To listen requires an attunement to sonic frequencies of affect and impact.1

Tina M. Campt

To hear sound politically is to hear the possibility of another world.2

Salomé Voegelin

In his 1550 work, De Subtilitate, Girolamo Cardano explores the intriguing ability to hear sounds not just through the ears but also through the teeth and bones. The Italian physician, mathematician, astrologer, and philosopher observed that a d/Deaf person could perceive sound when a stick or rod was placed between their teeth, allowing vibrations to reach the skull. He theorised that sound could travel through solid materials to the inner ear, bypassing both the outer and middle ear. While the complete anatomical explanation for vibratory conduction to the auditory nerve, which is the basis of bone conduction, came centuries later, Cardano’s insights laid the groundwork for future scientific developments.

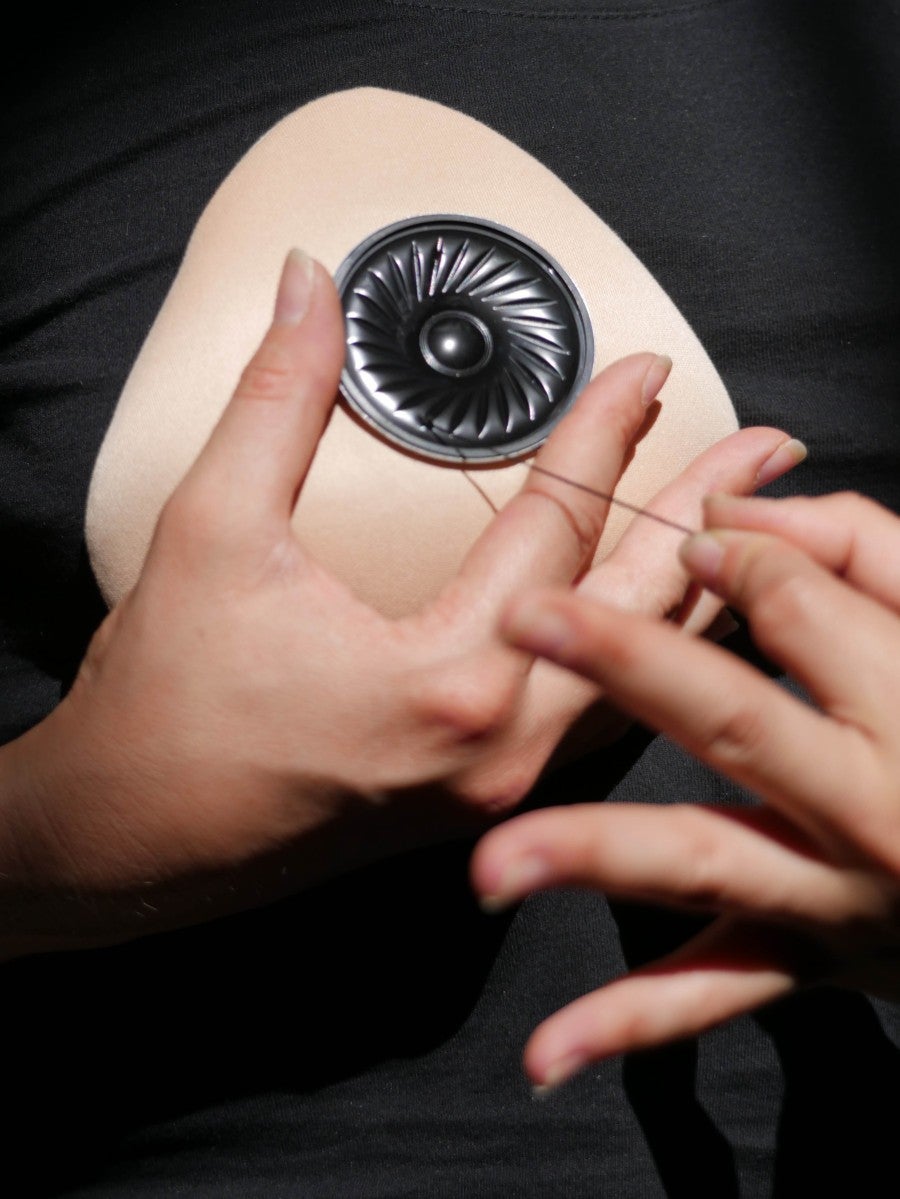

In Racine, Pistil (2024), a sound sculpture by Anne Le Troter (b. 1985, Saint-Étienne), the listener places a twig in their mouth. The other end of the twig is positioned directly on the end of a bent steel wire protected by bra cups that are folded to resemble flowers. The wires sprout from within an arrangement of dried plants and stainless-steel rods connected to a sound amplifier. The sound then travels through the metal steel—steadily and insistently—up through the twig and into the listener’s teeth, redistributing speech into the depths of the ear via bone conduction. This gesture—intimate, slightly absurd, and erotically charged—collapses the distance between hearing and the body, allowing the sound to become a mouthful experience and the listener to swallow the words they are hearing.

The language used by Le Troter is rich, tactile, and visceral, blending erotic discovery with botanical cycles, full of words that hum, drip, squish, or fracture.

Le Troter is by no means a scientist, but she is deeply attuned to how scientific protocols and technological developments shape the materiality of language—particularly spoken language as it circulates through institutional, corporate, and affective systems. Working across sound installation, performance, writing, and theatre, the Paris-based artist investigates how speech functions within architectures of power, intimacy, and abstraction. Racine, Pistil draws on the genres of audio pornography, sonic erotics, and ASMR—registers of auditory stimulation that would have likely astonished a figure like Girolamo Cardano. Its script, titled “La Pornoplante”, introduces a poetic metamorphosis of the narrator’s body, the artist, which begins to sprout a sex organ—a new, vegetal entity that blossoms late in life.

Swallowing someone else’s discourse may be the most sensual listening practice I’ve ever encountered in an exhibition space. This choreography of ingestion enacts what Le Troter describes as “consensual listening”: a mode of reception that foregrounds the listener’s agency while inviting them into a space of heightened vulnerability. Consent here is not merely procedural but affective—it involves a willingness to let another’s voice resonate inside one’s body, to host speech not only in the ear but in the mouth, the teeth, the bones. The act of listening becomes inseparable from touching, tasting, absorbing. By offering two different audio tracks—an erotic tale for adults and a metamorphosis fable for younger listeners—Le Troter structures a listening encounter as a shared, negotiated practice.

The botanical metaphor frames sexuality as a deeply embodied non-normative experience, tied to seasonal time and corporeal vitality. While the script chronicles the joyful, instinctual exploration of this newfound body part, this vitality is seasonal: as autumn arrives, her sex withers and falls off. She mourns this loss, contemplates decay, and as winter draws near, she reverts to the “Ministry of Solitude,” a fictional social service that provides standardised care aimed at fostering reconnection or rehabilitation. A stand-in for the medical-therapeutic-industrial complex, this institution reflects how prevailing systems reduce complex bodily transformations, transitions, and affective states into manageable symptoms while neglecting the poetic, the unquantifiable, and the erotic. As she explores other therapeutic options as alternatives to institutional care, she finds comfort in spring’s eventual arrival, hinting at a cyclical, generative temporality of the body. While she dreams of growing an even larger sex, “new and unshakeable”, evoking a kind of phallus decoupled from patriarchy, the sex organ is never gendered. Instead, it is a vegetal, transcorporeal experience—an intermediate life form, part human and part plant.

The language used by Le Troter is rich, tactile, and visceral, blending erotic discovery with botanical cycles, full of words that hum, drip, squish, or fracture. The script was written during a residency the artist did at the Bergerie Nationale de Rambouillet, a centre for agricultural research and innovation established by Louis XVI to enhance wool production and farming methods in France. During the nineteenth century, the Bergerie transitioned into an experimental farm, breeding sheep and, eventually, other livestock, becoming the first in France to implement assisted animal reproduction. For Le Troter, this historical context serves as a profound metaphor for sexuality within the medical-pharmaceutical framework, drawing parallels between animal control, human desire, and autonomy.

In “La Pornoplante,” the voice is not merely a tool for communication; it embodies flesh, form, resistance, seduction, and excess, articulated in writing and gutturally received by the listener. Le Troter approaches the voice not as a transparent carrier of meaning but as a tangible material—fragile, resilient, and expressively rich beyond mere semantics. Her sonic works frequently pause or reject verbal language to privilege other forms of communication (such as groans, silence, and chewing). There is a strong emphasis on how language and voice are inherently relational. Her works help foreground a poetics and politics of voice, not as an abstract symbol but as an inseparable, living remnant of the body, which is a mutable, politicised site.

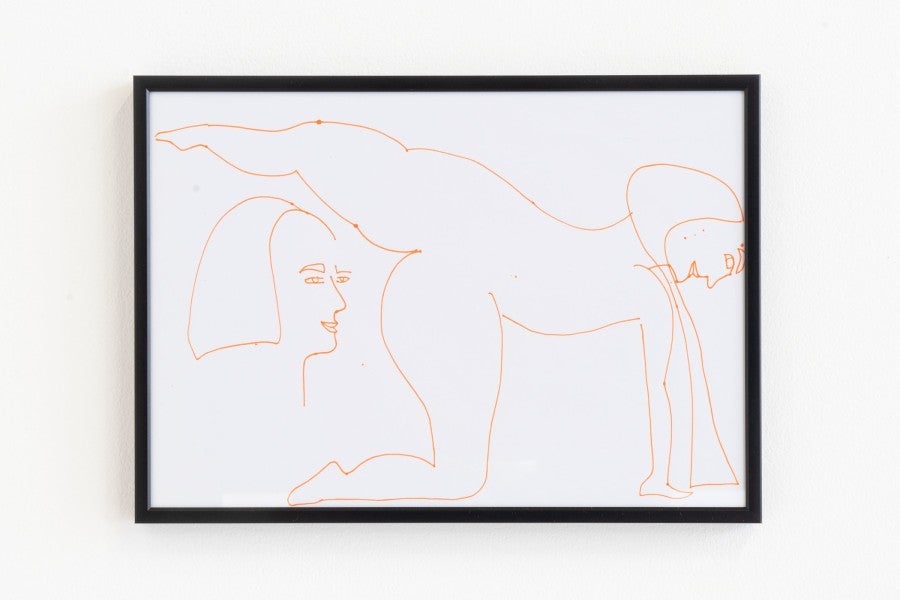

An earlier presentation of “La Pornoplante” (Chapitre 1/3) (2021) at Bétonsalon – Centre for Art and Research in Paris featured an audio piece that vibrated beneath the listener’s body, transmitted through audio cables woven into a seating structure—a bench fitted with small loudspeakers nestled inside folded bra cups, as if the sound source were pistils awaiting pollination. Her installations and sound sculptures often distribute voice across space and furniture, such as benches, cushions, and cables, turning language into an environmental vibration. Through carefully composed listening environments, she creates spaces where listening becomes a collective, embodied, and sometimes uncomfortable experience.

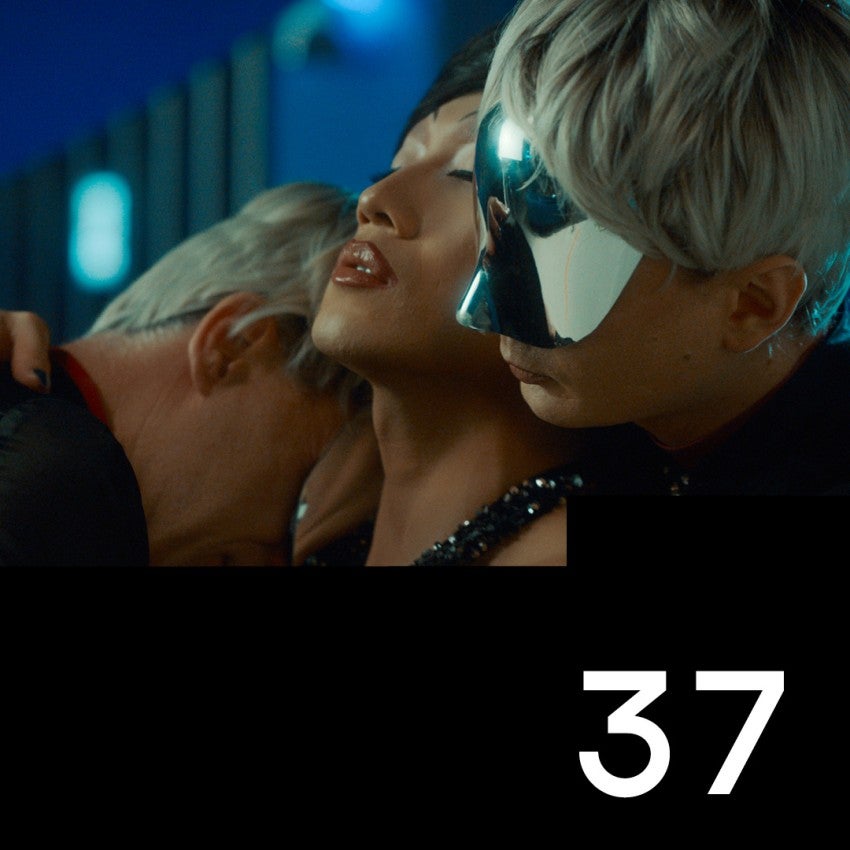

For instance, in Le Corps Living Room (2023), a group of individuals defy traditional notions of posture and productivity, transforming into furniture, such as chairs, tables, and candelabras, in a forest setting. They enact a form of resistance to capitalist logics of value through immobility, merging endurance with a sense of passivity via intimate sound-based rituals. The experience of “being a chair” represents both a physical and philosophical rejection of societal norms surrounding labour, visibility, and verbal engagement. Through humour, poetry, and grotesque imagery, they explore themes of utility, erotic objectification, and primal desire.

Presented in a scenography of audio cables, the sound sculpture features two glass plates fitted with transducers that vibrate to the piece's frequencies. Visitors touch the glass to feel the sound. Within these plates, Le Troter depicts two characters: one character is seen copulating with a house plant, while another merges erotically with a coffee table. In the script, another character envisions becoming a dog toy, “nibbled, licked, dribbling with saliva.” Their ultimate aspiration is to evolve into cherished objects that tread the fine line between love and destruction. Here, achieving a sessile state, akin to that of a plant, or adopting the stillness of furniture embodies a paradoxical form of agency.

The sound installation At Distance Speak, or Hold Your Tongue (2019) is set within the sterilised architecture of a sperm bank. En route to an exhibition, Le Troter encountered an employee who described, with procedural ease, the selection process for potential donors. On the company’s public-facing website, donor profiles are accompanied by recorded interviews in which men respond to softly scripted questions about their childhood, work, family—vignettes of intimacy framed for assessment. These recordings are punctuated by commentary from the clinic’s staff: “He is cute, handsome, funny…” Such casual affirmations, tender and transactional at once, amplify the dissonance at the core of the exchange.

For this fictional sound piece, Le Troter worked with actors to recreate the sampled voices alongside automated messages, and marketing-like descriptions based on the staff’s commentary. The language is repetitive, banal, and oddly poetic—filled with “And hum…”, corporate tones, and emotional sales pitches. Donors are described in fragmented ways: “sweet,” “fit,” “funny,” “gentle,” “sincere,” forming an absurdly looped sound object and composite of idealised masculinity. The piece critiques how language, especially commercial and reproductive discourse, commodifies intimacy, bodies, and emotion. On making this sound work, Le Troter explains,

“(…) I made a song based on 400 commentaries from the business’s employees, focusing on 400 sperm donors. The whole thing forms a sort of pre-adolescent nursery rhyme, naïve and intoxicating. (…) I dwelt on each of the anecdotes to create an aural love song, a nursery rhyme and a poem, focusing above all on the beauty of the act [of donating sperm].”3

First presented at the Contemporary Art Centre of Saint-Nazaire and later at the Centre Pompidou, the installation unfurls across a soft, clinically pink environment, staging a waiting room where bureaucratic care and sonic intimacy converge. The waiting benches are ribbed with kilometres of exposed audio cable, thread through the space like urethras, carrying a six-channel composition that hovers above visitors’ heads, enacting an architecture of disembodied utterance. Within this affective space, voices meant to reassure or inform unravel into absurdly over-articulated portraits of sperm donors, their emotional profiles rendered with ambivalence. Here, the sterile and the sentimental coalesce to reveal the uncanny heart of the reproductive apparatus: a manufactured intimacy—polished, looped, and strangely vacant promise of hope and possibility.

Using a similar spatial vocabulary, The Volunteers, pigment-medicine (2022) unfolds as a sonic reenactment that entangles the voices of Jean Cocteau, Josephine Baker, Max Beckmann to portray the 20th-century artist Louise Hervieu, who created the health record booklet used in France. In this audio piece, Le Troter reconstructs their exchanges and invites artists to lend their voices, reactivating their debates. Through a fictitious therapeutic protocol, they imagine to have donated parts of their bodies for pigment extraction. Together, they develop, through their conversations, the medical biography of a collective body based on the transtemporal experience of artworkers.

The novelty of the sound sculpture lies in the way the audio cables connect to welded steel forms poured directly into the gallery floor, shaped into erotically charged silhouettes—as if the building itself were exuding from its pores. By weaving together fragments of historical fiction, bureaucratic language, and testimonial registers, Le Troter constructed an immersive acoustic environment in which language circulates between archival residue, architectural excretions, and bodily intimacy. This polyphonic constellation shown at Bétonsalon embodies what Le Troter calls a “mild dramaturgy,” where the listener is left to navigate ambivalence rather than narrative closure.

Across these sonic pieces, Le Troter and collaborators (friends, AMSR artists, volunteers) build a universe where the body speaks in unexpected languages, exploring the unruly, excessive, and sonic dimensions of the voice. They defy functionalism, eroticise passivity, and transform the grotesque and intimate into tools for both poetic expression and political critique. These texts inhabit speculative worlds where becoming something else (plant, chair, dog toy) is both an escape and a form of resistance. As bell hooks reminds us, spaces of resistance—as locations of radical openness and possibility—are where a counter-language may emerge, and with it a “new location from which to articulate our sense of the world.”4

Vocality at the Edge of Meaning

In Le Troter’s practice, writing is not subordinated to thinking, nor does it function as a fixed repository of meaning.

Western philosophy has a long history of attending to what is said instead of how it is said. In For More than One Voice: Toward a Philosophy of Vocal Expression, Adriana Cavarero, an Italian feminist philosopher, critiques this philosophical tradition, particularly from Plato to Derrida, for privileging logos, or meaning, language, and rational discourse over phōnē, understood as voice, sound, and bodily presence.5 Cavarero insists the voice is never anonymous. Each human voice is uniquely tied to the person who emits it. Unlike written text or abstract language, the voice carries affect, presence, gender, and corporeality. Hearing someone’s voice is hearing them, their gender and corporeality—it is a revelation of who speaks, not just what is said.

Yet written text, too, can serve as a means of destabilizing the long-standing opposition between logos and phōnē. In Le Troter’s practice, writing is not subordinated to thinking, nor does it function as a fixed repository of meaning. Instead, it becomes a score, a porous script that anticipates its own sonic fracture. I understand the relationship between writing, uttering, and listening in her work as a challenge to the dominant philosophical privileging of logos — the notion of rational, semantic discourse — as well as Cavarero’s dualist approach.

This resistance is particularly legible through two conceptual lenses: first, via feminist semiotician and psychoanalyst Julia Kristeva’s theories of the semiotic chora, pre-linguistic vocality, and abjection, which foreground rhythm, affect, and the bodily residue of language beneath the symbolic order;6 and second, through Salomé Voegelin’s sonic ontology, which, while phenomenologically framed, similarly emphasises sound as material and temporal process — unfolding outside of language-as-sign system.7 Both frameworks offer crucial insight into Le Troter’s exploration of the voice as an embodied and affective field, where meaning is not transmitted but felt, disrupted, and remade.

Introduced in Kristeva’s book, Revolution in Poetic Language (1974), the semiotic chora—derived from the Greek word chōra, meaning receptacle or womb—is taken from Plato’s Timaeus and describes a pre-symbolic realm of drives, rhythms, and bodily intensities that precedes structured language, which she terms the symbolic order. The chora represents not language itself, but rather the physical foundation from which language ultimately arises. The semiotic, therefore (not to be mistaken for semiotics concerning sign systems), refers to sounds, silences, intonations, and physical expressions like moaning, sighing, humming, or babbling—commotions that convey meaning without signifying explicitly.

Anne Le Troter, La Pornoplante, Chapter One, excerpt, 2020. View of the opening of Good Service, Good Performance, at Magasin CNAC, Grenoble, March 15 – August 31, 2025. Activation of Anne Le Troter’s work, Plant Assistance, 2025. Courtesy Magasin CNAC. Photo: Pascale Cholette

In Le Troter’s work, panting, stuttering, muttering are loud. Her voice is deep, full, and rounded. For her, recording is a return to the intimacy of hearing a text in her mind while writing—a way of listening inward before sounding outward. Each audio piece holds two voices: the voice of the script and the voice that voices the script. As she told me in her studio in Paris, she is interested in assemblage, amalgamation, and in composing a portrait of someone not through image, but through her mouth—tongue shaping words, editing time. What emerges is a form of concrete poetry, one that resists legibility and disorganises the sonic markers of gender and class.

Voegelin, who treats the voice as something that does not necessarily speak but resonates, enacts, or unfolds, advocates for a kind of listening that precedes interpretation; a listening that does not aim to decode but to experience, inviting openness to uncertainty and ambiguity—an embodied, durational encounter rather than a semantic act. Vocality, in this sense, brings about subjectivity not by representing a subject but by enacting it in time. For Le Troter, writing operates within the same vibratory field as sound: not as a stabilizing force but as another site where language is disarticulated, made rhythmic, affective, and strange. Rather than reinforce the hierarchy of reason over resonance, her written works contribute to a practice of voicing that is always contingent, embodied, and open to transformation.

While Cavarero grounds her ethics of vocal expression in the distinctiveness and recognizability of each voice, revealing aspects of gender identity, Kristeva and Voegelin present a more fluid and rebellious notion of vocality, one that does not necessarily affirm identity but can instead unmake or suspend it. For them, the voice doesn’t always correspond to identity; it can conceal, distort, fragment, or refuse to signify. Cavarero’s focus on the individual voice as a marker of the self implies a certain level of coherence or recoverability in subjectivity. In contrast, Kristeva’s semiotic theory and Voegelin’s sonic ontology complicate that notion of recoverability.

In Le Troter’s work, this tension plays out in how voices are composed, fragmented, and disarticulated: they are not always heard as affirmations of presence or selfhood, but as evidence of systems that ventriloquise, flatten, or instrumentalise vocal expression. Her polyphonic compositions do not seek to return us to the integrity of a speaker, but to immerse us in a field where the voice exceeds or escapes the subject entirely—where it vibrates, repeats, or glitches in ways that generate new sonic subjectivities. If Cavarero invites us to listen to someone, Le Troter invites us to listen through them, not toward identity, but toward the forces, institutions, and desires that shape the very conditions of vocal emergence. Here, voice as a sonic event that opens up the political: the sonic doesn’t merely reflect the world—it builds worlds.

Listening as World-building

Le Troter, along with other artists of her generation, such as Hannah Lippard, Carly Spooner, Nora Turato, and others, reactivates pre-linguistic spaces of desire, disorientation, and creative possibility. Often felt as intimate or unsettling, moaning, humming, breath patterns, grotesque vocalisations, saliva sounds, and screaming reveal much about us as listeners. For Kristeva, our hesitation or rejection of these sounds is the precondition for the formation of subjectivity. Accordingly, an “I” is built by pushing away the abject—as she notes, “Abjection is what disturbs identity, system, order. What does not respect borders, positions, rules.”8

In sound sculptures such as Racine, Pistil (2024) or Le Corps Living Room (2023), abjection doesn’t respect the pernicious, long-standing divides that have separated nature from culture, and self from the world. Instead, it reveals these divisions as mere abstractions made to present themselves as material realities. Abject sounds comprise rhythms, frequencies, syncopations, and multiple overlapping timeframes that go beyond conventional linear representations of experience and our traditional understanding of listening as an exclusively auditory experience. In an effort to de-essentialize the ear and denaturalise listening, Le Troter creates sonic environments where the voice is intensely experienced—not merely a sign of fixed identity or clear expression, but rather a flexible substance that leaks, loops, and circulates.

Her installations and texts insist on listening as an embodied, disoriented, and often ambivalent encounter—a way of being with sound that resists capture by dominant regimes of meaning or ability. Through repetition, saturation, and disarticulation, she exposes the mechanisms by which voices are shaped, regulated, and standardised, particularly within bureaucratic, corporate, or medical institutions. Yet, in those very same mechanisms, Le Troter finds potential: a kind of acoustic residue, a surplus that slips through semantic closure and gestures toward what exceeds the frame of the audible, the proper, or the useful. What emerges is a politics of vocal abjection—not merely as a rejection of the clean and coherent, but as a sonic practice that collapses the nature/culture and self/world binaries. Her work navigates the semiotic chora, as theorised by Kristeva, where rhythm, tone, and the bodily grain of the voice persist before and beyond structured language. It is here that listening becomes a relational, affective, and situated practice—a mode of being with and within voice, rather than simply receiving it.

Le Troter (...) has developed a practice that listens not simply to what is said, but to the fractures, hesitations, and silences language carries within it.

In addition to her audio works, she has published two books, Claire, Anne, Laurence (2012) and L’Encyclopédie de la matière (2013), which laid the groundwork for her sustained engagement with the sonic and sensorial dimensions of language. In her latest script, La Cithare de Capivacci (2025), Le Troter deepens her exploration of the voice as an embodied and unruly force. Through the mythopoetic figure of Dr. Hieronymus Capivacci, who bites into his zither in a fit of escalating jealousy over the instrument’s restfulness, biting becomes a tactile, sonic ritual — absurd, erotic, and almost sacred. The narrative slips into a speculative dialogue between Dracula and Laurie Anderson, who dream of founding an “Academy of Biting,” a space of choreography, ritual, and spiritualism where biting is celebrated as both resistance and ecstasy. In a final fragment, a Hendrix-like figure gnaws his guitar in a gesture of frustrated desire, linking bodily violence to class rage, grief, and sonic refusal. Where Le Troter’s earlier works exposed the flattening effects of institutional and bureaucratic language, La Cithare de Capivacci turns toward performative violence — biting, chewing, distorting — as a means of reclaiming vocal agency. The imagined “Academy of Biting” echoes her earlier polyphonic ensembles: spaces of sonic alliance grounded in disarticulation.

Le Troter’s relationship to sound began during her studies in sculpture at the School of Art and Design in Saint-Étienne, where access to an audio recorder enabled her to develop a form of acoustic sculpture based on her own voice. One of her first pieces, Fifi, Riri, Loulou (2011), was inspired by the French Fluxus artist and thinker Robert Filliou’s notion of autrisme — a neologism meaning “otherism.” Conceived as an alternative to both altruism and egoism, autrisme imagines a mode of being-with others not through sacrifice or domination, but through mutual creative coexistence9. Filliou’s philosophy of art as a shared, everyday practice — radically open to difference, play, and transformation — resonates deeply with Le Troter’s recorded improvisations, which she cuts and reassembles to create a voice that becomes-other to itself: disrupted, reframed, and opened.

Over time, Le Troter began to work with idiolects, sociolects, and layered repetitions, sculpting speech as one might shape material. Through this convergence of editing, sampling, bodily vocality, and sculptural thinking, she has developed a practice that listens not simply to what is said, but to the fractures, hesitations, and silences language carries within it. Her work insists that the voice is never neutral or disembodied — it is always situated, mediated by affect, structure, and power. Yet rather than decode or resolve these mediations, Le Troter amplifies them, creating sound sculptures and listening environments where voices become porous, unfamiliar, rhythmic, and strange. In doing so, she repositions listening as a critical, intimate, and destabilising act. Whether engaging with the erotics of vegetal metamorphosis, the loops of institutional scripts, or the spectral presence of anonymized donors, her compositions articulate a sonic aesthetics of refusal — a refusal of clarity, of containment, of clean speech. What emerges instead is a practice of coming to voice through relation, where meaning gives way to vibration, and where sound opens onto new possible relations to language, to time, and to one another.

Tina M. Campt, Listening to Images. Durham: Duke University Press, 2017, p.42.

Salomé Voegelin, The Political Possibility of Sound: Fragments of Listening. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018.

The quotes by Anne Le Troter are drawn, for the first, from an Interview by Éva Prouteau for the exhibition Parler de loin ou bien se taire (At Distance Speak, or Hold Your Tongue), Le Grand Café, centre d'art contemporain, 2018 and, for the second, from a sound piece by Anne Le Troter, written subsequently and about this same exhibition, titled Case Sensitive, 2020, Nasher Sculpture Center Collection.

bell hooks, “Choosing The Margin As A Space Of Radical Openness” in Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media, No. 36 (1989), p.23.

See Adriana Cavarero, For More Than One Voice: Toward a Philosophy of Vocal Expression. Translated by Paul A. Kottman, Stanford University Press, 2005.

See Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection. Translated by Leon S. Roudiez, Columbia University Press, 1982. And Julia Kristeva, Revolution in Poetic Language. Translated by Margaret Waller, Columbia University Press, 1984.

See Salomé Voegelin, Sonic Possible Worlds: Hearing the Continuum of Sound. Bloomsbury Academic, 2014. And Salomé Voegelin, The Political Possibility of Sound: Fragments of Listening. Bloomsbury Academic, 2018.

Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection. New York: Columbia University Press, 1982, p.4.

Robert Filliou, Teaching and Learning as Performing Arts. Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1970.