a sphere connected to, but placed outside of, society.

Through the work’s hanging bunting, both the maybepole and Le Lit share a celestial focus. The pole of the first piece lacks the part that usually grounds it, namely the pole itself, and has a focus point above the standing visitor’s head. The installation makes the visitor’s gaze follow the ascending lines of the bunting to eventually reach a centred ring where the pastel-coloured bat is suspended. In the latter work, the visitor—although not allowed to actually crawl in—is invited to imagine themselves lying in the bed, looking up at the inside of the tent and at the four posters with its vertical and horizontal decoration. Following this line of thinking, both works have a tilted perspective to connect the space from the predominantly horizontal line of sight with the space that is above, where the ceiling and sky are, where we imagine dreams take place, and where heaven is supposed to be. Living with severe illnesses and a deteriorating body, Piéron has spent a considerable amount of time lying down to rest and recover, with his gaze focused on, for example, the inside of the tent and the ceiling. As a person for whom the vulnerability of the body is not unknown, this shift in perspective indicates that he is not only concerned with what is grounded around us, tangible and fathomable, but also that which is rather up in the air, intangible and more difficult to grasp, like thoughts, dreams, death and heaven.

As our conversation continues, we come to talk about the Socialist Patients’ Collective, founded by Wolfgang Huber in 1970 in West Germany as the Sozialistisches Patientenkollektiv or, in short, the SPK. The Marxist collective was founded to stimulate discussion about patients—predominantly psychiatric—and their position in society. The collective followed a Foucauldian line of thinking and stated that most illnesses were caused by capitalist society, which itself could be considered sick. For the SPK, the aim of conventional therapy was to make patients suitable for reintegration back into that society. According to its manifesto—for which Jean-Paul Sartre wrote the preface—one should seek to resist this form of therapeutic reintegration by using the illness as a weapon.4 Later, the political tone of the collective radicalised, resulting in lawsuits against its founder and several of its members and leading to its dissolution in 1972.5 Although Piéron does not support the extremist goals of the not uncontested collective, he is interested in the shift in perspective about how ill bodies are placed outside of the production mode of capitalist societies and within adjacent spaces that function in a parallel dimension. They become, in the words of Piéron, the ghosts, vampires or bats of society. This paradigm shift gives people dealing with illness back their agency, in contrast to a common marginalisation from the neoliberal sphere of production.

The others and the waiting room

As Peluche Psychopompe (2022) illustrates, neither Monique nor Piéron are alone in their experiences. He tells me that, throughout his childhood, he got to know many other children facing comparable situations. They too had to deal with related or different illnesses, spend a significant amount of time in medical settings, away from regular daily life, and often found themselves in the liminal state of waiting. The installation Le Rayon (2023) is a simple yet powerful reflection on this. Commissioned for the 2023 group exhibition Exposed at Palais de Tokyo, one encounters a pastel yellow hospital door with a small rectangular window, its glass frosted. The space behind the door is bright, the colour of the light shining through the window and the interstice between the bottom of the door and the ground changing slowly. From time to time, the shadow of a person walking closely past the door is cast onto the window and floor. The sonic layer consists of sounds that are neither unfamiliar nor directly identifiable, and refers to the silence of a hospital night.

He commemorates and celebrates those who have found themselves in peripheral hospital settings, which exist in continuous parallel to the public sphere.

However, the visitor cannot open the door. The impenetrability of the work forces the viewer to slow down and interrupts the flow of them—fully—seeing the artwork. Such an interruption relates to a level of slowness in certain artworks that can have an impact on the viewer, as argued by Mieke Bal.6 As a cultural and literary theorist and video artist, she has written extensively about alternative temporalities and the political power of time in art. According to Bal, political artworks require “durational looking,” and it is through this that their political potential emerges, because these kinds of pieces tend to move the visitor.7 Art becomes an interruption of routine, because it speaks to the senses. In the case of Le Rayon, one hears indistinct sounds, sees light changing and human shadows passing by, and feels the impossibility of accessing the space behind it. All this makes the interruption sense-able and allows the onlooker to feel in their bodies the disrupted flow of their visit to the exhibition.8 Thus, through a visceral artistic encounter, the political potential, or more specifically the awareness of politics, starts to emerge. The experience of Le Rayon is however not only relevant to those who have been severely ill. Everybody has been in a room at some point in their life where one would hear things happening outside, or off-screen, and simultaneously realise one could not participate because of being confined to the room.

In this way, Piéron speaks to the viewer’s individual memory. According to Bal, time is the motor of memory and memory is typically understood as a cultural, individual and social phenomenon. Indeed, all memories have an individual, social and cultural element, because the subjects that remember—i.e. any human being—are also participants in these three domains.9 Bal also references the historian Harry Harootunian’s Marxist conception of time by saying that the past is “depositing in every present its residual traces that embodied untimely temporalities”.10 With Le Rayon, Piéron renders these three layers palpable by tapping into a visitor's personal memory, which is also a social memory as it took hold in a confined space, with other people being in close proximity yet out of reach.

Traces of the past are present throughout Piéron’s works with fabric. The aforementioned pastel-coloured fabric used to make the stuffed bats is upcycled hospital fabric including bed sheets. After being thoroughly cleaned, the fabric is resold at the large French DIY chain store Leroy Merlin. Nevertheless, traces of bodily fluids may remain visible on the pieces of fabric. Piéron has used this material to create several works that often pay tribute to the ill and hospitalised, like in maybepole or Matelas de plage series (2022), the latter consisting of four patchwork mattresses hung from the wall as a soft monument for the bedridden. Besides being the default colours of such hospital sheets, the pastel shades also have less heroic connotations for Piéron, because of their in-between position in colour schemes.11 Taking all this into consideration, the artist’s use of this material as a base for multiple works gives the previous users an immediate yet spectral presence within the exhibition spaces. He commemorates and celebrates those who have found themselves in peripheral hospital settings, which exist in continuous parallel to the public sphere.

Derek Jarman, Albrecht Dürer and the garden

Through the beautifully green, unmown lawn of the garden, a small pathway leads us to the square dark-wood studio space with its large windows that establish a strong connection between inside and out. As the surroundings are impossible to ignore, Piéron and I start talking about the garden and his time at the residency, a two-hour train ride away from where he lives in Paris. An urbanite, he says he has never aspired to live in the countryside, but has found that it does have a soothing effect. We soon come to talk about the experimental filmmaker Derek Jarman (1942-1994), to whom he feels a connection. Jarman also struggled with ill health, and he found refuge from urban life in his Prospects Cottage in Dungeness in the UK from the mid 80’s until he passed away. A passionate gardener from childhood and having a renowned eye for colours and aesthetics, the garden became his terrain for artistic gardening experiments as well as a form of pharmacopoeia.12 Jarman’s cottage and Piéron’s temporary studio have visual similarities and function as a heterotopia for them.

Plants and gardening are an existential part of Piéron’s practice, as they bring the notion of care and intimacy and shift the attention from his own body to other living entities. In his work Monstera (2022), the eponymous plant is installed on a serum holder in a tar pot as a nod to the tar roof of Jarman’s cottage. Above the monstera hangs a stuffed toy bat, like an upside-down guardian angel, as well as a horticultural lamp as if referencing the dynamics of what author and environmental researcher Stacy Alaimo called transcorporeality. Alaimo argues that—while we humans possess a remarkable talent for mentally dwelling in other times and places—transcorporeality calls on us to consider our fleshy selves in the here and now, as substantially interconnected with the substances, systems and social forces that traverse us.13 We are constantly interchanging with our environments, as water, food, air and many invisible chemical substances travel through our bodies. Transcorporeality embeds us again in the deeply-altered material world, from which Western ideologies have detached human beings over time. These ideologies considered the resources of this world as inert, primarily intended for human use.14 It is inextricably connected to discourses on the Anthropocene epoch, in which natural and human forces have become intertwined as a result of centuries of human activity. By placing the plant in the exhibition space with artificial UV light, Piéron suggests his work does not deal with abstract, inert concepts, but physical bodies and living entities that are being affected and maintained by human-made resources and acts. The body thus becomes porous and is holistically considered as part of a larger whole, where natural and human-made elements intertwine and reciprocally influence one another.

Piéron’s main artistic focus is not death or ways of ending life, but rather life in all its endless forms.

In L’écritoire (writing table) (2023), a sense of potential danger, self-determination and apprehension permeates. On an old writing table, spray-painted with pastel-colours, Piéron pots a selection of plants and places horticultural lamps above them. The plants are accompanied by the bat Monique, who sits quietly with her wings closed on the edge of the table and appears calm and grounded. Next to the writing table, a sign warns the viewer that the combination of plants is poisonous. Disconcerting as it may seem, the work can be interpreted as a hint at the possibility of using the plants—and perhaps other substances not on display—to intoxicate oneself or others in the exhibition space. However, as Piéron explained to me, the work is a symbolic act to sow death and take care of it, as a way to keep it at bay. In the same vein as the SPK, he shows the agency one has—whether a patient or not—and brings us into proximity with suicide and death in order to dissolve their entrenched separation from life.

Thus, Piéron’s main artistic focus is not death or ways of ending life, but rather life in all its endless forms. For The Great Piece of Turf – After Albrecht Dürer (2020–ongoing), Piéron was inspired by the eponymous watercolour of Albrecht Dürer from 1503. The artwork’s perspective is ground level and creates a frontal view of various types of grasses and other meadow plants. It represents the vegetation as being equal to other, taller living entities, for example a human or a tree, and depicts the small plants as if they are too attempting to reach the sky. Through this perspective of the vegetation, a celestial focus is again apparent in Piéron's work.

For Piéron, plants combine growth and perpetual resistance, vigour and slowness. He draws inspiration from Francis Ponge's conception of grass as expressing the most elementary form of universal resurrection.15 For his project, the artist sourced the seeds of the vegetation depicted in the watercolour and recreated the ensemble in different arrangements. In 2020, he created the first iteration on his balcony. Another was created as part of an exhibition at Le Mat in Ancenis (2021) where he also gave a workshop on Jarman’s garden after which the participants received capsules filled with seeds from the plants found at Prospect Cottage.16 Although still premature during my visit, the last iteration has been flourishing in the garden in Lens. One does not normally get to see a plant growing and changing, one sees it has grown and changed. Through this slowness, on the one hand, the existence of alternative temporalities becomes visible. Yet, on the other, the work reveals processes of both cultivation and natural transformation that exemplify the notion of transcorporeality and the reciprocal relationship between natural and human-made existences.

My thoughts and me all over the place

After spending the night in Lens, visiting the Louvre-Lens together and having more conversations, I have to head back to Paris. Piéron and I say goodbye and thank one another for the fruitful and extensive exchange. I get into the taxi to the train station and wave goodbye one more time, and he disappears again behind the large grey gate. Confined, I sink back deeper into the car seat and give my thoughts free rein. I look back to the gate, a separation that I already felt upon arrival, but which after our long conversations concerning boundaries between the societal centres and peripheries, people in healthy conditions and people dealing with illnesses, becomes an even stronger metaphor of processes of in- and exclusion, and the existence of parallel temporalities.

By shifting focus and decelerating pace, Piéron interrupts the flow of everyday routines and critiques our fast-paced neoliberal capitalist society and its ignorance of people not always able to keep up with its stride, due to unstable physical conditions ranging from the short term to the chronic. Something like that will happen to many of us, somehow, somewhere along the line. Fortunately, as Piéron represents and makes palpable, we can find companionship in plants, bats, and vampires, as well as in the spirits of other people who found themselves in a similar situation in the past, those who are still in such a situation and those who always will be.

Elliot Evans, The Body in French Queer Thought from Wittig to Preciado: Queer Permeability. Gender and Sexuality (Abingdon: Routledge, 2020), 142 https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/232982668.pdf

Douglas Martin, “Monique Wittig, 67, Feminist Writer, Dies,” New York Times, January 12, 2003, www.nytimes.com/2003/01/12/nyregion/monique-wittig-67-feminist-writer-dies.html.

Ronald Hutton, Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), 233–235.

SPK, Jean-Paul Sartre, SPK - Aus der Krankheit eine Waffe machen. Eine Agitationsschrift des Sozialistischen Patientenkollektivs an der Universität Heidelberg, (Munich: Trikont Verlag, 1972), 15.

“1970-1971: Das Sozialistische Patientenkollektiv – Krankheit als Waffe?” Heidelberger Kunstverein, last accessed October 21, 2023, https://hdkv.de/en/leseraum/1970-1971-das-sozialistische-patientenkollektiv-krankheit-als-waffe/.

Mieke Bal, “Activating Temporalities: The Political Power of Artistic Time,” Open Cultural Studies, no 2 (2018): 84–89, https://doi.org/10.1515/culture-2018-0009.

Bal, “Activating,” 101.

Bal, “Activating,” 93.

Bal, “Activating,” 97–100.

Bal, “Activating,” 97.

Benoît Piéron, “Rencontre avec Benoît Piéron.” Uploaded on April 3, 2021 at Cité Internationale des Arts. Video, 01:01, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6f_DnYTKq30&t=114s and François Piron, Exposé.e.s - D'après Ce que le sida m'a fait d'Élisabeth Lebovici (Paris: Fonds Mercator & Palais de Tokyo, 2023), Page number lacking.

Derek Jarman, Derek Jarman's Garden (London: Thames & Hudson, 1995), 11–14.

Stacy Alaimo, “Transcorporeality: From Bodily Natures to the Immersive Arts of the Anthropocene,” in: Leonie Radine (ed.), HIER UND JETZT im Museum Ludwig 5: Transcorporealities (Cologne: Buchhandlung Walther König, 2020), 215.

Stacy Alaimo, “Transcorporeality,” in: Rosi Braidotti and Maria Hlavajova (ed.), Posthuman Glossary (London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018), 435–438.

Benoît Piéron, “The Great Piece of Turf – after Albrecht Dürer,” filmed April 2020 for Artaïs, Paris. Video, 01:47, https://vimeo.com/589302206.

“DUNGENESS’ SEED BOMB – Benoît Piéron,” Le Crédac, last accessed October 21, 2023, https://credac.fr/artistique/dead-souls-whisper-1986-1993/dungeness.