Drawings, anecdotes, creative processes, references, photographic images arranged in piles, films, places, books, art studios, memories, relationships, issues of Turpentine1 and paintings. This list indistinctly enumerates works painted and drawn by Jean-Luc Blanc, found objects of various types, as well as discursive practices and even space-times. Elements that constitute the paratactic ensemble activated by the artistic practice of Jean-Luc Blanc.

The parataxis, as a stylistic device and mode of syntactic construction, differentiates itself from the sheer juxtaposition of its constitutive elements without any explicit subordination or coordination. The fissures created by the juxtaposition of the various elements of the parataxis must be filled, either by the person who is faced with them, by employing their own referential horizon, or by the interactions between the elements themselves.2

All these human and non-human objects communicate with each other as equal actors in a unique network devoid of any ontological distinction, such as defined by Bruno Latour in his theoretical work on the actor-network.3

In this text, I therefore chose to let the objects (in every sense) express themselves without establishing preliminary hierarchies, and to question them according to the roles and modes of interaction they assume in the world of Jean-Luc Blanc. I chose to ask the following question: if instead of limiting himself to the role of the painter, Jean-Luc Blanc is both the actor and orchestrator of his network, how does he liberate the expressiveness of all these objects, how does he grant them their agency, their capacity to act?

From spatial to temporal contextualisation

... the work of Jean-Luc Blanc lends itself to being recomposed into constantly renewed constellations made up of images, paintings, anecdotes, drawings and emotional bonds.

By analysing practices in architecture and contemporary art in his book After Art, theoretician and art historian David Joselit attempts to apprehend the specificity of artistic creation in the digital age, which is characterised by the omnipresence of an almost infinite number of images. To him, contemporary artistic creation distinguishes itself through two operations: the one that has to do with what he calls the epistemology of research, in other words the implementation of operational modes enabling the spotting of images like Google’s algorithm does, and the operation of assembly as formats, the dynamic mechanisms that aggregate content. These formats are not limited to specific mediums, they have more to do with energy fields than distinct objects. In this way, their specificity consists in composing configurations of links or connections.

The sense of the term ‘format’ here is the one it takes within Joselit’s theoretical framework: “Simply put, a format is a heterogeneous and often provisional structure that channels content. Mediums are subsets of formats - the difference lies solely in scale and flexibility. Mediums are limited and limiting because they call forth singular objects and limited visual practices, such as painting or video.”4

In his paintings of images, Jean-Luc Blanc produces appropriationist transpositions from one medium to another. Indeed, the work of Jean-Luc Blanc lends itself to being recomposed into constantly renewed constellations made up of images, paintings, anecdotes, drawings and emotional bonds. The creative process and its stages, the chronotopic blurring and the artist’s a posteriori interventions on his paintings (cf. the Bonnard syndrome5) require the interpretation of Blanc’s artistic practice as a format in the sense employed by Joselit. He sometimes alters finished paintings. “Once, I altered a painting I bought, and it disappeared. Another time, it was an improvement, because the painting was much better after the alterations, but it was no longer the same painting, I had moved on to another format.”6 These phenomena do not prevent the interpretation of the dynamics at play within a single piece, for example a painting, but that interpretation must contribute to understanding the role of the work of art within the wider network of Jean-Luc Blanc’s work.

The dynamic formats Jean-Luc Blanc implements are not only set within a spatial logic, but also a temporal one. The temporality of his works is just as much in the past, through the transposition from one medium to another (from photograph to painting) following the rules of his creative process, as it is in the present through the configuration of the network in which they find themselves at a given time, and even in the future, through their potential reconfiguration into new formats that interact with other works, objects and discourses.

To describe this process, one needs to take a close look at every step, as in Jean-Luc Blanc’s work, these steps prove to be works in themselves.

The city of images

Four constructions halfway between skyscrapers and Mayan pyramids rise towards an artificial sky. They rest upon a mirror ground, and their reflections double them up identically against the placidity of a motionless lake. These buildings are temples dedicated to the storage of an infinite number of images, one image on top of another. They quietly wait for their servant, Zed, to come and feed them by laying other images on top of them, thus enabling them to change their size and appearance. From time to time, the towers give Zed one or several of their images to reward him for his sacrifice. It’s because they consider that their balance needs to be renewed and that the image is ready to depart for new shores. Zed quietly navigates on a boat loaded with images, and as he leaves the city, he casts his gaze upon it one last time.7

Neal Stephenson, in his novel Snow Crash8 (1991), was one of the first writers (inspired by William Gibson’s 1984 novel Neuromancer) to imagine a virtual world: the metaverse in which human beings could interact without moving, plugged in to a device in the analog world. What is the connection with the work of Jean-Luc Blanc, who expresses a certain distrust for information technology and whose work is decidedly analog?

In the digital age, which gives us access to an infinite number of images, Joselit considered the production of contemporary art as relating to an epistemology of research. Its relevance no longer resides in the creation of content, but in the research and configuration of that content, as it grants it a new signification.9

Jean-Luc Blanc welcomes images in his home and makes piles with them, odd landscapes resting on his floor, reminiscent of the piles created by a great many artists, from Marcel Broodthaers to Wade Guyton, or of cities in a science fiction novel or movie such as Metropolis or Los Angeles in Blade Runner. These found images, he receives them from his hairdresser or from a friend. Some become part of his ‘Traumatic Encyclopaedia’, a collection of large binders in which he compiles and assembles them, before sometimes painting them.

By creating his own private intranet made up of a plethora of images, Jean-Luc Blanc employs in his creative process an epistemology of research, insofar as he produces new formats10 to receive new images within them.

Moving images

As in the 2020 painting Fireman, some of the images Jean-Luc Blanc uses for his paintings are movie stills. By using a still, an image removed from the visual and narrative context it belongs to (the circulation on the reel), Blanc transposes it from one role – one image among 24 per second within a film – to other forms of circulation, and from one form of cultural economy – the motion picture industry – to that of art, with its own commercial functioning, from galleries to private and public collections, and its own means of visualisation, from exhibits to catalogues.

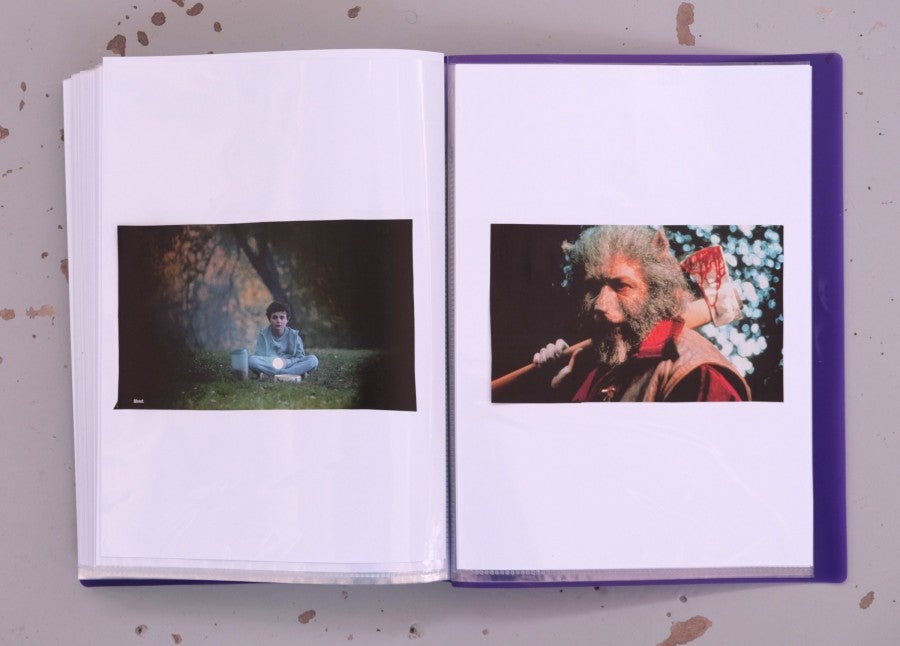

When Jean-Luc Blanc conducts an initial configuration of his found images by creating the volumes of his Traumatic Encyclopedia, he juxtaposes two images on a double page until each volume is constituted: “You see that when you do image calibration, all you’re doing is finding links between colours, but that creates a weird unity where temporality can shift from one image to another. Brion Gysin and William Burroughs spoke of a third mind to designate the relation between two images.”11

This library constitutes, returning to the semantic field of the digital world, a kind of huge server that puts visual knowledge at the disposal of future activations. In the manner of its Enlightenment predecessor, the vocation of the Traumatic Encyclopedia is indeed to gather the sum of its author’s visual knowledge. Consequently, it represents one of the energetic centres of Jean-Luc Blanc’s network of productions, insofar as the artist writes and enters in it new entries and draws from it material that is reactivated in the form of paintings. This dual movement is reflected in the double pages of the Encyclopedia itself, whose name calls forth both the trauma endured by the images during their reconfiguration and the trauma imposed upon the reader-viewer who opens its pages.

The artist’s process is therefore in line with the definition that Joselit gives to what he calls “network painting”: “In network painting, aesthetic labor consists of carrying objects from one historical, topographic, or epistemological position to another (and back again). Instead of forming a neo-avant-garde, as art of this period is often condescendingly labelled, network painting continues modern art's task of redefining the relation between subjects and objects through new modalities of aesthetic work. Here such labor consists of the circulation of images through successive thresholds of attention and distraction – arguably the most important new source of value in the postwar period, whose economic engines range from television to the Internet.”12

It is inside Jean-Luc Blanc’s studio that we can witness the deployment of such a network. As the artist’s place of living and activity, the studio enables us to grasp his work through the chronotopic coherence of all its manifestations, from the creative process and its material traces to the activation of paintings through Jean-Luc Blanc’s words.

From a fantasised Orient to the living portrait: cultural and artistic appropriations

“There is something that has to do with the gaze: it is not enough that the painting is structured around a figure, that figure must organise itself around his gaze – around his vision or his clairvoyance. What does he see, what must he see or look at? That is of course the heart of the question.” Jean-Luc Nancy13

... they are stripped from their initial use, be it for advertising or something else, and from the stereotypes they carry, and become ready to play a different role.

Hanging from the side walls of Jean-Luc Blanc’s Parisian studio, two boys donning a keffiyeh face each other. Sitting with the artist at his studio table, drinking kombucha, sweat stains on my blue shirt because of the heatwave, our gaze rises from a volume of the Traumatic Encyclopedia we are perusing to the two painted portraits that are looking at us. Jean-Luc Blanc tells me they were made despite other more urgent pressures, in a way they imposed themselves and slipped into his creative process.

Is it a coincidence that these two paintings are the only ones exhibited in Jean-Luc Blanc’s studio when I visit? The fact they are hanging across from each other echoes the artist’s presence and mine, as we get in between their crossing gazes. Additionally, their simultaneous presence, as well as the duplication they represent, are reflected in their creative process.

In effect, the two portraits carry within them the traces of various acts of successive adaptations and appropriations. Originally, they are probably advertising images from the late 70s showing a blond boy from a fantasised Orient suffused with imaginary nobility, like the distant descendent of a Pierre Loti novel. Their visual language reused for commercial purposes is borrowed from that of David Lean’s film Lawrence of Arabia, which was itself a cinematographic adaptation of the novel Seven Pillars of Wisdom by T.E. Lawrence.

The stages of the two subjects’ journey between successive adaptations and appropriations, from the literary genre to the cinematographic and then to the visual regime of advertisement, culminate in their pictorial appropriation by Jean-Luc Blanc, their renewed life in the form of paintings.

The photographic images Jean-Luc Blanc uses to create his paintings belong to the realm of indexicality. Indexicality, in the semiotic theory of Charles S. Pierce14, indicates the immediate and physical link between the sign and what it represents. Photography, itself a pictorial sign, carries the immediate trace of the represented objects or subjects through their imprinting on the light-sensitive layer of the film.

What happens when Jean-Luc Blanc takes hold of these photographs to transpose them into painting, which is itself a pre-indexical medium?

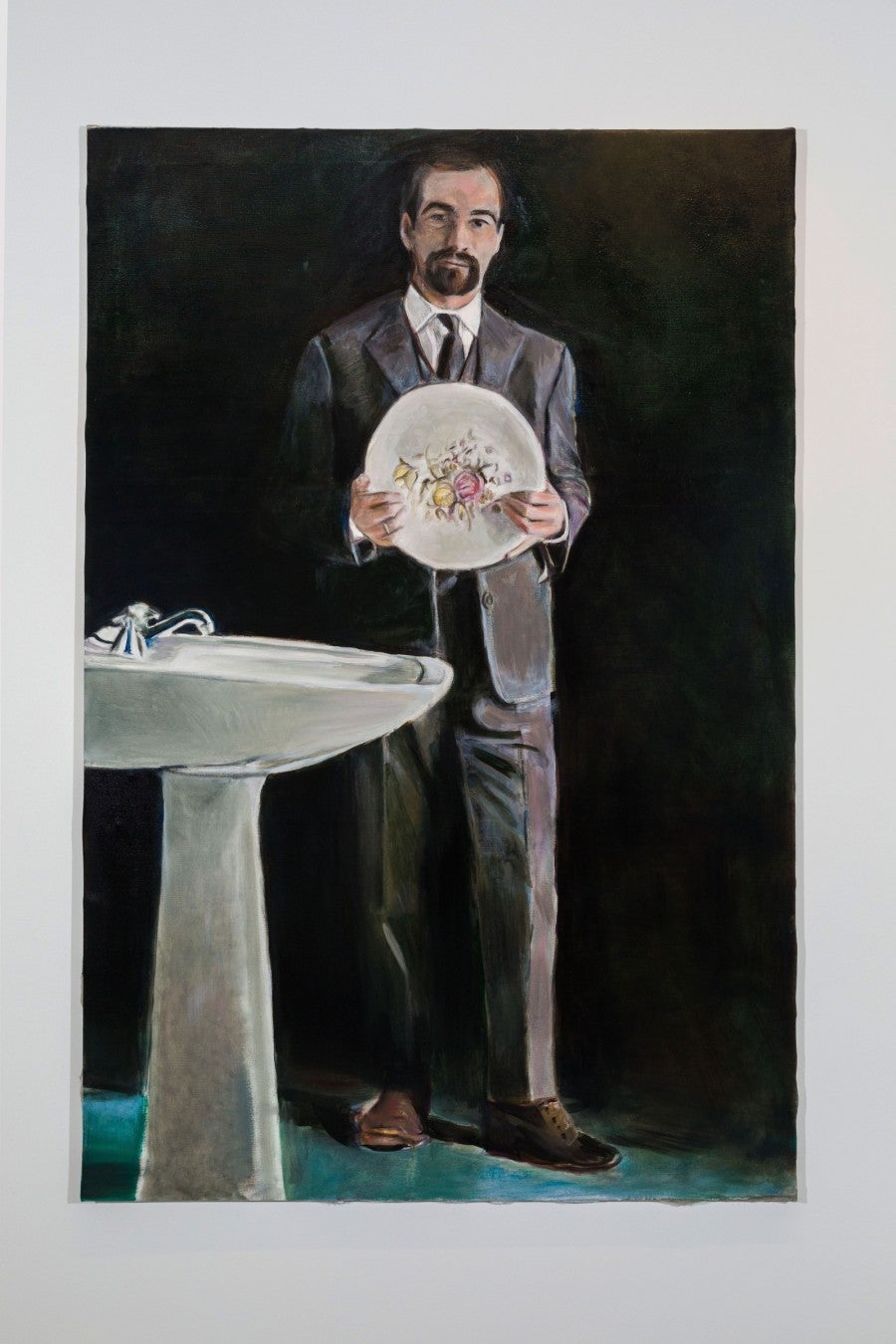

On one hand, it isn’t without irony that these found images, infinitely reproducible artefacts of popular and/or commercial culture, are elevated to the status of a painting, which remains the most sought-after commodity in the art market, due to its uniqueness and its attribution to the artist. However, what is even more characteristic is that by resorting to painting, a medium traditionally associated with an artist’s intentions, Jean-Luc Blanc alters the mode of presence of the initially photographed subjects through their transposition to a different regime of attention. The painting carries with it the attention that was given to it by the artist, the brush strokes are traces of his work and by extension traces of the artist himself, demanding the attention of the viewer.

According to the art critic and essayist Jonathan Crary, since modern times, it is through painting that artists have countered new constraints imposed on attention: distractions caused by new technical devices and the access to a multitude of visual information on one hand, and industrial world disciplinary requirements regarding work and education on the other.15

Lastly, from the moment the painting enters the world and begins to circulate in it, it already carries with it not only the artist’s emotional charge and the traces he left, the artist also provides it with a score, etching into the painting the conditions of its possible futures. In the case of Jean-Luc Blanc’s paintings, this potential is reinforced by the cropping he undertakes: by centering the composition mainly on the subjects’ bust and face, he ushers them into the genre of the portrait. For Jean-Luc Nancy: “The identity of the portrait is entirely in the portrait itself. The figure’s formal ‘autonomy’ engages nothing less than the autonomy of the subject that surrenders in it and like it, like the interiority of the painting devoid of depth, and consequently also the autonomy of the painting that creates the soul here itself. The person ‘in itself’ is ‘in’ the painting.”

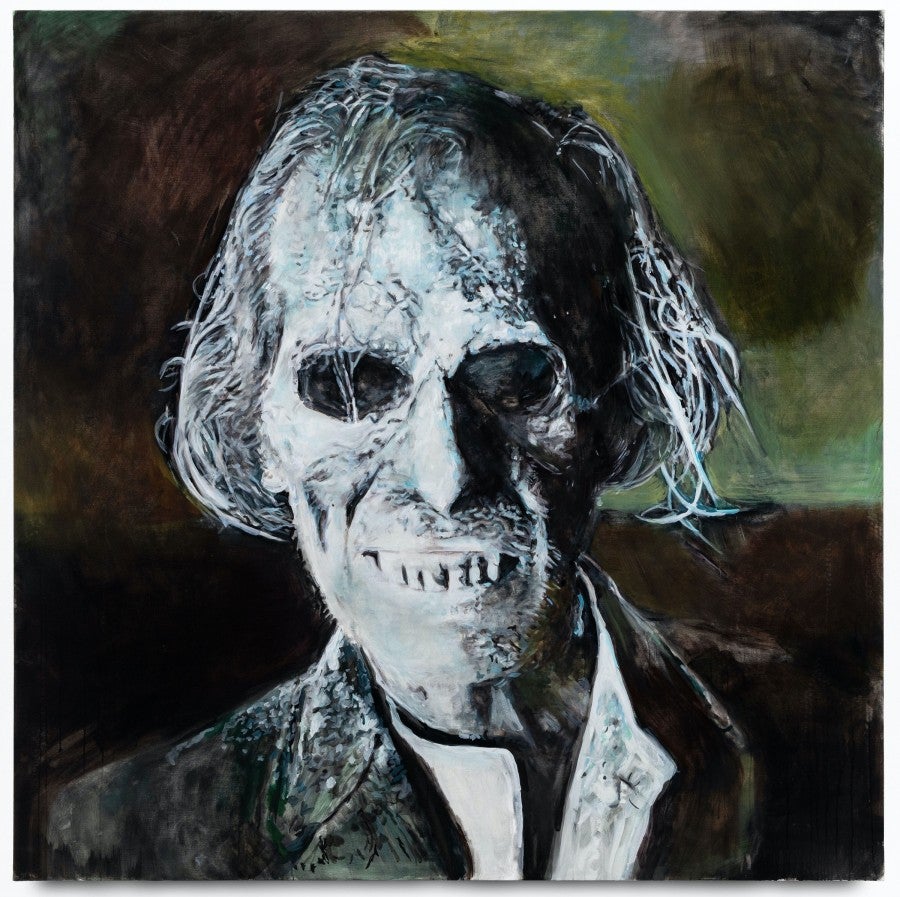

From this definition, there is only one small step towards the attribution of an almost animistic agency to the painting, and specifically the portrait. In his influential book Art and Agency, English anthropologist Alfred Gell looks at the capacity of works of art to substitute persons within a network of relations between agents and patients, and therefore to possess a certain agency. It is no coincidence that the active and animated portrait – the character that starts moving and sometimes even steps out of its frame – became a major topos in the genre of horror, from the first gothic novel The Castle of Otranto by Horace Walpole (1764) to the photograph coming to life in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980).

The portraits painted by Jean-Luc Blanc, while they retain traces of the photographed person’s indexicality and of the cultural references to the era in which they were made, offer a stage to actors and actresses capable of acting between paintings, between objects and thus of taking an active place in dynamic networks that can be reconfigured. In this way, they are stripped from their initial use, be it for advertising or something else, and from the stereotypes they carry, and become ready to play a different role.

Two Paintings (Addition & Subtraction)

1 - Addition

“What is the subject of the portrait? None other than the subject itself, absolutely. Where does the subject find its truth and effectiveness? Nowhere else than in the portrait. Therefore, there is no subject elsewhere than in painting, just like there is no painting other than of the subject. In painting, the subject goes under (it ‘comes back to itself’); in the subject, the painting surfaces (it exceeds the façade). In that moment emerges in one draught, not subject nor object, art, or the world.”16

She is wearing, painted on her face, a sort of yellow butterfly on a blue background, maybe for a costume ball or to shoot a movie scene. Is she embodying a moth for a wild party? Her gaze eludes us: did she just look at us, or will she in a few seconds? The artistic makeup immediately applies on the person’s skin the identity she wants to adopt by attributing her a Jungian persona17 before she even deploys it for a movie scene or any other social circumstance like a costume ball. Her potential agency, the role she will play on the scene of social interactions, is hence etched onto her skin. By transposing her to the medium of painting, Jean-Luc Blanc creates a parallel between the addition of a layer of makeup and the process of painting, which also operates through the addition of successive layers.

Blanc chooses to showcase these portraits that stare at us highlighting their absence/presence, he gives them a platform through the frame. Their staging and its respective theatricality are part of an approach similar to that of artists such as Lucie McKenzie, Paulina Olowska and Birgit Megerle. In their work, these artists look at the modalities of the staging of their paintings’ subjects from a feminist perspective, by resorting to references from the worlds of art, history, theater, as well as interior decoration and fashion design.

In this way, Jean-Luc Blanc doesn’t just transpose a found photographic image emanating from popular culture to the medium of painting, he underlines the very gesture of painting by playfully translating the showcasing that is specific to makeup into the arrangement of pictorial values specific to modern painting.18

2 - Subtraction

She seems taken straight out of an ad. Her face is calm, her gaze aimed directly at us, her hand lightly resting on her left cheek forms the symbol of a gesture. Her fingers are covered in a layer of cream she is about to apply onto her face. She thus becomes a commercial allegory of beauty, carrying the promise that emulating her gesture will grant her beauty and the texture of her skin. To the logic of accumulation, of accessing beauty through repeated layers of cosmetic products, the painting The Perfect Cream opposes subtraction, a visual equivalent to the approach of writer Mary Robison, who uses this term to define her literary process opposed to minimalism.19

The layers of cream on the protagonist’s fingers become layers of white, a step towards the erasing of the pictorial subject. The image still changes the narration, it veers away from the logic of the source image and adopts the logic of painting. The grey white of the painting’s background can also be seen in the gleam of her hair and the white highlights on her forehead and cheeks. The portrait is thus kept in limbo between two possible states: is it an unfinished painting or a painting that is being deconstructed by the gesture of its subject, who becomes the painter of its own subtraction?

The studio as a network for circulation

In the middle of Jean-Luc Blanc’s studio, not far from the table we are sitting at, a composite sculpture made of wire and fabric is hanging in space like an organic mobile, stretching its twisted and multicoloured ramifications with a convulsive momentum. The artist uses it as a hanging rail, its aspect changing according to his sartorial whims and laundry cycles.

And in the background, protecting Jean-Luc Blanc’s nocturnal activities from the artificial light coming in from the street, disparate swathes of cloth of varying quality and heterogeneous origins form a curtain hanging in front of the window that runs along his studio. The aspect of this curtain also changes with the fabric offerings the artist receives from friends, creating a commemorative procession of both living and lost friendships.

Surrounded by these objects, constantly observed by the dual gaze of the two oriental figures, I can’t help but think of Marc-Camille Chaimowitz being threatened with eviction from his London artist residency in the 1960s, following his denunciation by fellow artists who occupied other spaces in the same building. While they were hard at work producing large scale paintings under the influence of the last breaths of abstract expressionism, they accused him of not making serious art and instead occupying his days inviting friends for tea, surrounded by pieces of furniture he had created.

My experience visiting Jean-Luc Blanc’s studio bears many similarities with that of the visitors of Opera Rock, his monographic exhibition held at the CAPC in Bordeaux in 2009. There too, Jean-Luc Blanc’s pieces constituted a network alongside works by 45 other artists, as well as “various objects, antiques, jewels, crystals, curiosities and naturalia (boxes containing flies, snakes, mummified hands, sponge skeletons, etc.)”20 In the semi darkness, the artworks and objects were presented in an elaborate spatial dramaturgy and formed an associative parataxis whose cohesion was ensured by a soundtrack especially created for the exhibition.

Resorting to the genre of live performance in the form of a rock opera that gave the artworks the role of protagonists underlines the importance of narrative forms within Jean-Luc Blanc’s artistic practice. His interest in the power of words to invoke images (and vice versa) is also illustrated by his habit of listening to a movie several times before he watches it. Instead of muting the sound, he cuts the image.

The imagined and illustrated objects of speech

Before I got interested in Jean-Luc Blanc’s work, I got to know the person. Sitting on the steps of a house by the Seine not far from Fontainebleau, we talked through most of the night. Jean-Luc Blanc is cultivated and charming, he has that type of refined humour that makes him a fascinating narrator. He could very well be featured in a contemporary version of the book Born under Saturn by Margot and Rudolf Wittkover, in which the authors examine the eccentric lives of Renaissance artists.

When Jean-Luc Blanc was a child in his birth village, his family lived in a house adjoining a disused slaughterhouse. To get to his room, Blanc had to cross a huge cold room in the middle of which sat an enormous monolithic stone table surrounded by a moat that allowed the blood to be evacuated.

He also tells me that the balcony of his apartment in Nice is filled with cacti. These succulents grow so fast that not only do they no longer let him access his balcony, they also cover the entire façade across to his neighbours’ balconies.21

Back in Geneva, when I think about Jean-Luc Blanc, I think about the passages that open up with the space-times featured in the anecdotes the artist likes to evoke.

The anecdote, as a so-called minor literary genre insofar as it stands in opposition to great historic tales, is well suited for particular agency when combined with other anecdotes, thus creating parts of an imaginary spatiotemporal architecture comprising disparate elements that range, in Jean-Luc Blanc’s personal mythology, from the slaughterhouse to his balcony in Nice. The anecdote therefore has the potential to give multiple accesses to reality, far from the broad strokes of history, as is for example shown in the writings of the German philosopher, director and writer Alexander Kluge, which gather a multitude of short stories and anecdotes, thus crystallising their “magic links” in the manner of a meta-chronotope.

Their fragmented nature, evocative of Walter Benjamin’s micrological method, allows the anecdotes to form constellations, to be integrated into Jean-Luc Blanc’s formats such as genre painting, as a pictorial transposition of the genre of the anecdote owing to its sturdy anchoring in space, taking place in movie sets. By giving his pieces a film set that enables them to narrate themselves and improvise their roles, Jean-Luc Blanc’s creative practice, his attitude, his gestures, his creative process foster the agency of his works of art.

Turpentine is a zine co-published by Jean-Luc Blanc, Mimosa Echard and Jonathan Martin. www.turpentinemagazine.net

The use of the parataxis as an interpretative framework for Jean-Luc Blanc’s work was inspired by the essay by artist and writer Angus Cook about the artist Kai Althoff in Souffleuse der Isolation, Zürich, JRP Ringier, 2013.

Madeleine Akrich, Michel Callon and Bruno Latour (ed.), Sociologie de la traduction : textes fondateurs, Paris, Presses de l'Ecole des Mines, 2006.

David Joselit, After Art, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2013, p. 52.

Judicaël Lavrador, « Le Syndrome de Bonnard : l’art de ne jamais achever une œuvre », in Beaux Arts Magazine, n. 388, October 2016, pp. 104-109.

Quotes by Jean-Luc Blanc collected during our encounters.

Taken from a non-existent science fiction film written by the author. The character of Zed refers to the protagonist of the film (and novel) Zardoz (John Boorman, 1974), one of Jean-Luc Blanc’s favourite movies. The artist incidentally re-used an image of Zardoz in a mural painting exhibited at the Busan Biennale in 2018.

Snow Crash, Neal Stephenson, Bantam Books, 1992.

David Joselit, After Art, 2013, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2013, p.58.

Ibid.

CRASH Magazine issue 90, 2019. Interview of Jean-Luc Blanc by Lise Guéhenneux.

David Joselit “Reassembling Painting”, in: Manuela Ammer, Achim Hochdörfer, and David Joselit, Painting 2.0 – Expression in the information Age, Munich, Prestel Verlag, 2016, p.173.

Jean-Luc Nancy, Le regard du portrait, Paris, Éditions Galilée, 2000, p. 18.

Charles Sanders Pierce, What is a Sign?, 1894 https://www.marxists.org/reference/subject/philosophy/works/us/peirce1.htm

Jonathan Crary, Suspensions of Perception - Attention, Spectacle and Modern Culture, Cambridge, MIT Press, 2001, pp. 281-358.

Jean-Luc Nancy, Le regard du portrait, Paris, Éditions Galilée, 2000, p. 1.

https://www.universalis.fr/encyclopedie/persona/

Yves-Alain Bois, Painting as a Model, Cambridge, MIT Press, 1993.

Interview of Mary Robison by Maureen Murray in BOMB Magazine, 2001. https://bombmagazine.org/articles/mary-robison/ :

MM: But initially, how did you feel about being categorised as a Minimalist?

MR: I detested it. Subtractionist, I preferred. That at least implied a little effort. Minimalists sounded like we had tiny vocabularies and few ways to use the few words we knew. I thought the term was demeaning; reductive, clouded, misleading, lazily borrowed from painting and that it should have been put back where it belonged.

Alexis Vaillant, OPERA ROCK - Jean-Luc Blanc, Berlin, Sternberg Press, 2009.

As told by Jean-Luc Blanc during our encounters.