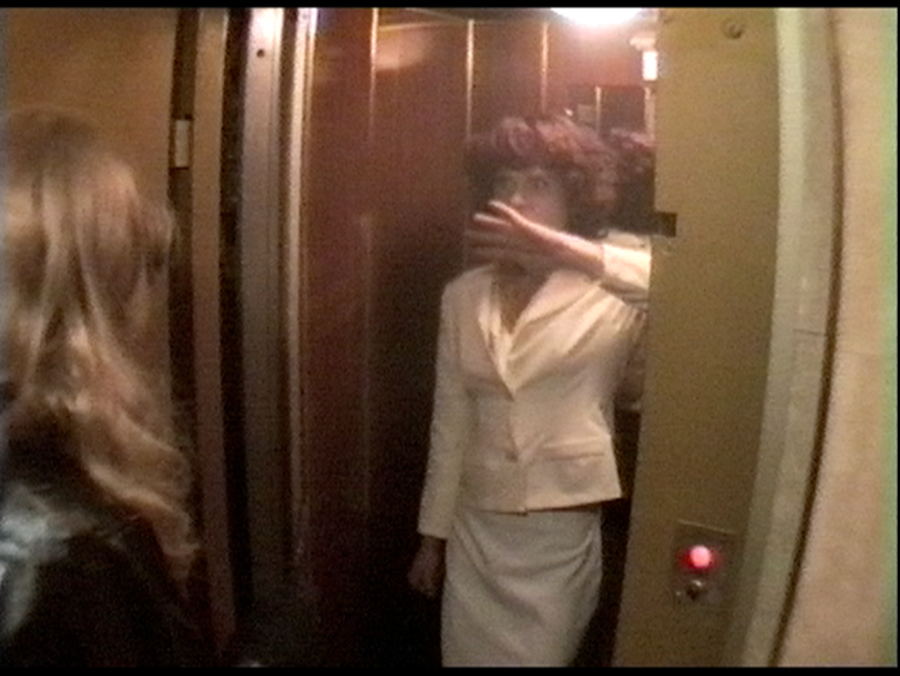

INT: ELEVATOR — NIGHT1

In closeup, a finger anxiously jabs button number six. It belongs to a fashionably dressed woman in a white blouse and cream trench coat, her dark red lipstick matching the color of her feathered hair. We see her through a fish-eye lens placed roughly where the button should be. She seems like she’s in a hurry. Then, the camera cuts to the elevator door as it slowly opens, and this time we see through her eyes: on the landing, a blonde woman in a black leather coat and gloves, her eyes shielded by dark glasses, approaches menacingly with a razor. Cut, cut, cut, cut—we switch abruptly back and forth between blond and redhead, foreshadowing the fatal blows. Finally, the door closes on them both, entombing killer and victim in a flying steel coffin.

But something is wrong here. It isn’t the presence of a homicidal maniac, nor the strangely impassive expressions on both women’s faces. It’s the fact that redhead and blonde, victim and slasher, are the same woman, which is to say, one man: the artist Brice Dellsperger, who plays both roles in drag. Cinephiles may recognize the scene in his Body Double 1 (1995) as the first murder in Brian De Palma’s 1980 thriller Dressed to Kill. In the spirit of a lip-sync, Dellsperger has even used the film’s original audio for his reenactment. De Palma’s preposterous melodrama is perfectly suited for the camp ventriloquism of a drag queen sashaying across a nightclub stage, and so we might be forgiven for thinking this is all an elaborate comedic routine. Dellsperger’s vaudevillian vamp makes us laugh until we suspect the joke may no longer be funny.

Brice Dellsperger, Body Double 1, 1995, with Brice Dellsperger, video SD 1.33:1, 0'48. Courtesy of the artist and Air de Paris

...victim and slasher, are the same woman, which is to say, one man: the artist Brice Dellsperger.

Metaphorical cracks start to show in the mirrors which line the interior walls of the elevator. The final frames of Dellsperger’s video, in which we see both women reflected together, could only have been possible with the aid of a body double standing in for one of the roles played by the actor-director—a trick that gives the work and ensuing series its name. In De Palma’s original, we see the lethal stab reflected in a convex mirror mounted in the upper corner of the carriage; in Dellsperger’s version, that mirror has become the camera. The artist quite literally sends us through the looking glass, a move he has repeated almost obsessively in the three decades since. His forty “Body Doubles”, painstaking recreations of scenes from his favorite movies with genders swapped and key details subtly altered, are self-reflexively turned in on themselves. That deceptively simple act of dress-up from 1995—like the very best art, a difficult thing made to seem easy—is part of a monumental undertaking the artist continues to this day.

As soon as Dellsperger’s vast archive of “Body Doubles” starts to cohere into a vision of the world, the reel sputters. Gender glitches. Identity malfunctions, its image repeated until rendered almost meaningless. We watch in bemused horror as the semiotics of cinema self-implode. Dellsperger reperforms scenes until they start to fall apart. Endless copies only prove that their sources are simulacra. As Judith Butler has argued, this is itself a hallmark of drag, which “constitutes the mundane way in which genders are appropriated, theatricalized, worn, and done; it implies that all gendering is a kind of impersonation and approximation.”2

Duly disguised, Dellsperger has snuck into the projectionist’s booth and swapped out all the parts for poorer ones, heightening our awareness of the medium’s technological illusionism. For those like him born in the twentieth century, film (along with TV) bears a singular responsibility for what Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick called our “subjectivation,” or the way we understand ourselves and others, such as our notions of masculine and feminine.3 Like Dellsperger’s sometimes confounding edits, those notions no longer make sense—if indeed they ever did. In Dellsperger’s hands, straight blockbuster cinema becomes an absurd, unworkable thing, much like heterosexuality itself. “If heterosexuality is an impossible imitation of itself, an imitation that performatively constitutes itself as the original,” Butler continues, “then the imitative parody of ‘heterosexuality’—when and where it exists in gay cultures—is always and only an imitation of an imitation, a copy of a copy, for which there is no original.”4

Perhaps nowhere is heterosexuality more grotesquely caricatured than in the films of Brian De Palma. Like his 1984 neo-noir satire Body Double, Dressed to Kill is a camp mash-up of the Alfred Hitchcock classics Psycho (1960) and Rear Window (1954), two films that conflate bloodlust with the cross-dressing and voyeurism at the heart of Dellsperger’s project. Men are aloof, women are lascivious, and a psycho-killer psychiatrist murders because they are both—or neither. De Palma pathologizes dysphoria by repeatedly presenting it to us in a mirror: while the surfaces of those mirrors are unbroken, the subjects we see in them are all cracked up. But in Dellsperger’s reenactments, which expose all their cracks, those subjects are made whole. Every role is inverted, and every actor, whether cisgender or gender-nonconforming, performs in drag. It’s all too fitting that the murder in Body Double 1 happens in a space that resembles a closet, that architecture of queer and trans subjectivation. A space which, according to Sedgwick, was constructed around the binaries of inside/out that attended to early twentieth-century stereotypes of “sexual inversion”.5 By killing himself—or rather, his double’s body double—Dellsperger had found a way to break free.

INT. CANNES — LATE 1970s

A film plays on a living room TV. “Why, I’m all dressed up and ready to fall in love!” purrs Babs Johnson, played by the actress and drag queen Divine. Her silver polka dot halter and angular brows are in soft focus, her movements strangely glitchy. The film is John Waters’ Pink Flamingos (1972), and Brice Dellsperger is enraptured. Of course, this isn’t my memory, nor is it precisely Dellsperger’s, who can’t recall the exact date he first saw Waters’ notorious film on a degraded bootleg VHS. Like the copy itself, the details are blurry. It may have been years later—but he remembers that the tape passed from one friend to another, its magnetic Mylar gradually losing luster. This was par for the course back then: “My generation was copying all the time”, he says6. Tapes recorded from the radio, illicit dupes of Cocteau Twins and Sisters of Mercy albums, were made and given as precious tokens. Copying something was a way of holding onto it.

Cannes may be a seasonal destination of the film industry, but it was hardly the center of the cultural universe during Dellsperger’s childhood there, and like any gay kid, the budding artist hoarded whatever media could offer him a vision of himself, however distorted—and by extension the promise of escape. He would annotate the TV Guide at his parents’ home to find the reruns of films and TV shows he liked, especially those with strong female leads. He loved the divas of Dynasty, Charlie’s Angels, and The Bionic Woman, and was fascinated that these series used wigged men as their stunt doubles7. How fabulous to don long blonde tresses and go flying through the air!

The first female TV action stars were a departure from the oppressive gender ideology of the postwar era, even if they were stereotypically feminine in appearance. Dellsperger describes this as the “washing machine of gender” where everything is always turning and nothing is ever “right-side up”; from an early age, he refused to get clean. Instead, through his practice, he became the women he idolized, using a medium of projected light to project himself onto the identities of others. “I’m trying to play with identification,” Dellsperger has said. “I believe that we identify with the characters that we like, up to the point of wanting to resemble them.”8 Indeed, as Butler notes, “identification and desire can coexist, and…their formulation in terms of mutually exclusive oppositions serves a heterosexual matrix.”9 As a very gay man knows, you can both want to be someone and want to fuck them at the same time.

...the incessant repetition (...) multiplies identity like a virus, one that inoculates those it infects.

According to José Esteban Muñoz, “identifying with an object, person, lifestyle, history, political ideology, religious orientation, and so on, means also simultaneously and partially counteridentifying, as well as only partially identifying, with different aspects of their social and psychic world.”10 Dellsperger’s Body Doubles recreate and reroute the identification he felt for those TV divas into something much more psychologically entangled. Rather, they recall James Baldwin’s having recognized himself as a young boy in Bette Davis, with her “pop-eyes popping”, when he first saw her in a movie matinee: “I was held…by the tense intelligence of the forehead, the disaster of the lips: and when she moved, she moved just like” a Black woman.11This famous white actress thousands of miles away from young Baldwin in real space and a million more in social standing was nonetheless proof that someone like him, which is to say an effeminate man with big eyes like hers, could command the stage. “I had discovered that my infirmity might not be my doom,” he writes; “my infirmity, or infirmities, might be forged into weapons.”12

Muñoz describes this move, which is both a projection onto the Other and a simultaneous turn away from them, as “disidentification”, and it is a crucial element of Dellsperger’s films. Disidentification “is a strategy that works on and against dominant ideology” such as gender: “Instead of buckling under the pressures of dominant ideology (identification, assimilation) or attempting to break free of its inescapable sphere (counteridentification, utopianism)” it “tries to transform a cultural logic from within”.13 More importantly, for Dellsperger, as “for Baldwin, disidentification is more than simply an interpretive turn or a psychic maneuver; it is…a survival strategy.”14

In 2017, more than two decades after his first Body Double, Dellsperger staged his own version of a scene from another Brian De Palma film, Carrie (1976), for Body Double 32. Rather than the memorable prom night bloodbath from the climax of the film, he chose a more innocuous scene from the beginning of the movie because he says it reminded him of getting bullied in the locker room as a young boy. By this point, Dellsperger had long stopped starring in all of his videos; the nonbinary actor Alex Wetter plays Carrie, along with all the other girls in the locker room—some nearly three dozen of them. With a soapy synthesizer score composed for the project by Didier Blasco, a collaborator on several Body Doubles, Dellsperger has drawn out De Palma’s tracking shot into an absurd, slow-motion titillation. When Carrie gets her period in the shower, we see her first reflected in the pipes; then, suddenly, she is everywhere. All the other girls, who previously had their own hair and makeup and personalities—if also identical faces—are now unmistakably Carrie too, their hands simultaneously covered in the same blood. “It’s a curse,” Dellsperger explains.15 A revenge spell? Perhaps: De Palma’s version is even harder to watch, as Carrie’s shame becomes an excuse for the other girls to torment her. Unlike her, they’ve all been through this before. But the incessant repetition of Body Double 32 goes further: it multiplies identity like a virus, one that inoculates those it infects. Revisiting a site of childhood trauma by reworking a camp classic from the artist’s youth, the video is an example of disidentification as survival strategy. It reminds us that because of—not in spite of—our differences, we are all essentially the same.

INT. NIGHTCLUB — 1995

Brice Dellsperger takes the stage. Which is to say the concrete floor and whitewashed wall of the open studios at Nice’s Villa Arson, repurposed for his very first live performance, Ladies and Gentlemen (1995). Dressed in a black corset, heels, stockings with garters, and a red feather boa, the artist begins a sultry strip-dance before his assembled classmates. Massive Attack’s “Be Thankful for What You’ve Got (feat. Tony Brian)” (1992) plays from a boombox. Dellsperger memorized the routine from the single’s music video, in which a woman performs an acrobatic strip-tease on the stage at Raymond Revuebar, a famous burlesque club in London’s Soho district. There’s already a subtle gender-bend to her lip-sync of Brian’s male falsetto, but in his re-performance, Dellsperger added a new twist, putting on his clothes instead of taking them off. The big reveal is an act of self-transformation, one that locates erotic pleasure in the social construction of gender rather than its biologically essentializing conception. It’s even more fitting that in the Massive Attack video, the star dancer performs in the set of an elevator, a cubicle the same shape and size as a closet—where Dellsperger would go on to film his very first Body Double later that year.

Dellsperger was a regular at the drag clubs in Nice before moving to Paris in 1995. “I was fascinated by these impersonators: the show is very frontal, meant to be seen from the front as an image, but the image has depth and relief,” he has said.16 In this sense, drag recalls what Erwin Panofsky famously observed of baroque art, such as Bernini’s Ecstasy of St. Teresa (1647-52): viewed frontally, sculptural tableaux are a kind of painting come to life.17 Perhaps the performances Dellsperger saw were statuary come to life—the animation of an impossible ideal, like Pygmalion’s Galatea. Exaggerated drag makeup certainly suggests an unachievable femininity. As for the performers themselves, Dellsperger admired their bravery: “I was fascinated with transformation,” he says. “I found it very daring…the biggest adventure, like going to the moon.”18

“For me, film is the result of a performance”

With his “Body Doubles”, begun shortly before he moved to Paris, Dellsperger sought to exert greater control on his work than could ever be possible in a live performance, though the spirit of performance remains in all of them. “For me, film is the result of a performance,” he has said. “In fact, the first videos in contemporary art were often recordings of performances.”19 This may be a reference to conceptual art practices of the 1960s and ‘70s, though Dellsperger’s work bears closer relation to the “Untitled Film Stills” of Cindy Sherman and the work of the 1980s Pictures Generation, whose appropriations critiqued the power of media in postmodern culture. Sherman used photography to recreate cinema’s mythologizing atmosphere; we know all of her women, whether or not we have seen them before.

In such a project, the characters are more real than the stage. “I conceive my work as a sum of artificialities—even if we are talking about performances taking place in the real world, they are then transposed into an imaginary world: what I call aesthetic flutter for my characters, which highlights a loss of reference points,” says Dellsperger. “Thus, my work contains the idea that the characters must come into tension with the artificial world into which they are inserted.”20 The artist’s avatars reclaim for themselves the power to define what is real and what is fake, flouting those who would set the terms of their identity. When they cut loose from the heteronormative world, the results can be dizzying.

Body Double 1 was the first of many De Palma homages. It was also not the last scene that Dellsperger would reconstruct from Dressed to Kill. Body Double 5 (1996) invokes the moment when Kate Miller loses all her reference points: while sitting before a portrait of a woman in an art museum, a mysterious, handsome man in dark sunglasses silently joins her. She smiles at him, but he doesn’t smile back; when he gets up, she follows him through a maddening labyrinth of Old Master paintings. Like so many of Dellsperger’s sources, this one is almost preposterously queer-coded, a cruising scene gone wrong. Art serves to literally scramble desire. But it’s difficult to recognize in Body Double 5 because the artist chose to re-perform it in a quiet corner of Disneyland Paris, that museum of the masses. And in the video, he cruises himself: we watch as two women with brown bobs, dressed in black suits—identical twins, digitally stitched together—sit side-by-side on a park bench. Their failure to recognize each other seems absurd; but Dellsperger’s video is a mirror which has transformed the self into an Other.

Body Double 5 also marked Dellsperger’s increasingly ambitious use of technology to duplicate and synchronize his videos. He was able to time his movements perfectly to the sounds of De Palma’s film by hiding a portable Hi8 player screening Dressed to Kill between his legs. The doubling of his image, accomplished with a simple split-screen in some shots and a more complicated post-production collage in others, presages the methods he would employ in subsequent “Body Doubles”. But technological precision, like the costuming of a drag queen, can only highlight its flaws the more it apes for perfection. And so too with Disneyland: until they are scheduled to perform, the actors in demented bodysuits who greet children at the “Happiest Place on Earth” are never allowed to be seen out of costume, but rather move about unseen behind the false facades of ancient architecture and snow-capped mountain ranges painted on wooden boards. Synchronization is a contractual requirement of the job. Like museums, theme parks strap us into their absorbing fictions. In them, gender is less a “washing-machine” than an endless roller-coaster ride.

The precise alignments of Dellsperger’s videos are no more important than the moments when they jump off the tracks. In 1997, he began experimenting with three-channel videos whose frames perform the same movie scene in sync with one another. In Body Double 8, three actors play Luke Skywalker and Princess Leia at the moment in Star Wars: Episode VI – Return of the Jedi (1983) when they discover they are siblings. In each channel, the actors have incestuously swapped roles. Once again, verisimilitude is not Dellsperger’s aim: even with the same clothing and makeup, these actors don’t resemble one another, and the cuts don’t always line up. This simultaneous multiplication serves to reinforce the notion that each copy has no original. These roles exceed the limits of their frames.

In his multi-channel videos of 1997, Dellsperger also began working with actors other than himself. He street-cast men and queens from Blueboy, a favorite gay club in Nice, and later met Sophie Lesné, whom he cast in Body Double 14 (1999)—a re-enactment of the campfire scene from queer classic My Own Private Idaho (1991)—at Le Pulp, a legendary lesbian club in Paris.21 He also initiated a decades-long collaboration with artist and punk-rock chanteuse Jean-Luc Verna, who in 2000 would star in Dellsperger’s most sweeping project to date: a painstaking recreation of all 102-minutes of Andrzej Zulawski’s L’important c’est d’aimer (That Most Important Thing: Love, 1975), in which Verna plays every single character. The choice of Zulawski is instructive, for the Polish emigre’s film follows a down-on-her-luck actress plucked from a soft-core porn shoot and cast in a stage play. The film’s opening scene breaks the fourth wall, inducing a Brechtian Verfremdungseffekt—that way of making the medium and its illusions suddenly seem strange. In Body Double (X), we watch as a dragged-up Verna comes horrified upon his own corpse, before a film crew of his clones intrude and reveal it all to be a performance for the camera. Dellsperger traced the bodies of every actor in the original film onto a transparency, laid atop a monitor, so he could tell Verna precisely where to stand. (In later Body Doubles, these positions would be mapped with gridded coordinates, like the choreography of a ballet.) All of these Vernas were then stitched together into a head-spinning composite, each haunted by a digital glow. Dellsperger’s film is not simply a representation of a representation, but rather a film about a film about a film, so referentially coiled it can send us in circles forever.

But then cinema is always a tangled affair. If it is continuous, that is because it loops back on itself. As much as they have grown in ambition, Dellsperger’s methods cycle in a similar way. Just as soon as he had completed the gargantuan task of digitally editing Body Double (X), the artist returned to his roots in performance, directing actors before a screen projection of David Lynch’s Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me (1992) for Body Double 17 (2001). Lynch’s actors have been edited out of the original frames, so the actors were free to perform under stage lights whose colored gels approximated the hues of the original production. There’s something deeply unsettling—Lynchian, perhaps—about the fact that Dellsperger has spirited Laura Palmer away and replaced her with a doppelganger. With its unique methods, Body Double 17 may be more realistic than other Dellsperger videos, but like the dark pools in Body Double (X), it is haunted by the graininess of its background image, as though Lynch’s film about a case of spiritual abduction has itself begun to disappear.

Until Body Double 21, Dellsperger always used the original sound from films to score his videos. In that work, a reaction of the bathtub suicide from Rules of Attraction, Harry Nilsson’s “Without You” (1971) from the original soundtrack has been distorted so it sounds submerged in bloody water. If Dellsperger’s precisely coordinated lip-syncs had “the ability to collapse the boundaries of self and other…suggesting a singularity between performing body and the voice of the track,”22 then his subsequent audio manipulations, which mimic but do not replicate the original soundtracks, underscore the difficulties of articulating one’s identity in any representational medium. What’s more, they often tease out subtext to perverse extremes.

In recent years, Dellsperger has collaborated with the director and composer Didier Blasco to create new scores for his videos, including Body Doubles 32, 35 and 36. On a practical level, this may have been a way of circumventing copyright issues, but it also invokes the long history of cinematic dubbing, common practice for foreign films and TV shows in France. We might consider Dellsperger’s films themselves to be dubs, rather than doubles—translations, not copies, which add just as much to their sources as they take from them. The gaps of meaning introduced by translation are also fundamental to the way cinema functions on a representational level. “Because the spectator and the actor are never in the same place at the same time, cinema is the story of missed encounters,” Kaja Silverman has argued. “Moreover, unlike theater, which employs real actors to depict fictional characters, film communicates its illusions through other illusions; it is doubly simulated, the representation of a representation.”23 In Dellsperger’s Body Doubles, there’s no telling where this hall of mirrors ends.

INT. DANCE STUDIO – DAY

Dellsperger’s videos (...) are not representations but deconstructions of the way identity functions in a world shaped by cinematic fictions.

A woman swings her head to the beat of the music, cracking her high ponytail like a whip. At first, we see only her head and shoulders, mirrored in the video’s adjacent channel. As the sequence continues and the camera begins to pan out, we realize the mirroring is more than just a post-production effect: this woman is in a dance studio with mirror-paneled walls where she—along with her students, who are also herself—are reflected in a kind of infinite regression. Dellsperger staged the campy aerobics class from James Bridges’ 1985 rom-dram Perfect over one arduous week at his alma mater, Villa Arson, for Body Double 36 (2019). Jean Biche dances every role; as in so many of Dellsperger’s videos, all the men in the room—including the film’s male lead, played by John Travolta—have become women. In his musical adaptation, Didier Blasco has given the scene’s original soundtrack, Whitney Houston’s “Shock Me (with Jermaine Jackson)”, a slightly manic, hyperpop feel. As it drags on more than twice the length of the original scene’s 4-minute run, we start to notice that not everything adds up: the mirrors in the studio don’t always reflect the bodies before them. The two mirrored channels are likewise not always the same. Repeatedly, Jean Biche’s lock-stepped avatars fall out of sync with one another, and even with their own reflections. If the mirror image has lost its fidelity to truth, then so, too, have the representations in Dellsperger’s cinema—a medium whose technological apparatus depends upon the use of such mirrors to reflect light.

When the work was installed at Villa Arson, both channels were projected onto a 17-meter screen atop a mirrored floor, placing viewers within a cinematic kaleidoscope. Pulsating bodies folded symmetrically around a central focal point, like endlessly contracting labia. The display suggested that both the interior and exterior architecture of cinema can serve to amplify its self-referential illusionism. Similarly, the dislocations in Dellsperger’s video remind us that we shouldn’t always believe what we see.

In this sense, Body Double 36 implodes its source material, folding those titular, athletically “perfect” bodies in on themselves. The video sends identity, or more precisely self-image, back through the mirror in which it was originally constituted. Lacan’s famous mirror stage, that crucial moment of childhood subjectivation when we learn to recognize our own reflections, is complicated by our identification with actors on the silver screen. We may know we’re not looking at ourselves in a film, but that doesn’t prevent us from imagining ourselves up there, living out all the same actions. That quality of cinema is what makes it such a powerful propaganda tool—and conversely, in Dellsperger’s work, such an effective mechanism of critique. As the Lacanian psychoanalyst and film theorist Christian Metz observed, cinema is a “chain of many mirrors” like “the human body, like a precision tool, like a social institution.”24 All three of these aspects come together in Dellsperger’s videos, only to subsequently fall apart. His works are not representations but deconstructions of the way identity functions in a world shaped by cinematic fictions.

Brice Dellsperger, Body Double 36, 2019, installation, double projection synchronized, film 2K, format, 2.39 letterbox, sound, 08 min. 58 sec. Courtesy the artist and Air de Paris, Romainville

Recently, mirrors have assumed an even more central role in Dellsperger’s videos, abandoning any pretense that their reworking of cinematic references are not also a reflection of the viewers themselves. In Dellsperger’s Body Double 39 (2024), three actors across three channels swap roles as the twin gynecologists and their lover in David Cronenberg’s Dead Ringers (1988), with the twins wearing eyeless, mirrored masks. As the channels fall in and out of sync with their audio track, the masks suck in all our attention, warping not just their surroundings but also the camera’s gaze. Dellsperger calls the mask a “black hole”, which seems fitting, not just for the way it structures the image but also the way it erases the actors’ expressions, key narrative indicators. If before, Dellsperger’s videos mostly cast the same actors as different characters, here different actors are presented as identical. The mask literalizes that process by which we project our shifting desires and (dis)identifications onto cinematic characters, momentarily collapsing the space between self and Other. As with all of Dellsperger’s work, meaning is quite literally in the eye of the beholder; by the same token, a young gay boy can see himself in the eyes of a female diva. This is cinema as a reflective void—one in which we may find ourselves and perform how we want to be.

Note to reader: the subtitles in this essay are formatted as scene introductions, also known as sluglines, in a film script. They were adapted from the script of Dressed to Kill (1980). “INT” here signifies “interior.”

Judith Butler, “Imitation and Gender Insubordination,” The Lesbian and Gay Studies Reader, ed. Henry Abelove, Michele Aina Barale, and David M. Halperin (New York: Routledge, 1993), 313.

Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, “Introduction: Axiomatic”, The Epistemology of the Closet (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990), 1-66.

Ibid, 314.

Ibid, 46.

Conversation with the artist, Paris, 12 March 2025.

Conversation with the artist, Paris, 14 March 2025.

Brice Dellsperger to Marie-France Rafael, Brice Dellsperger: On Gender Performance, 44.

Butler, 314.

José Esteban Muñoz, Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999), 8.

Ibid.

Ibid, 9.

Muñoz, 11.

Ibid, 18.

Conversation with the artist, Paris, 14 March 2025.

Brice Dellsperger to Marie-France Rafael, 22.

Erwin Panofsky, “What is Baroque?”, Three Essays on Style (Boston: MIT Press, 1997).

Conversation with the artist, Paris, 14 March 2025.

Brice Dellsperger to Marie-France Rafael, 26.

Ibid, 33.

Conversation with the artist, Paris, 14 March 2025.

Jacob Mallinson Bird, “Touching Synchrony: Drag Queens, Skins, and the Touch of the Heroine,” Ethnomusicology Review, 23 July 2017, https://ethnomusicologyreview.ucla.edu/content/touching-synchrony-drag-queens-skins-and-touch-heroine

Kaja Silverman, The Acoustic Mirror: The Female Voice in Psychoanalysis and Cinema (Theories of Representation and Difference) (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988), 3.

Christian Metz, The Imaginary Signifier: Psychoanalysis and the Cinema (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1982), 51.