« Orestes: Tell me ladies, did we get the right directions? Are we on the right road? Is this the place?

Chorus: What place? What do you want? »1 – Electra, Sophocles

I half expected them to come alive, standing up from their little cardboard stools to greet me like a friend.

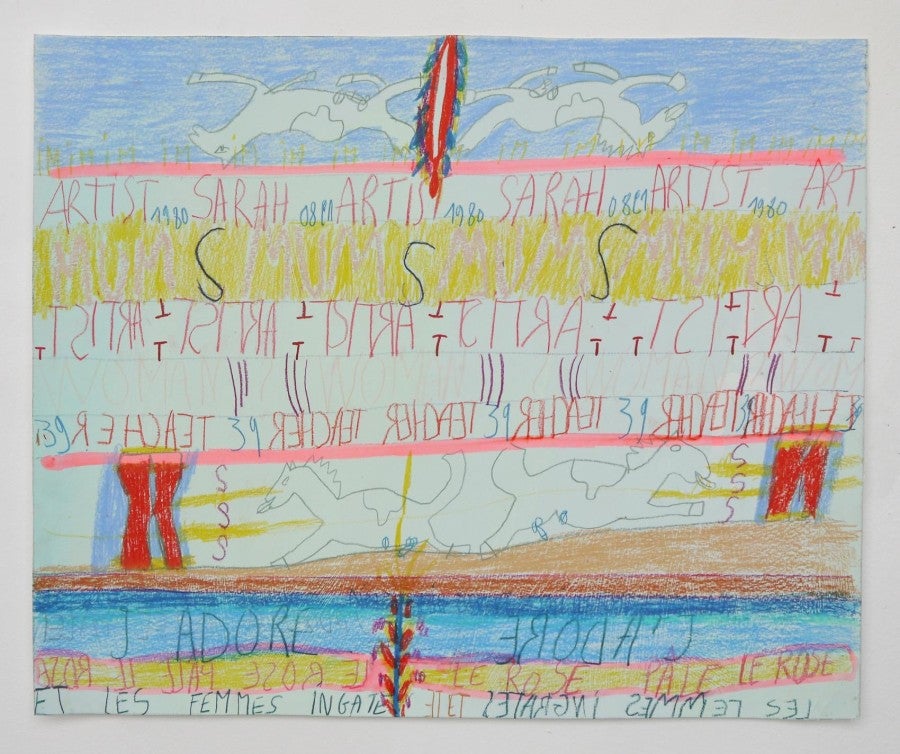

On my last visit to Paris a year ago, I was struck by a set of five headless puppets. The series, entitled TRISTZ INSTITUTT, was hanging from the ceiling of Le Crédac’s main gallery, as part of the group show J’aime le rose pâle et les femmes ingrates2. Curated by Sarah Tritz, the exhibition featured an assembly of her own and hand-picked peers’ work from different contexts—from high profile contemporary artists like Maria Lassnig to remarkable ‘outsiders’ like Paul End—in an idiosyncratic spatial arrangement. “The Institutt is my studio, a place where the sparseness of means brings me total independence”, she later revealed in the curatorial text.

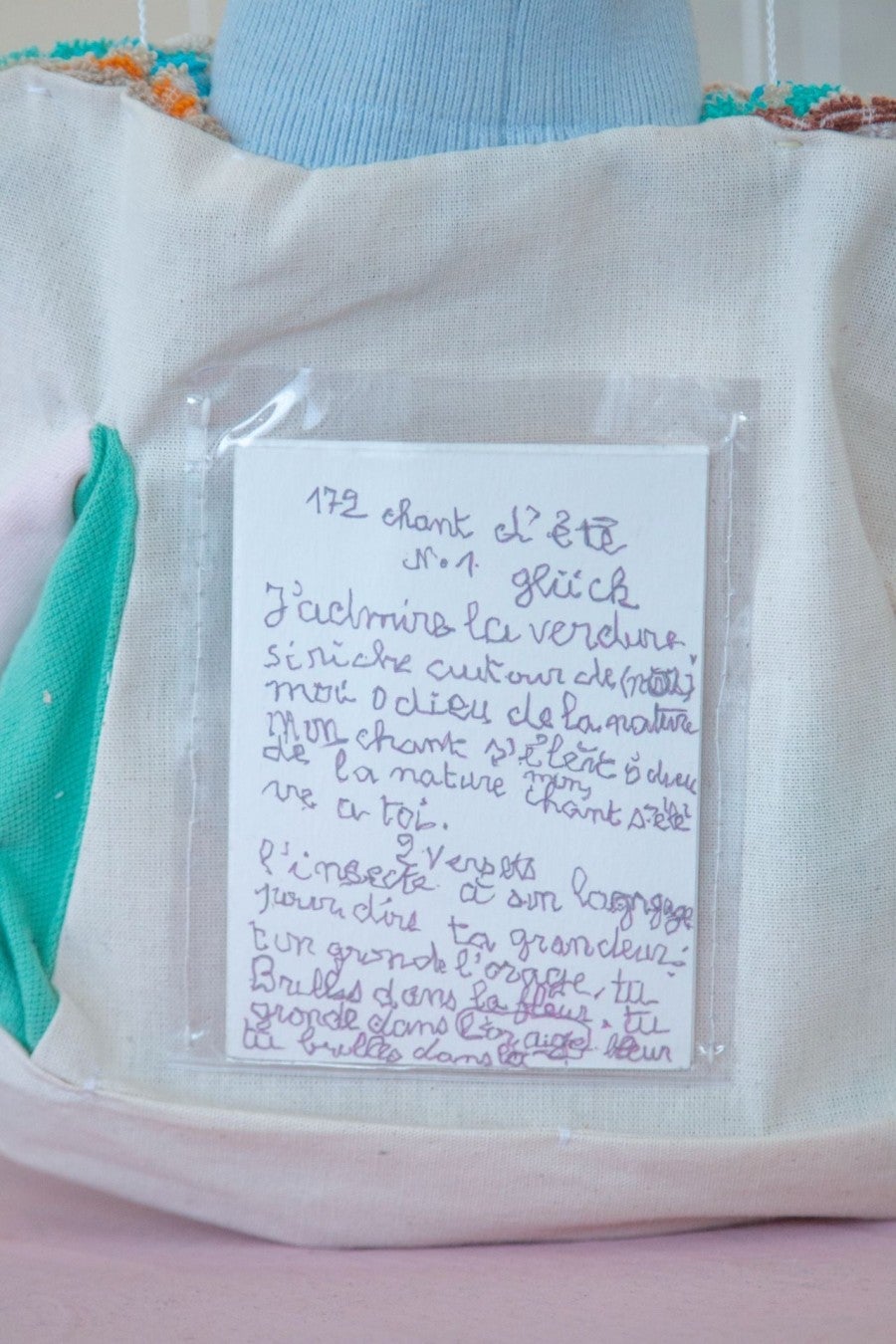

This was the first time I saw Tritz’s work up close and I was immediately taken with those small, clumsy hanging figures. It was a very strange feeling: I had an immediate urge to know their names. Not to read the work titles on the exhibition map, but to call them by their names, as if they could speak up and introduce themselves. On their hand-sewn, pastel-colored turtleneck sweaters, some puppets carried barely legible scribbled notes while others held miniature pendant versions of artworks featured in the group show, like lucky charms. I half expected them to come alive, standing up from their little cardboard stools to greet me like a friend. But they were too tired or too self-enclosed to play host. “Go ahead and see the show for yourself”, their absent mouths seemed to mumble, and I humbly took their advice.

Tritz’s self-implicating imagination was all over the exhibition. “Madame Bovary, c’est moi”, Flaubert famously said. With this in mind, I walked around in search of nonverbal clues about the artist I was planning to profile on this very text. I enjoyed thinking of the threads that brought these works together and tried to guess which were the works made by Tritz. While strolling through the space, I came to realize that my playful approach was in tune with her disregard to conventional connections. If there is a narrative in the show, it appears in piecemeal, without the perception of continuity. There are no phrases. Something happens here, then there, and so on, and together the works create an atmosphere rather than a plot. Tritz’s matchmaking strategies pursue, as is often the case in her own work, the entanglement of erotic and cognitive pleasure. The pairing of Liz Craft’s Me Princess (2008-13) with Tritz’s Pulpe Espace (2017), for example, is pure joy, the pieces seem like lifetime bedfellows. Craft’s pinkish (pâle-rose) wacky figure is modeled by hand and bears a rough and hard to explain sensuality, highlighted by the shiny enamel of Tritz’s wall-piece like a sassy magnifying mirror.

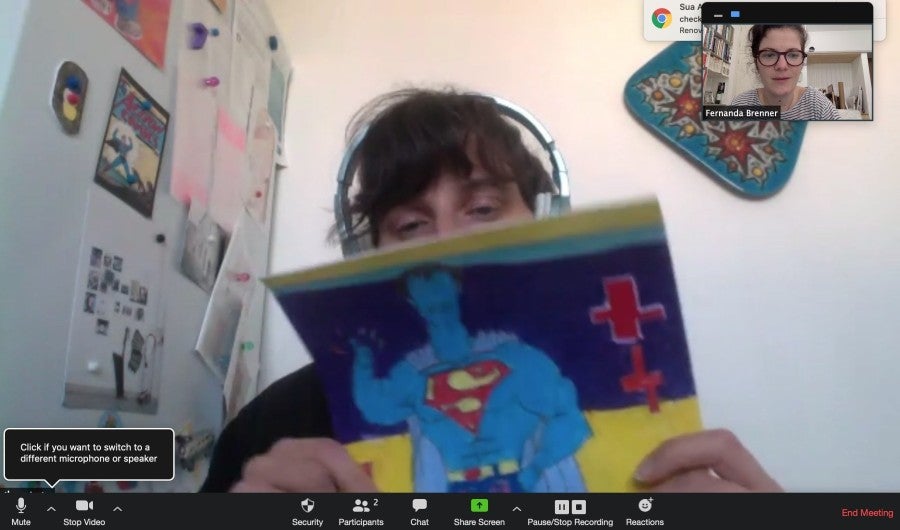

My visit to Le Crédac was supposed to be followed by a visit to the artist’s studio a few months later, but—as with every meeting scheduled during the COVID-19 pandemic—it turned into an online conversation and long email threads. As we talked, I couldn’t avoid matching the “headshot version” of the artist on my screen with the bulky, headless bodies I had physically encountered in Ivry-sur-Seine, as in an exquisite corpse game. During our call, Tritz wore big metallic blue headphones and a tall pony-tail, her cool and almost cartoonish appearance was surrounded by paper scraps and photos held by magnets. It was unclear to me if those were project sketches, references or doodles made by her young son; perhaps all of that combined. From my distanced standpoint, it seems that her personal universe and her work inform each other, not in a strictly biographical but in a visual and affective way. This odd situation, of not meeting Tritz in person but developing a quirky emotional bond with her works I saw live, left me with a sort of out-of-sync perception of her practice, in which all the boundaries between online and physical presence, creator and creature, intimacy and self-consciousness, space and time were suddenly blurred. It was as if I turned myself into one of the Tristz Institutt’s inmates.

Friends with Benefits

This fleeting perception of what is real, reminds me of Luigi Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author. In this early-modernist play, the Italian dramatist describes an eerie situation in which he, as author, is confronted with a disgruntled group of characters—a family of six—and their misfortune. The play unfolds from the encounter between the family, a crew of actors and a director in a rehearsal room. In the preface of the 1921 edition of this metalinguistic saga, Pirandello states that he can’t explain why these characters appeared to him or how they were « born alive”, knowing only that they craved for life and identified him as the one that should fulfill their demand. Instead of shaping the characters’ personalities in accordance with pre-established narratives or allegorical purposes, Pirandello was faced with a hierarchical twist when the self-righteous family appeared: this time, the characters shaped the play and not the other way around, and this makeshift situation left him with no choice but to put them on stage and to see what would happen.To elaborate on his plight, Pirandello mentions the “nimble little maidservant” with whom he says to have a long and bittersweet relationship: Fantasy.

Like the family members brought to Pirandello by his whimsical servant, Sarah Tritz’s anthropomorphic figures don’t rely on narrative support to stand still. For that matter, I would say that other than a dramatist, she is a sculptor of characters. Unlike Pirandello, Tritz seems to be at all times in good terms with Miss Fantasy, as she isn’t trying to hold her captive or tame her. The two of them are more like ‘friends with benefits’ that can easily navigate between dirty and small talk and cannot be bothered by the emotional turmoils brought by existencial quests or, in other words, by the fiction versus real-life conundrum that haunts the participants of the Italian play. On the contrary: Tritz is interested in flatness, in one-dimensional characters that are what they are, which becomes a delightful paradox when we talk about sculpture. Her characteristic, straightforward humour and deadpan style can be best observed in her more cartoonish figures like the short-legged and not-so-happy smiley Emoticon (2015) and the severed head and legs of Sluggo (2015), borrowed from an American comic from the 1930s and tweaked by Tritz for her solo show at Fondation d’entreprise Ricard in 2015.

Sluggo’s genealogy traces back to what curator Claire Moulène called the “mystery guests”3 of Tritz’s practice, alluding to her myriad references and the cultural markers of art history that often offer a starting point for new work, or offer ways out of formal impasses, as the artist puts it. I later found out that Tristz Institutt’s puppets were given monikers: Nicole, Ode, CATHY, JILL and Rainn-Gene4, confirming my initial intuition that, instead of naming them with regular artwork titles, they were baptized. While a great number of Tritz’s previous works have famous godparents and cultural ballasts, the puppets stand for themselves. Phrases don’t catch them, theories don’t hold them, they have no practical use. Like Pirandello’s characters, the Institutt’s inmates are trapped in the parallel time of the studio and in their own mindsets.

...a banal action which becomes political here insofar as it determines access to and between bodies.

Sarah Tritz’s figures from the past two years have simpler features and at the same time are more enigmatic. Their nonchalant and self-enclosed presence in the exhibition rooms make up for the eschewal of a plot; their given titles—or names—are the only tip we ever get. Elle (2019), a wooden casket-like faceless women’s bust, for instance, holds a secret. Elle is both a first name in English and a personal pronoun in French that means ‘she’. A small doorknob is found on the back of her head. To access Elle’s inner content, the public must peek in at their own risk, there’s no official permission to ‘activate the work’. I did it. Cracking her open made me feel as if I was swept in too close, and my own red sides were exposed, or worse, it was like catching your parents having sex. It was a quick transgression but gave me enough time to spot the rough line drawing of a copulating couple living inside that big wooden head. The twosome looked stiff and schematic as if it was engaged in perpetual intercourse. Their bodies were underscored by a child-like scribble reading: MIAMAIMIAM—the juiciest onomatopoeia of them all—lending the drawing a claustrophobic and dizzying straightforwardness. To a slightly naughty mind, the sheer pairing of the words elle + casket + secret door-knob would be enough to create a mysteriously sensual atmosphere, but Tritz leaves no room for foreplay. Elle’s flirtatious mood vanishes as soon as we pull the door-knob, as if turning on a white fluorescent lamp in a dark and sweaty dance floor. The work is indeed a vessel meant to be opened and closed—a banal action which becomes political here insofar as it determines access to and between bodies. I would hesitate to invoke penetration, but Tritz herself deploys the term, moving away from the hermeneutics of eroticism when talking about her work’s undeniable sexual presence: “I’m convinced of the link between learning to write in capitals and the origin of eroticism in children. It is taking possession of writing and then language like one takes possession of another’s body or of pleasure”5, Tritz says. Her meager means of production and the raw approach Tritz employs in some of her most recent work square up to the most primitive libido, placing her work in the gap between a babble and a recognizable word.

Applied Briécologie or Language is a (computer) Virus6

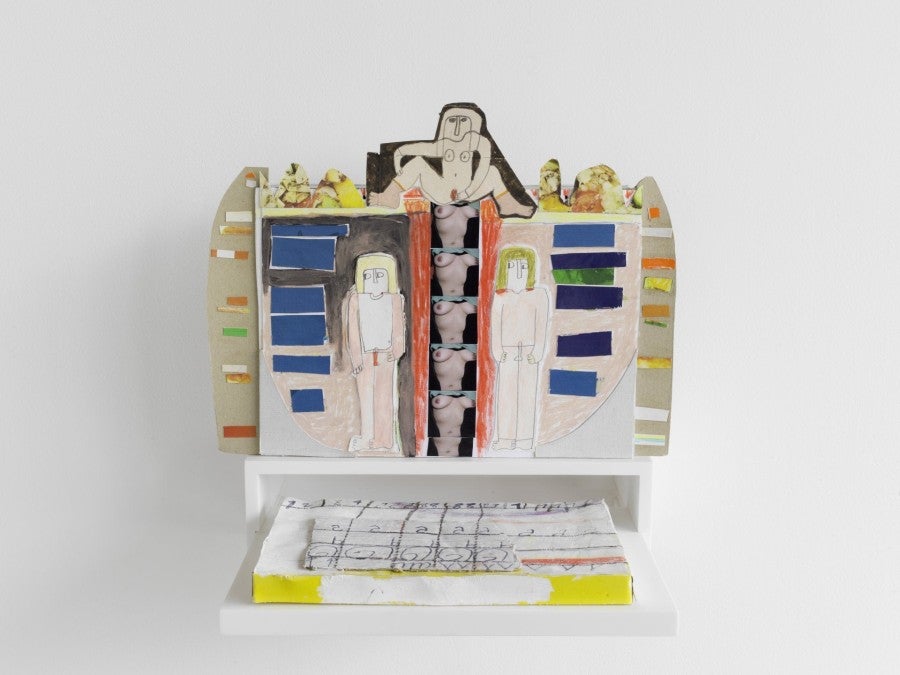

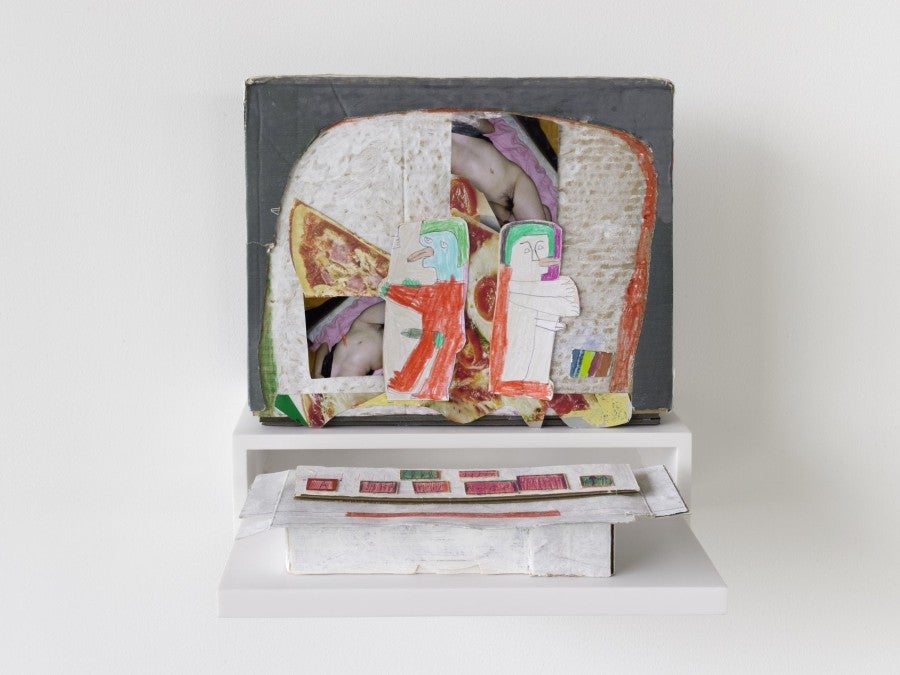

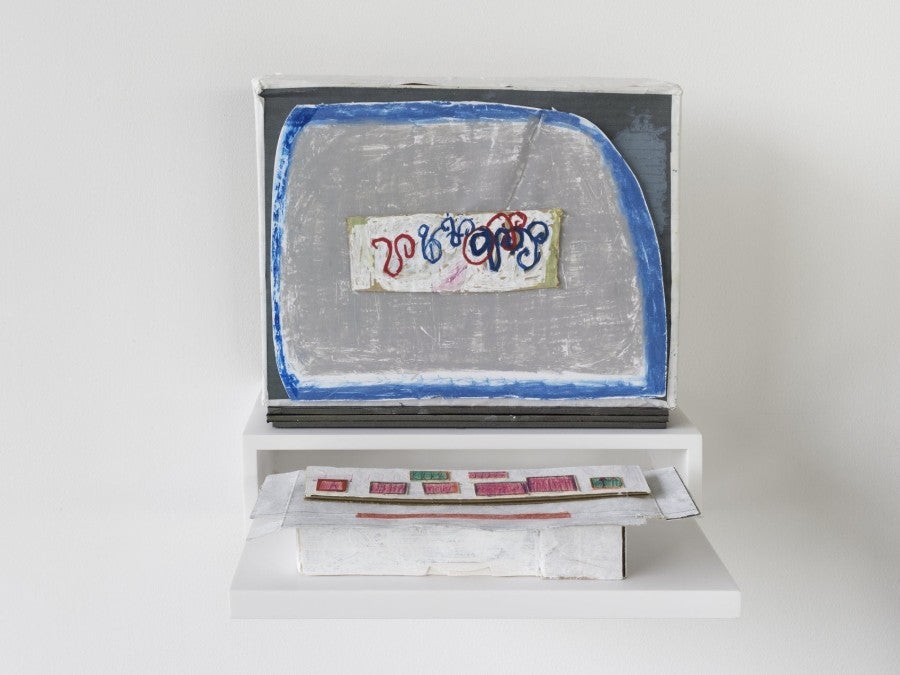

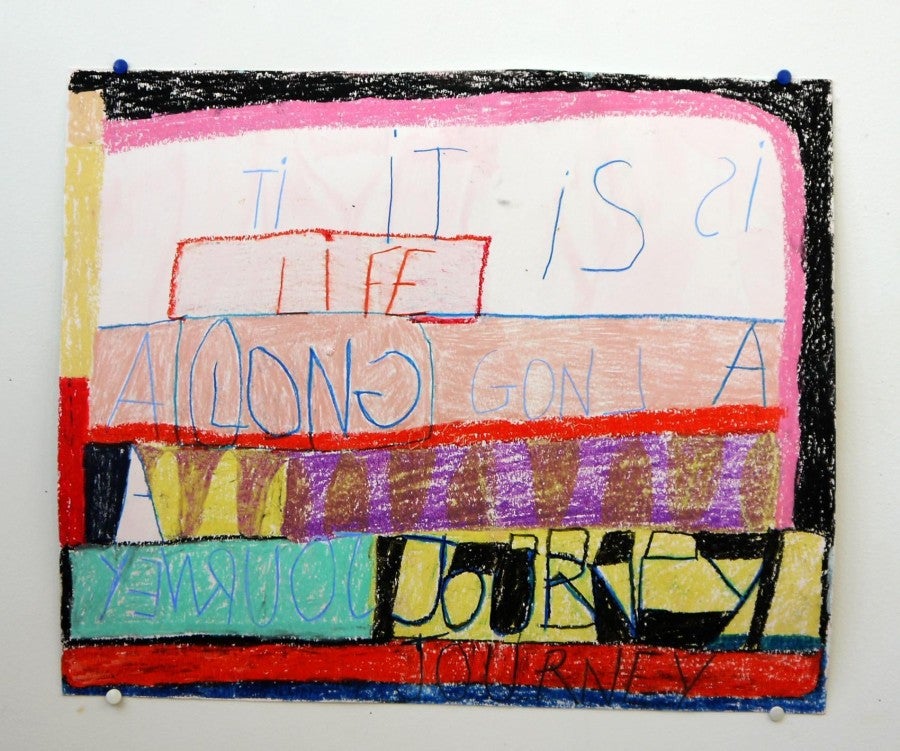

Language and desire are in fact a complicated mix when it comes to human interaction. People are constantly sheltering themselves under the umbrellas of their limited language, and their world is written on the undersides of these caps7. Desire, instead, opens multiple ambiguous pathways to meaning and misunderstanding. Just add a dose of uncouthness to that muddle and you get the Theater Computer series (2019). Made from leftover packaging cut-outs and doodles—“briécologie” as Tritz puts it—these anti-tech juxtapositions bend kindergarten aesthetic choices into acid social commentary. The cardboard screens are ‘on’: ‘playing’ a never-ending loop with unexpected explicit content, as if it was left behind by some random pervert who forgot to log-out from a public computer. On one of the computers we see an adroitly positioned pizza slice melting into a bare crotch that leads to the prescriptive portmanteau title of the piece: Pizsex Lèche (2019). Pizza-plus-sex-plus-lick equals fast-track satisfaction, final stop. Tritz’s keyboards don’t have enough characters to structure intelligible sentences or to ignite the search engine that leads one to the broad and easily accessible planet of online pornography. We have no agency over the content provided to us by the artist, like television in the 90s. This change of pace prompted by online communication/interaction had a massive impact on the way we communicate and perceive reality and physicality. To be online is to be immersed in a never-ending scroll of content; a continuum with no catharsis, and to craft—and control—a persona, however much it resembles (or not) one’s ‘in-real-life’ self.

I have a strange feeling that Sarah Tritz’s anti-utilitarian dysfunctional computers might hold the crack-code to something ominous and deadly earnest: the future.

As I said before, Sarah Tritz is a sculptor of characters, not avatars. Her self-implicating presence—more subliminal in other works—takes the forefront in the Theater Computer series. The fragmented naked bodies we see are actually homemade, crude snapshots of the artist’s most intimate parts, deliberately scrambling the roles of the exhibitionist and the voyeur, or the consumer and the producer of visual content. What matters here is the box, the whole computer, there is no hierarchy between her own image, appropriated content and the packaging cutouts.

“Make-Believe! Reality! Oh, to hell with the lot of you! Lights! Lights!”8, the Director shouts at the characters and actors, all gathered on stage in the final pages of Pirandello’s play. In times when ten billion fingers are fumbling away, anxiously typing WhatsApp messages, taking selfies and tweeting their minds, the author’s obsession with the making of identity and personality, multiple viewpoints and the relativity of truth is very up-to-date. In other words: we understand less and less about the mechanics of the world as these powerful technologies assume more control over our everyday lives and our own psychology. Is there a way out? Lights to be turned on? I have a strange feeling that Sarah Tritz’s anti-utilitarian dysfunctional computers might hold the crack-code to something ominous and deadly earnest: the future.

“Of Bodies Changed to Other Forms I tell”9

When I met Sarah Tritz digitally a few months ago, she told me about the drawings she was working on while self-isolating with her family, and more specifically about the “jackets” (My Jacket #1 YOU/UOY and My Jacket #2 My Nose/Your Nose, both 2020). Like Tritz’s most recent experiments in ‘briécologie’—i.e the Theatre Computer series or Le Train Rouge (2019)—, the jackets might have an eccentric DIY feeling, but are in no way naive. By the time we spoke, she was collecting all sorts of packaging and stationery that passed through her hands. In the garments made by the artist (referring also to Tristz Institutt inmates’ little suits), memories and personal references are like scraps fished out of the shredder and—along with the leftover cardboard and textile patches—reassembled into mad-house couture. I recall that I was wearing flannel pajama pants—as I had been doing indiscriminately for way too long—when Tritz showed me her work in progress through the screen and the exquisite-corpse game suddenly reemerged in my head. This time I couldn’t avoid mentally matching my dull and somewhat embarrassing home-wear with the fabulous papercut jackets she was showing me. This fun pastime took me straight to a Rei Kawakubo catwalk. The renowned Japanese designer has always fascinated me. Her approach to clothes-making is the result of an insistent questioning around how to be a woman in the world, rather than following a trend-oriented fashion. Like Tritz’s jackets, the wearability of Kawakubo’s catwalk garments is not the point. For over four decades, the designer has been pursuing a kind of beauty that is free from the clichéd ideas of sexuality, good taste, and other constructed norms. Kawakubo’s mischievous oversized tear-down sweaters, inspired by the Buddhist concept wabi-sabi10, and lumps-and-bumps getups (thinking about her iconic ‘Body meets dress, Dress meets body’ collection and the costumes for Merce Cunningham’s Scenario, both from 1997) exist within and between dualities—whether self and other, object and subject, art and fashion, East and West.

...all Tritz works share a rough sense of humour and an often malicious approach to corporeality and its representations.

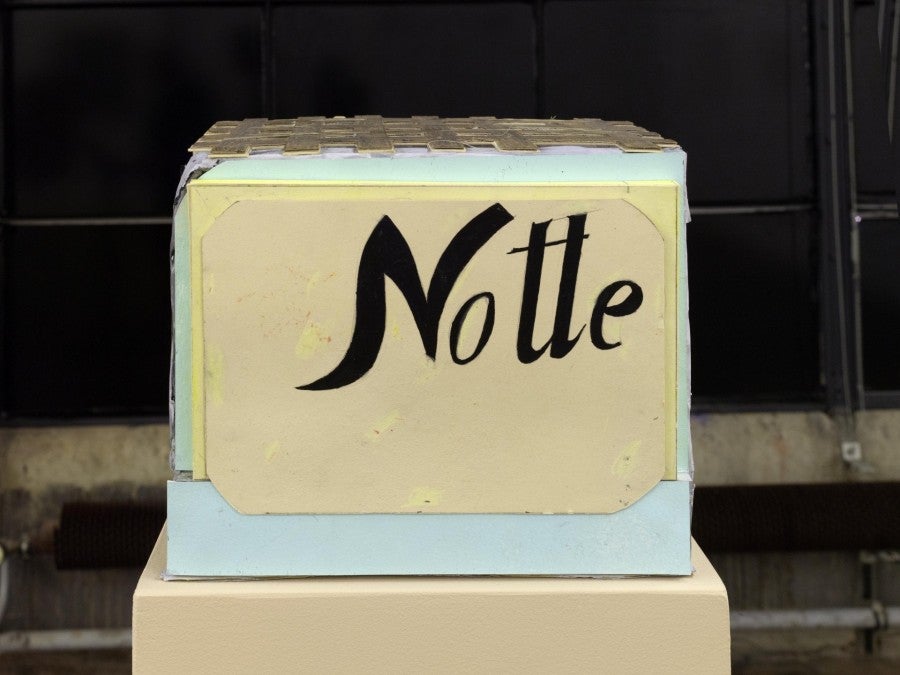

Since she started working professionally fifteen years ago, Sarah Tritz has been playing with multiple standpoints, myriad references and advocating for the hybrid in her work. Following a similar path than Kawakubo’s to shape her ‘body-stories’, Tritz combines sometimes sophisticated and complex materials and techniques that require external assistance, like bronze and structured aluminium, with other materials with more humble origins and that can be easily manipulated, like cardboard and multicolored markers. Regardless of their size, media and the complexity of their making, all Tritz works share a rough sense of humour and an often malicious approach to corporeality and its representations. For years, she has been pursuing—in her own and in other’s work—the many possible answers to the question of what a body is and what a body can do. In Tritz universe, what might look like simple resourcefulness or the product of self-taught spontaneity is often the outcome of her eclectic, surgically picked and irreverently assembled repertoire; from childhood memories in Parisian suburbs to elements from art and design. Her sources range from Art deco furniture (in works like Mon Buffet (2019)), to Jannis Kounellis’s typography (referenced in Notte, 2017), passing through Egyptian grave treasures, the 1930’s women-shaped bronze door knobs of Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris and her teaching experience at École nationale supérieure des Arts Décoratifs.

While Tritz is invariably full-frontal in her practice, she doesn’t set out to persuade viewers to suspend their disbelief but instead to introduce a measure of reverie into daily life. Every character created by Tritz is also a more or less explicit commentary on reality as well as a projection of who she wants to be at that point. Dorothée (2014), for example, somehow personifies the friction between Paris’ glamourous bourgeois past and the often brutal reality of its contemporary multicultural version. In Tritz’s words: Dorothée is a young girl with messy hair who loves necklaces. She is homeless but she stands proud on a fancy pedestal, made of oak and colored plexiglas. Made out of a porcelain vase decorated with paintings and necklaces, and blonde, matted hair tied with brass wire, Dorothée could be an aristocrat and an anarchist, someone who has lost her money and her freedom but who hasn’t lost her nobility.

Whenever someone slips their arms through the non-existing arm-holes of a Rei Kawakubo’s garment, they start walking hand-in-hand with the person who created it. Likewise, Tritz’s character-sculptures embody a fleeting sense of intimacy shared between viewer and author, their humble materiality and self-assuring presence is inviting but treacherous at the same time. You cannot wear those clothes and see those works and walk the same way, they make you aware of your own body and the place it occupies in public space. Like Dorothée or Paris, we all have many versions of ourselves but some things never change. You can choose to be an anarchist, but never an aristocrat.

The Body as a Cracked Vessel

While we were speaking about the aforementioned unfathomable question of what a body is and can do, Tritz brought Barbara Hammer’s work to the conversation. The American artist’s pioneer approach to the queer body in the experimental erotic films she made in the 70s is outstanding, as Hammer notices herself: “I was lucky when I made Dyketactics (1974) I didn’t realize that it was the first lesbian film made by a lesbian”11. “Instead, I just burst out and let my energy carry me through my work.” The film drew from footage of naked women in the woods of Northern California, and of the artist having sex with a friend, to create a multilayered frenetic audiovisual collage. To watch Hammer’s films is like following a gymnast performing a floor routine, and I could say something similar of Tritz, whose collages and drawings are guided by her own vitality. She vaults and tumbles materials and ideas in the air and sticks every landing. Both artists lay bare the modus-operandi of their practice, in which the biographical is underscored by conceptual language and entangled imagery from multiple sources unfolds into—more or less explicit—sensuous romps. Sarah Tritz’s practice also meets Hammer’s in its investigation of the relationship between raw sexuality and the origins of language. What Hammer says about her personal energy being the work’s ignition, is to me the perfect entry point to Tritz’s untamed works on paper; which is the utmost result of thorough studio practice with a high-dose of mental agility and improvisation. Revisiting work like Hammer’s—and also Rei Kawakubo’s—in parallel to Tritz’s recent practice is a timely reminder that the body itself and the social conventions around it are something forever unfinished and open to change. These three women—from different generations and contexts—are ultimately questioning notions of what is sexually alluring and what is grotesque, particularly within the imposing Western vocabulary and its corollary.

In the second act of the aforementioned Pirandello play, one of the characters, The Father, prompts a heated argument about the commonsensical use of the word illusion as a vulgar opposition to what is perceived as reality. He claims that men’s reality is fleeting, always ready to reveal itself as illusion, whereas the character’s reality remains fixed in the timeless reality of art. Sarah Tritz told me that the reason the puppets in Tritz Institutt have no heads is that she couldn’t find a way to make them so she just let them be without. I am very keen on the idea of not trying to attach a head on anybody’s neck. At the same time, I also believe that heads can be replaced and amended. I feel this is precisely where we are now, all trapped in a stranger-than-fiction limbo and—like Pirandello’s six—we are being confronted with layers of conflicting stories, while feeling stage fright and craving for a plot-twist.

Sophocles, Electra, translated by Anne Carson, Oxford University Press, 2001, p.146.

J’aime le rose pâle et les femmes ingrates, Centre D’Art Contemporain D’Ivry – Le Crédac, Ivry-sur-Seine, France, 12 August – 15 September 2019.

Moulène, Claire, Diabolo Chews Gum in the Rain and Thinks About Sex, curatorial text for the Fondation d’entreprise Ricard, 2015.

The puppets’ names are references to people: Cathy for Cathy Wilkes; Nicole for Nicole Eisenman; Rainn-Gene is a contraction of Gene Kelly and Singin' in the Rain.

In conversation with the writer, April 2020.

This chapter title is an allusion to Laurie Anderson’s song “Language is a Virus”, 1986 and the word “Briécologie” is a neologism mixing bricolage and écologie.

Franco “Bifo” Berardi, “Breathing: Chaos and Poetry”, Semiotext(e), 2018, p. 48.

Pirandello, Luigi, Six Characters in Search of an Author, translated by Stephen Mulrine. Nick Hern Books, 2003, p.132.

First line of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Book I, which Sarah Tritz quotes in an interview with Sandra Patron and Franck Balland in Sarah Tritz, les presses du réel, 2016.

Wabi-sabi is a traditional ancient aesthetic concept linked to the philosophy of Zen Buddhism that embraces imperfection and pursues beauty in every aspect of fallibility.

From “An Interview with Barbara Hammer”, Wide Angle 20.1 (1998) p. 64-93. Retrieved from barbarahammer.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Kate-Haug_An-Interview-with-Barbara-Hammer-1998.pdf