What washes ashore…

Piles, sacks, stacks; rooms and a hallway where make-shift tables and benches teeter under the weight and wash of things; old fabrics, wires, plastic forms, some melted or broken, if plastic can “break”; but also trails of organic material such as rice, or previously organic like a snake’s skin; scavenged off streets in various cities or purchased, in legal venues or dubiously so; and, amongst this miscellany of material, a hanging sculpture, whose separation from what is composing it is not entirely defined. Will the scraps surrounding this sculpture eventually become a part of it? Or were they a part of it but have now been removed? Or are they simply parts of a pile of material that has drifted off its shore, founding a new place to rest under the shadow of this half-finished piece?

I encountered these materials when I met Julien Creuzet at his home and studio, an artist community in Fontenay-sous-Bois. It was a beautiful May Day; hot outside as we sat and drank tea on benches in the sun, cool inside. Paris and other cities in France were braced for labor protests. We were both slightly tired, neither having gotten much sleep the night before. I was eager, however, to see his workspace, having been absorbed by his multidisciplinary show at the Palais de Tokyo a few days before1. Where had the elements that composed the sculptures, paintings, video, word and sound pieces come from? Not merely where did Creuzet find the pieces of textile, plastic, metal piping, wiring, LED lighting and other detritus that compose the interchange of his brilliantly balanced montaged pieces, but why? What inspired the conceptual element of his exhibition? How did he imagine the links between the different pieces in the show—the play of their physical and sonic elements—and our current posthuman climate compromised planet? How did the show change depending on who was navigating it? Simply put: where are we when we are standing amongst his visionary and revisionary fictions? How is he providing a field of sight onto the past and future becomings through his sculptures? Who is we when we are standing there?

I began asking these questions as we made our way out of the sunshine and into the two rough rooms that compose his cramped workspace. Everywhere was something abutting something else, pressing against your elbow, or working its way into my butt whenever I sat or the soles of my sneakers when I stood.

“Excuse the mess,” Creuzet said.

I immediately found myself at the edge of a dizzying array of potential futures.

But it was not a mess we sat within, nor was it a miasma. There was nothing oppressive or unpleasant in the atmosphere that so many associate with disordered space. Instead the studio was resonant with the possible. This is the first thing I wrote down in my notes: how, rather than uncomfortable in the mess, I immediately found myself at the edge of a dizzying array of potential futures. Perhaps I scribbled down my initial feelings sitting amongst the piles because of Aimé Césaire’s profound re-reading of The Tempest2. Who defines the source of pollution in the atmosphere and the nature of the creatures emerging from it? Will it be the prosperous of the earth or those who are the recipients of all the waste that washes ashore?

“Where did you find all this wonderful stuff?” I asked, entranced by Creuzet’s eclectic assortment of material. “I myself pick up shit off the street for small icons I make,” I offered. “But my collection is embarrassed by this richness!”

Some things, Creuzet told me, come from street bazaars, other things he too picks up from the street. Still other things come from his travels. All caught his eye, but not for any specific idea or project he had at the time.

“Of course, some of this I may never use,” he mused.

If I felt at home in his studio this did not mean that my experience was reassuring or redemptive. The world within his studio was neither pleasant nor unpleasant; normative affects didn’t seem relevant. It was as if I were among an enormous pile of facts about the contemporary world. It was as if I was viewing the world from within its wreckage and waste and while the wreckage and waste was reorganizing itself into a new kind of being.

“Yeah, these are fictional stories, I think,” he said, as we looked at some works in progress hanging from the ceiling and partially disintegrating on the concrete floor.

“But also, I am interested in the effects of environmental changes on a whole series of things. Rice, which is a very water-thirsty food crop, is disappearing because water is disappearing and this causes not merely a readjustment of all humans, but specific humans. If the scarcity of rice pushes the price from 2€ to 6 € this is catastrophic for all those who rely on it for their basic food needs. Water, rice, genetic capitalism, the plastic sacks that foods are delivered in—I use all of these elements to signal the opacity and differences of humans, non-humans, posthumans.”

Julien Creuzet’s work radicalizes Lacan.

The more I sat and listened the more I appreciated how Creuzet has absorbed and re-routed contemporary theoretical discussions about the entanglement of being. Long ago, Jacques Lacan coined the term “extimacy” (extimité) by combining ex– from extérieur and Freudian intimé. He did so to signal the strange topological relationship between the psychic inside and outside. At the core of human subjectivity was an uncanny loop—the Other is “something entfremdet, something strange to me, although it is at the heart of me.”3 We stare at the outside in order to understand our innermost being. “I am that,” says the woman looking at herself in the mirror.

Creuzet’s work radicalizes Lacan. On the one hand, insofar as his art suggests that the internal material substance of all beings—not just psychic life—is always radically extimate. The conditions of our most interior physical and psychic integrity are outside ourselves. Among the materials stacked, slipping, and falling off piles in his studio, and among the works in the process of being sewn together and pulled apart there, was this strange way of pointing to a self. On the other, his works insist we navigate through and listen to a world of posthuman beings. His studio is a hatchery where these new posthumans are composing themselves by pulling into themselves all of the detritus and waste of our contemporary world.

In their parts and whole, Creuzet’s works become less creations of his hand and more hybrid creatures he has found emerging from what has washed up on his shore. This shore—this territory—is bounded and unbounded by the usual nomenclature of space—nations and states, land and water, colonized and colonizers. Bounded and unbounded: it is the simultaneity of open and closed, that interests him.

“I am interested in geolocalization.” Creuzet said using this term to describe both his artistic process and political intent.

Geolocalization…

“What do you mean by geolocalization?

- – Like in the case of rice and water, how local the effects of global events of climate change can be.

- – And how uneven.

– Yes, of course. It is about the precarity of some and then all.”

Sitting at the edge of some composing and decomposing sculptures in his suburban studio, we talked about the uneven territorialization of global climate change and capital toxicity.

“I am looking to create a different form of temporality and space that would create a new way of thinking about geolocalization. Maybe a different language.”

I promised Creuzet that I would not obsess on an obvious intellectual reference of his work: Édouard Glissant’s relational poetics and his concept of Tout-Monde/All-Earth. Creuzet’s work can hardly be contained within this single territory of thought. His work speaks to an international conversation about the posthuman condition in the Anthropocene; the question of becoming rather than being; and new forms of precarity in neoliberalism. But to understand the social implications of Creuzet’s approach to geolocalization and the new aesthetic language he’s developing around this concept, it seems important to begin by putting his relational objects in connection with Caribbean theory.

If I were tasked with writing an academic essay, I would delve into the rich lineage of thinkers from Martinique and the Caribbean more generally, including Aimé Césaire, C.L.R James, Frantz Fanon, and Sylvia Wynter. Still, Glissant’s concept of the three relations that all things in the world have to each other: tout-monde (the world in its entirety), écho-monde (the world of things resonating with one another), and chaos-mode (that part of the world that cannot be ordered) seems particularly relevant to Creuzet’s work4. For Glissant tout-monde refers to a specific form of being-all-togetherness that is always inflected by the écho-mode and chaos-monde. While the whole world encompasses us all, it does so through a “you and me” or “us and y’all” (an American southern second person plural) rather than the global “we.” The stakes of this different form of consisting the oneness of the one world is painfully clear in how many scholars, scientists and politicians discourse the coming catastrophe of climate change—we are facing an epochal moment; that, if we are not at the end, we are inching quite close. It is undeniably the case that climate change and capitalism’s toxic waste is a global issue; it is our issue. But where it has already hit and how severely—what has washed ashore already—is not; it is an issue between you and I.

It is the fundamentally relational aspect of global power and politics that motivated Glissant’s engagement with his friends Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari. All three began “in the middle” where the figures of the rhizome and the nomad live5. But Glissant places this philosophical premise in the political territory and history of colonialism. The nomad, Glissant argues, has a multiplicity of modes, the two major being circular nomadism and arrow nomadism. Glissant’s somewhat romantic understanding of Indigenous communities underpinned his concept of circular nomadism. “Each time a portion of the territory is exhausted, the group moves around. Its function is to ensure the survival of the group by means of this circularity. This is the nomadism practiced by populations that move from one part of the forest to another, by the Arawak communities who navigated from island to island in the Caribbean, by hired laborers in their pilgrimage from farm to farm, by circus people in their peregrinations from village to village, all of whom are driven by some specific need to move, in which daring or aggression play no part. Circular nomadism is a not-intolerant form of an impossible settlement.”6 Against this rhizomatic mode is the arrow-nomadism (or invading-nomadism) of European colonialism. “[T]he Huns, for example, or the Conquistadors” perfected an “invading nomadism” whose goal was to “conquer lands by exterminating their occupants.”7 As if they were the advanced runners of a spreading plague from which they believe themselves to be immune, “conquerors are the moving, transient root of their people.”8 These followers would root down into the charred landscape, claiming it as property, fencing and commodifying it in a new form of conquest—the conquest of private cultivation.

Glissant was not merely speaking to Deleuze and Guattari but creating a relation between them and his teacher, Aimé Césaire, who in Discourse on Colonialism argued that while “it is a good thing to place different civilizations in contact with each other”, colonization was never about establishing contact only dominating people, land and things9. In other words, Glissant was putting the philosophical and political thought of Césaire, Deleuze and Guattari in relationship in order to create a new language of space, politics, and history.

I was scribbling these notes as I listened to Creuzet talk about how his family came to France; the political-economy of the French Caribbean; the uneven distribution of industrial poisons; differences between claiming a black identity in the US and in France. Space, politics, and history: me and you together and I/us here and you over there. Through our morning we talked about how, yes, we are all increasingly captured by the precarity of neoliberal capital, by the enormity of climate change, by the rise of artificial intelligence. But we are not all captured in the same way, to the same degree, or toward the same future. We are localized by geography, history, capitalism, race, gender, and colonialism to name just a few social technologies.

“When I was in residency at the Rebuild Foundation in Chicago, I would say I was from Martinique. Being from Martinique, I experience a very different meaning of blackness. It is a part of France but European France is over 6500 thousand kilometers away. And in France, unlike in the US, it is sometimes quite hard to speak of being black because of the idea of equality, fraternity and liberty. It is a cliché but true. I am French because Martinique is a French Department and/but I am Martinican nevertheless. My emotions are from Martinique. I grew up there. But we are also French, so my parents, uncles and so many relatives came to work in France through the racialization of economies and the economies of race.”

France found itself in a deep political conflict about the substance of French citizenship and territoriality.

Employing French Caribbean workers, especially in the health services, fit numerous political and economic rationales. While the 1960s saw relatively uncontrolled immigration, stricter policies were put in place in the mid to late 1970s. We do well to remember that this was the exact period that saw the rise of what we now call neoliberalism—a form of flexible, precarious employment that Michel Foucault also described as anarchy-capitalism and biopolitics in his College de France lectures (1972-73) beginning with Society Must Be Defended to The Birth of Biopolitics. Caribbeans served the politics of political nationalism insofar as people like Creuzet’s parents and relatives were technically not migrants even as they could be slotted into flexible, i.e., precarious, employment conditions and lower wage service labor.

Creuzet’s family arrival, as Stéphanie Condon and Philip Ogden note, was part of a much longer period of a Caribbean migration political and economic inflected by the success of the Algerian independence struggle10. France found itself in a deep political conflict about the substance of French citizenship and territoriality. Where was France? What made a French man?

Born in France in 1986, Creuzet grew up in Martinique. While his parents were considering immigrating to France for work in the health care sector, Condon and Ogden report that over 122,000 people born in Guadeloupe and Martinique were living in France in 1982, most of them younger to middle-aged immigrants.

As I sat with Creuzet, surrounded by mounds of trash as treasure, I couldn’t help picturing a set of images in “A Giant Mass of Plastic Waste Taking Over the Caribbean,” which was the headline of a BBC report I read online in 2018. Journalists are canny creatures; they sift among the flotsam for captivating juxtapositions. In this case, an American and European fantasy of the “Caribbean getaway” advertised everywhere and a sea of nasty coagulations, condoms, string, cast-off clothing, plastic water bottles, coke bottles, you name it. Where we might wonder is obvious moral disgust on the historic direction of the tides.

Creuzet’s work neither neglects this moral outrage, nor is it defined by it. As he talked, he embraced the history of his aesthetics and affects (“My emotions are from Martinique. I grew up there”). But he also insisted that this history can only be understood through a probing of the uncanny intersections of pasts and futures that huddle through a place.

Creuzet generously played me some audio tracks from his show at the Palais de Tokyo as well as new pieces he was working on. “I am recording a new song for chlordécone.”

I knew what he was referring to because my colleague at Columbia University, Vanessa Agard-Jones, has been studying the effects of hormone-altering pesticides like chlordecone (or, kepone) on gender and sexuality in Martinique11. The US corporation, Allied Signal Company, began producing chlordecone in its Virginia Hopewell factory in the 1950s. The chemical was banned in the US and France, after an environmental spill in 1970, but stockpiled by planter groups in Martinique and Guadeloupe. Chlordecone was banned in mainland France in 1990, but influenced by these powerful local white, békés, a special provision was written into the law that allowed it to be used in the Antilles until 1993. The interval produced increased levels of bodily maladies (prostate cancer, for example) as well as so-called abnormalities (intersex births, for example). And these bodies—born outside the body-with-organs and confronting an anxious bionormativity—are in turn producing a politics at the material intersection of carnal vulnerability and its chemical legacy.

I told Creuzet about Vanessa’s work because, like her scholarship, his sculptures and installations make me think about both the spatial distribution of precarious wastelands and the resilient creatures emerging within them; about both the fact that these creatures have already emerged from the unjust conditions of Tout-Monde and that they may well be the successor species of this injustice.

What language is needed for this strange new world, that is not new or strange for many people already living along its shores?

A new language of things…

Creuzet’s work abounds in the poetics of language and language of poetry. To fully fathom the geolocalization of his aquart/terrart—how they conjure specific knots among the global networks and geographies of human and nonhuman animals and things—one must delve into the new sounds and languages of things he is hatching.

I listened to some of these sound works in his studio after we’d talked for a while, toured the piles, felt and touched the space. The songs montage different languages (English, French and Czech), different genders, and, if he does make his song of chlordécone, different beings.

“How do you decide what language to record in?

– The language depends on where I find myself. For example, when I went to the Gwangju Biennial, I wrote poetry in Korean.”

Creuzet’s sculptures remained posthumanist entanglements of materials that many humanist viewers might find jarring.

But like the emotional anchor of his work, the sonic and poetic character of Creuzet’s work are knotted together through the local conditions he knows most intimately—while, at the same time always referring to complex and sometimes paradoxical global histories that created these conditions. I am that. That is me. What languages are needed if we are to inhabit the internal relations each of us has to others within our current posthuman, neoliberal, neocolonial condition?

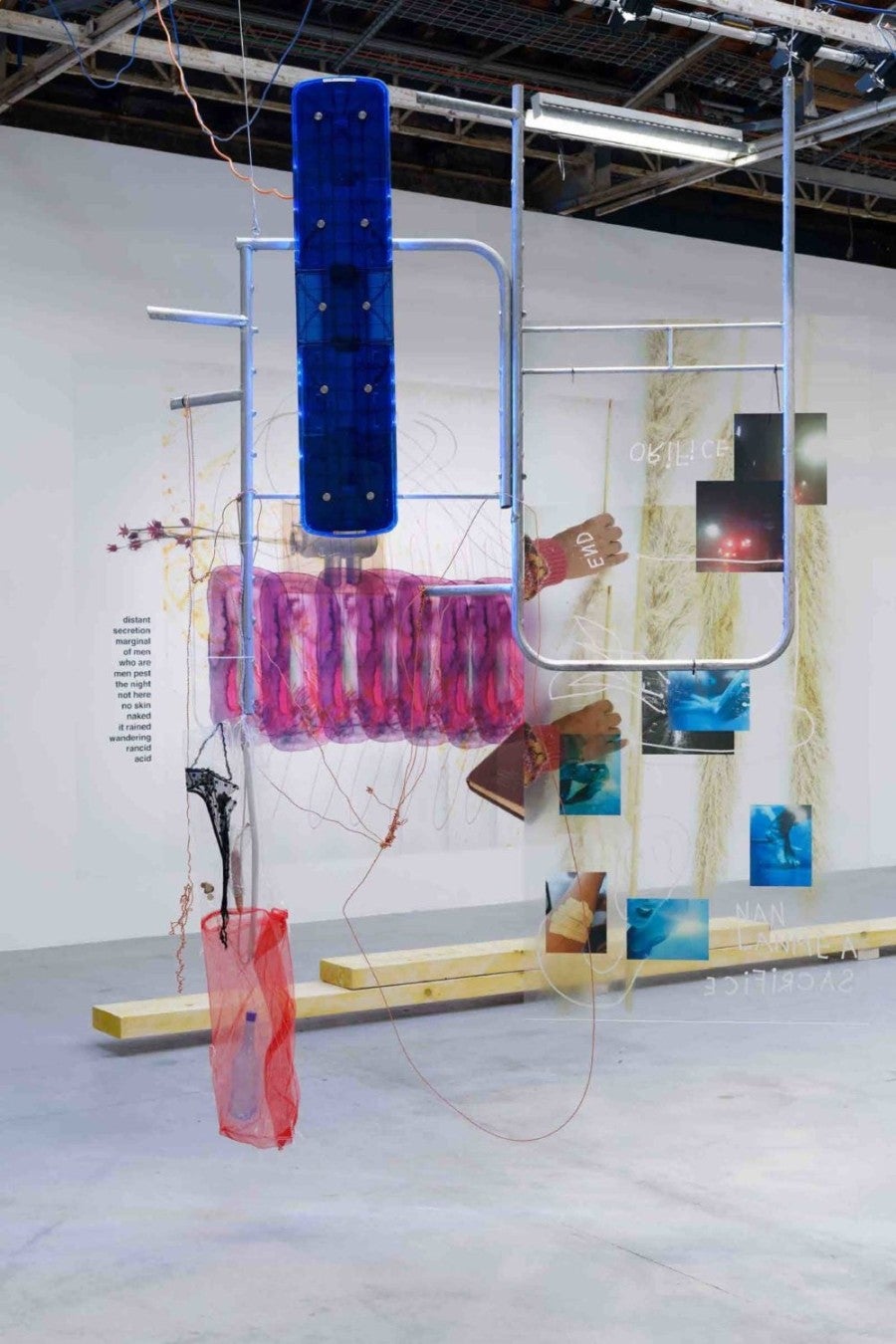

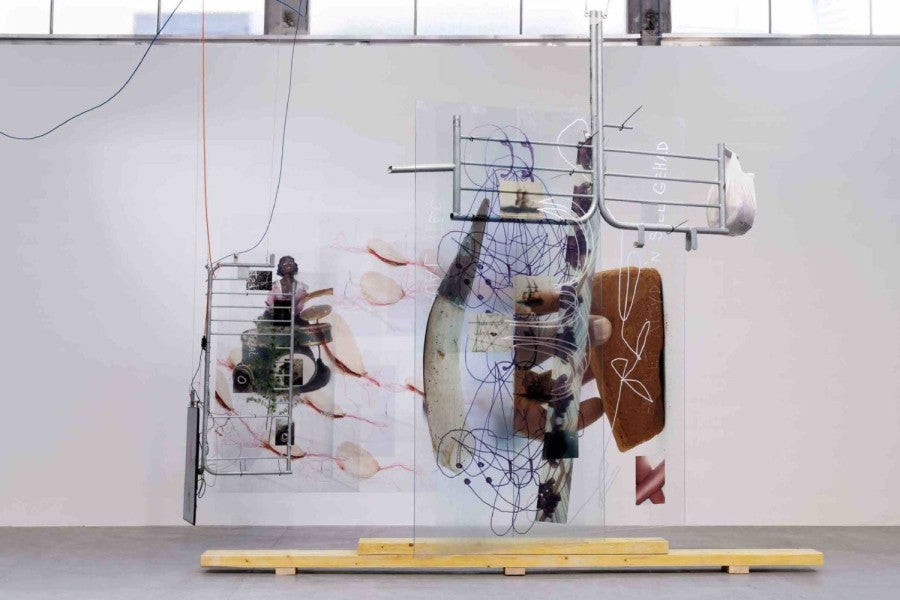

I glimpsed some answers to this question at Creuzet’s show at Palais de Tokyo. His show was far neater than his studio, everything tucked in place. In the main gallery, Creuzet’s sculptures remained posthumanist entanglements of materials that many humanist viewers might find jarring. The posthuman in his work is postorganic, polytechnical, and aesthetically hybrid–no hierarchy of difference is signalled in his use of organic and inorganic material; various technologies of art (video, painting, sewing, etching, plumbing) have equal footing; and waste material is woven into everything. But each sculpture stood within its own skin. One could distinguish one sculpture from another even as each sculpture was a multiplex of flat planes, vertical and horizontal objects, slightly rotating or fixed, often with a flat encased video with images of a dancer. I watched visitors move from one piece to another, as I myself did. The floors of the gallery were swept. The soundscape rich, captivating, perfectly rendered as a supplement in the old deconstructive sense. In a smaller black box, one of Creuzet’s videos played, entitled Head-to-head, hidden head, Light (2017).

The spatial discipline of the institution did not, however, diminish the experience I had in Creuzet’s crowded studio; it simply registered a different moment of the emerging beings Creuzet produces; it simply changed where perhaps, and how, a viewer found the flickering between the opacity and clarity of contemporary existence. Having pulled their entrails within their corporeal sacks, the works showed and refused their compositionally errant ancestry—the outlandish harmony of each piece. Here, a collage of organic and plastic fabrics and castoff clothes stitched roughly together on a bright yellow workbench; there paper, fabric, video, and whatever else might (not) suit, encased in thin plastic sheathing and held together with ordinary aluminum piping; and over there LED lights, drawings, and poems embedded in string and wire; a virtual reality that gave the entire experience a surrealist atmosphere.

The obvious integrity of each piece and their obvious posthuman, postorganic nature shatters the language and categories so fundamental to western knowledge: life and nonlife, organic and inorganic, the self-mover and the moved. What is integrity if it is no longer defined as “the condition of not being marred or violated; unimpaired or uncorrupted condition; original perfect state; soundness”12?

Creuzet’s Palais de Tokyo show was as much a sonic experience as a visual one.

Not that written language was absent. Around the main body of work presented at Palais de Tokyo were benches made of industrial pine with words etched into them in something like Hoefler font, but I am no typographist. Visitors sitting on them or resting their bags and cameras there obscured some of the words. The benches were meant to have a dual purpose: to allow people to sit and comprehend the entirety of the works both within the wooden pen and on the walls as well as to be part of the art installation. The words etched into the wood were genealogically dispersed and unsparing, seemingly semantically self-evident and ultimately, for me, undecidable. Pinta—a spot or marking in Spanish, but also meaning outrageous and imprudent, and also a human skin disease from spirochete, indistinguishable from the organism that causes syphilis and brought to the Americas in the Spanish invasion. Capitaine—A French military designation and another name for the Nile perch. Aquart—which I took as a poetics of the oceans. Paul Lemerle—which I was hoping might be referring to Félix Lemerle, the jazz guitarist who wrote “Blues for the End of Time,” but even better probably refers to Paul Lemerle, the French Byzantist. Pearl—both the history of enslaved pearl dividing in the Caribbean and the largest recorded nonviolent escape attempt in the Americas and the viscous rioting by pro-slavery whites in its wake.

On the face of it, some of the references seemed to claim their meaning clearly. Clotilda—a schooner which was the last known slave ship to bring captives from Africa to the US arriving in Mobile Bay in 1859 with 110-160 enslaves west African men, women and children. Erika— the massive tropical storm that hit the Caribbean in the early fall, 2015.

But what kind of integrity do these terms have, when thought of as things, and things thought of as kinds of beings always in the process of becoming, whose entrails are inside and outside themselves? If the sculptures are the internal organs of the exhibit and the planks the exhibit’s skin, then this skin is sweating out half-digested truths. When was the last slave ship? Is it wrong to say black slavery remains, Martinican slavery remains? Surely it is not correct to suggest such. So maybe we need a new vocabulary of things. What is the name and form of the ship that reverses the direction of transit but keeps in place the racial logics of labor capture?

What lies between La France as an ideal of freedom for all humans and its history of intervention in the Black Caribbean?

Creuzet’s sound pieces work in a hypnotic middle zone between sense and affect.

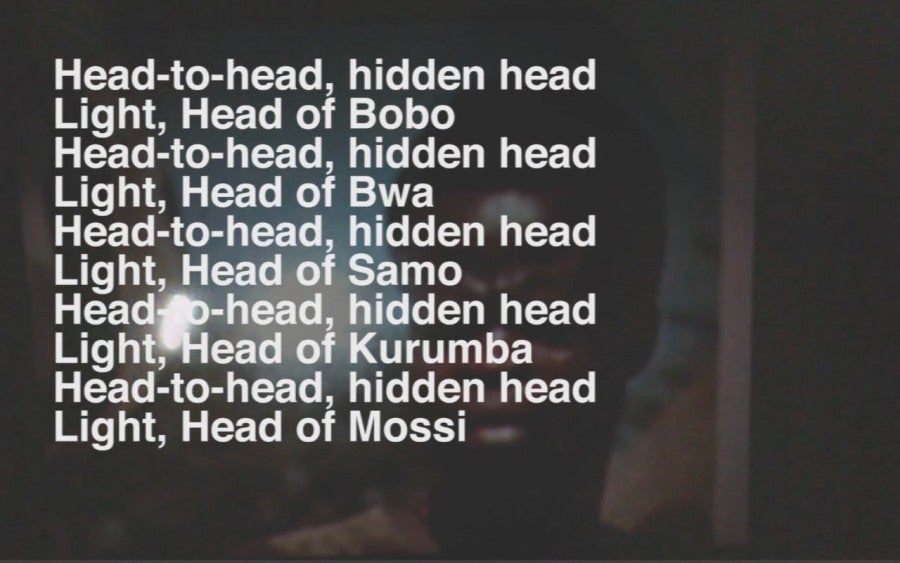

Like his approach to language, much of Creuzet’s sound pieces work in a hypnotic middle zone between sense and affect. His video piece in the black box at Palais de Tokyo was exemplary of this middle zone. A montage of images from an encyclopedia on traditions and customs in Africa, the film was quintessential Creuzet if one can use that adjective in relation to such a young artist. The camera moves over ethnographic images, its spotlight on distorting in order to reveal the colonial undercurrents of this form of artistic capture. These images are interlaid with electro-dance music scenes producing a poetics of catalogued remembrance and amnesia. One image has the shadow of a hand moving across the ethnic credits of a photo, the technocolor stripes of old film reels in the background. And over it all, a sort of genealogy of the hidden and revealed:

Head-to-head, hidden head

Light, Head of Songhay

Head-to-head, hidden head

Light, Head of Jerma

Head-to-head, hidden head

Light, Head of Hausa

Head-to-head, hidden head

Light, Head of Moors13.

“I was interested in what people in these pictures did on the weekend or during a normal day. And I was interested in the relation of movement and cleansing—like you clean dust off a print machine to get a clear image, dance, moving the body, cleans it, makes it healthy for a new kind of fertility, of history.”

I have already begun to slide to the second significance to how Creuzet is writing Caribbean politics, theory, and aesthetics into contemporary geolocalities, namely, a form of temporality at work in his visual and sonic practice that is rewriting an immersive sensory understanding with past and future becomings. As for the coming end of times, Creuzet joins numerous other artists insisting that for the wretched of the earth, the end has come and returned and returned again multiple times. Here the specificities of Creuzet’s genealogy fold in and out of a specific politics and aesthetics of the posthuman. The posthuman has been roaming the earth for a long time. Listen to Ogoni Ken Saro-Wiwo’s struggle against the cold, cruel disaster of the political-economic pact made between Royal Dutch Shell and the Nigerian state. Listen to his daughter, Zina Saro-Wiwa, as she artistically explores the neocolonial conditions of contemporary food economies and politics14. Listen to Will Wilson, Diné photographer who spent early years in Navajo Nation, and who examines in his work the material psychic extimate legacies of nuclear tests and infrastructures. In his words, “a series of artworks entitled Auto Immune Response, which takes as its subject the quixotic relationship between a post-apocalyptic Diné (Navajo) man and the devastatingly beautiful, but toxic environment he inhabits.”15

We sat in his studio, listening to various sound compositions among the tentative sculptural beings and the piles of scavenged materials that might become an internal component of them, if, as Creuzet notes, they survive at all.

“I am not sure if I’ll keep working on a couple of these or take them apart again.”

I didn’t feel I was looking and listening to metaphors of time, human history, Caribbean history so much as I was within the actual, though fictional, environment in which some humans more than others are already part plastic, string, wire, embedded video clips, and scribbled half- clear images. A melancholic jouissance filled the space, neither apocalyptic nor redemptive. Simply there. Simply true. No less political for it.

Titled les lumières affaiblies des étoiles lointaines les lumières à LED des gyrophares se complaisent, lampadaire braise brûle les ailes, sacrifice fou du papillon de lumière, fantôme crépusculaire d’avant la naissance du monde (…)

c’est l’étrange, j’ai dû partir trop longtemps le lointain, mon chez moi est dans mes rêves-noirs c’est l’étrange, des mots étranglés dans la noyade, j’ai hurlé seul dans l’eau, ma fièvre (...) the exhibition was presented from 20/02 to 12/05/2019.

Aimé Césaire, Une Tempête (A Tempest). Édition du Seuil: Paris, 1969.

Jacques Lacan. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan: The Ethics of Psychoanalysis. Translated by Dennis Porter. W.W. Norton & Company: New York, 1997, p. 71.

Édouard Glissant. Poetics of Relation. Translated by Betsy Wing. University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, 1997.

Famously embodied in Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated by Brian Massumi. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 1987.

Glissant, Poetics of Relation, 12.

Glissant, Poetics of Relation, 12.

Glissant, Poetics of Relation, 14.

The entire quote: “I admit that it is a good thing to place different civilizations in contact with each other; that it is an excellent thing to blend different worlds; that whatever its own particular genius may be, a civilization that withdraws into itself atrophies; that for civilizations, exchange is oxygen; that the great good fortune of Europe is to have been a crossroads, and that because it was the locus of all ideas, the receptacle of all philosophies, the meeting place of all sentiments, it was the best center for the redistribution of energy. But then I ask the following question: has colonization really placed civilizations in contact? Or, if you prefer, of all the ways of establishing contact, was it the best? I answer no.” Aimé Césaire. Discourse on Colonialism. Translated by Joan Pinkham. Monthly Review Press, New York, 2001, p. 33.

See Emigration from the French Caribbean: the Origins of an Organized Migration by Stéphanie A. Condon and Philip E. Ogden. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 15.4.1991:505-523.

Vanessa Agard-Jones. Spray. Commonplaces: Itemizing the Technological Present, Somatosphere, May 2014.

Oxford English Dictionary, Second Edition 1989.

Julien Creuzet, Head-to-head, hidden head, Light, 2017.

Nomusa Makhuby, “The Poetics of Entanglement in Zina Saro-Wiwa’s Food Interventions.” Third Text 32.2018:176-199.