Ivan Illich, Tools for Conviviality (London: Fontana/Collins, 1975), 33.

Walter Benjamin, The Origin of German Tragic Drama [1928], trans. John Osborne, (London - Verso, 2009)

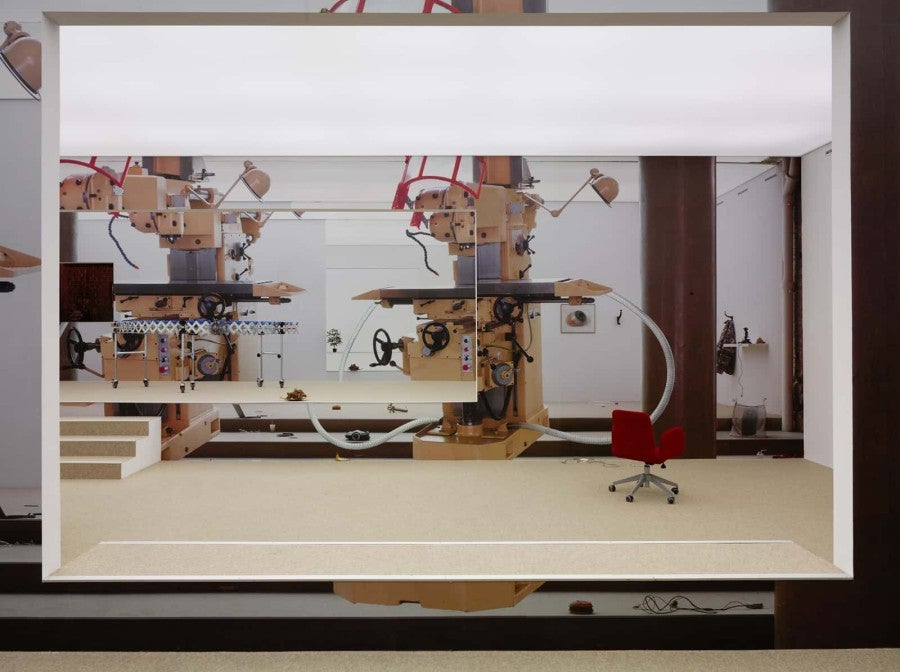

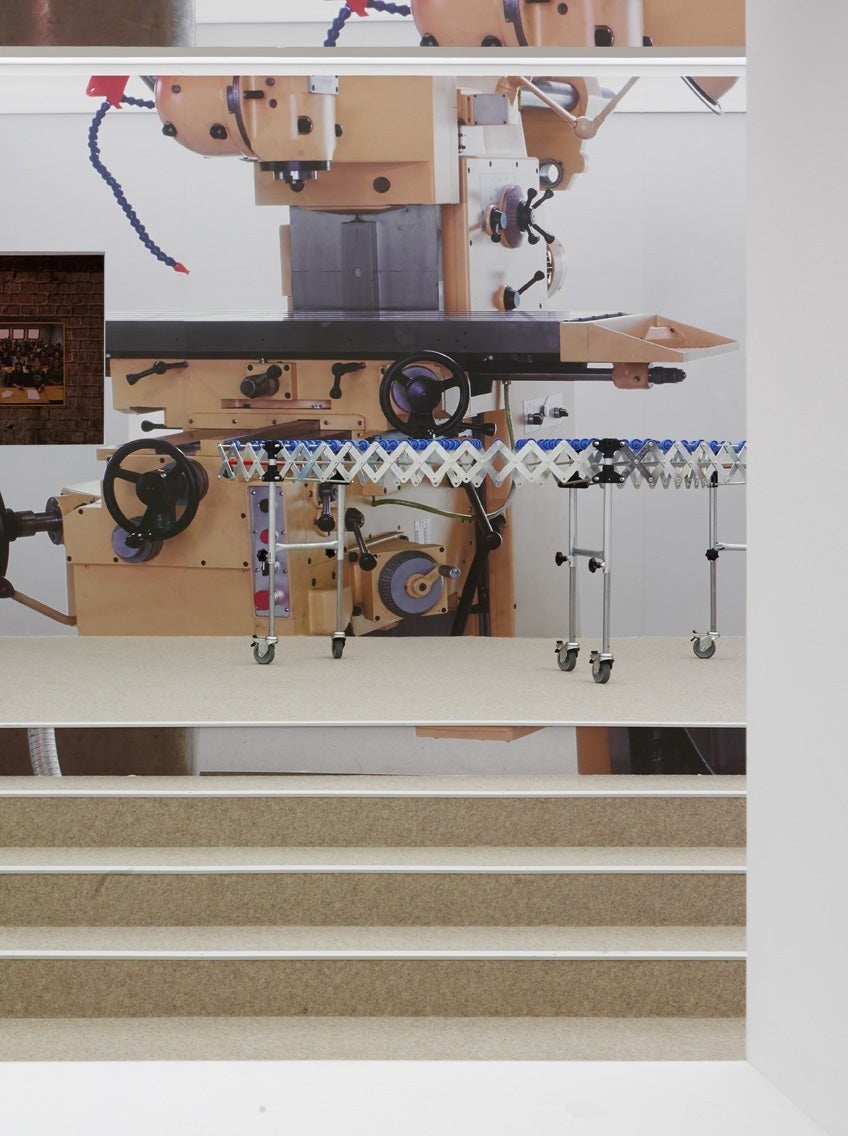

Quoted in Emmanuelle Lainé, Incremental Self (2017), 3-channel video installation, HD video, colour, sound, 20 min.

See ‘Welcome to the Jungle: Working and Struggling in Amazon Warehouses’, AngryWorkersWorld, 20 December 2015, https://angryworkersworld.wordpress.com/2015/12/20/welcome-to-the-jungle-working-and-struggling-in-amazon-warehouses/.

Ibid.

Ibid. For an extensive record of the labour dispute at Amazon in Poznań in 2015, see Ralf Ruckus, ‘Confronting Amazon’, Jacobin, 31 March 2016, https://www.jacobinmag.com/2016/03/amazon-poland-poznan-strikes-workers

Quoted in: Emmanuelle Lainé, Incremental Self (2017) 20 Min, 3 channels installation , H.D. colour and sound video.

See Bruno Latour, ‘The Berlin Key or How to Do Things with Words’, in Matter, Materiality and Modern Culture, ed. P. M. Graves-Brown (London - Routledge, 2000), 10–21.

Andreas Greiert, Erlösung der Geschichte vom Darstellenden. Grundlagen des Geschichtsdenkens bei Walter Benjamin 1915–1925 (Paderborn - Wilhelm Fink, 2011), 241.

Ivan Illich, Selbstbegrenzung: Eine politisch Kritik der Technik, übers. v. Ylva Eriksson-Kuchenbuch, C. H. Beck, München 1998, S. 28

Vgl. Walter Benjamin, „Ursprung des deutschen Trauerspiels“, in: Gesammelte Schriften, Bd. I-1, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1987, S. 337-409.

Zit. in: Emmanuelle Lainé, Incremental Self (2017), Drei-Kanal-Videoinstallation, HD-Video, Farbe, Ton, 20 Min.

Siehe „Welcome to the Jungle: Working and Struggling in Amazon Warehouses“, AngryWorkersWorld, 20.12.2015, https://angryworkersworld.wordpress.com/2015/12/20/welcome-to-the-jungle-working-and-struggling-in-amazon-warehouses/

Zit. in: „Welcome to the Jungle“, ebd.

Ebd. Vgl. auch Ralf Ruckus, „Confronting Amazon“, Jacobin, 31.03.2016, https://www.jacobinmag.com/2016/03/amazon-poland-poznan-strikes-workers

Zit. in: Lainé, Incremental Self, ebd.

Vgl. etwa Bruno Latour, Der Berliner Schlüssel. Erkundungen eines Liebhabers der Wissenschaften, Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1996.

Andreas Greiert, Erlösung der Geschichte vom Darstellenden. Grundlagen des Geschichtsdenkens bei Walter Benjamin 1915–1925, Wilhelm Fink, Paderborn 2011, S. 241.