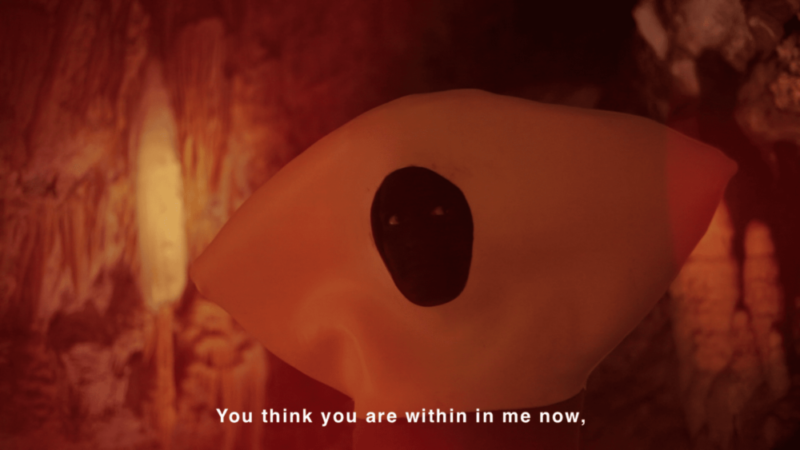

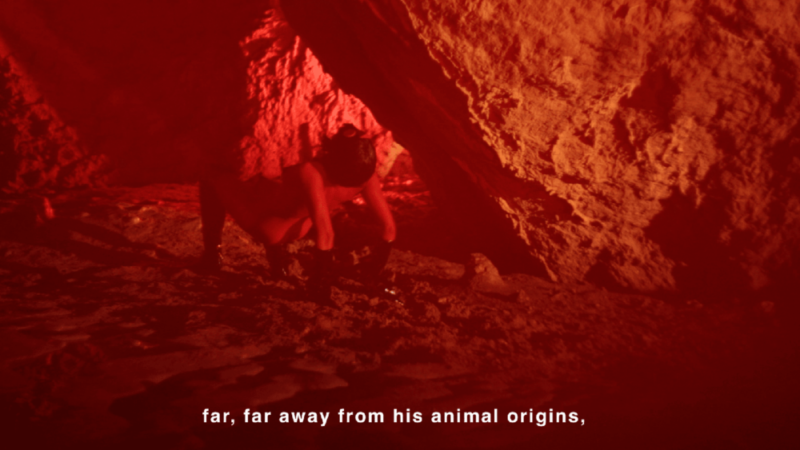

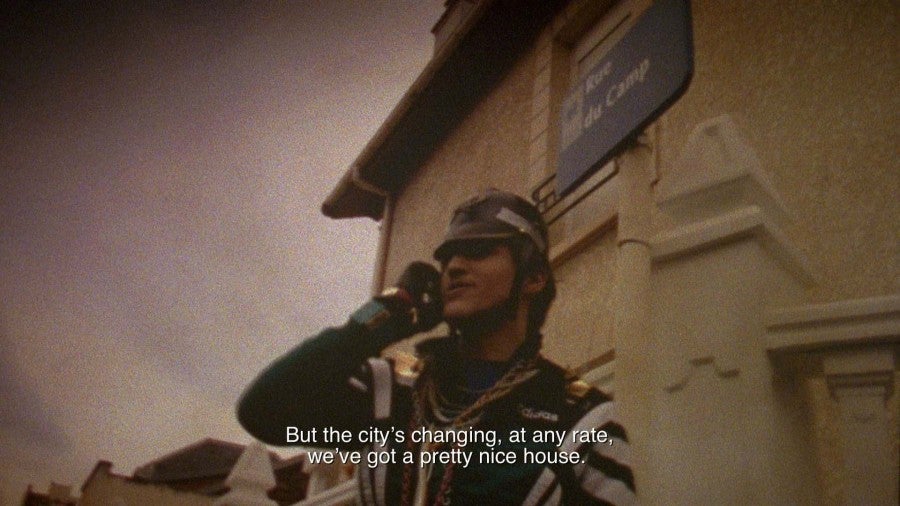

Grotta Profunda, les humeurs du gouffre, 2011. Credits: Cast: Simon Fravega d’Amore, Mickaël Phelippeau, Maeva Cunci, Viviana Moin, Aude Lachaise, Walkind Rodriguez, Tobias Haberkorn / Costume and Set design: Rachel Garcia / Image: Alexis Kavyrchine / Editing: Damien Oliveres / Music: Claire Vailler, Vincent Denieul, Déficits Des Années Antérieures, JADA, Olivier Lapert, J. Strauss. / Co-production: Le Printemps de Septembre, Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Caza d’oro, La Galerie de Noisy-le-Sec / Executive production: Dirty Business of Dreams / Duration: 30 minutes / Language: French with English subtitles

Terry Eagleton, Capitalism as Form, New Left Review #14, March-April 2002, p.119.

Blaise Pascal, Pensées, (Harmondsworth 1966), pp. 46–7, quoted in Terry Eagleton, Capitalism as Form, New Left Review #14, March-April 2002, p.119.

Terry Eagleton, Capitalism as Form, New Left Review #14, March-April 2002, p.119.

Id.

Viola Melon, Baiser Melocoton - a film in a goddess, 2013-14. Credits: Cast: Julia Propos, Clara Pichard / Camera: Pauline Curnier Jardin / Editing: Margaux Parillaud / Sound: Vincent Denieul / Duration: 10 mins / Language: French or English.

Explosion Ma Baby, 2016. Credits: Camera: Pauline Curnier Jardin and Julien Hogert / Editing: Margaux Parillaud / Music and sound design: Vincent Denieul / Drums: Benjamin Colin / Co-production: Le Confort Moderne, Poitiers and the Rijksakademie Van Beeldende Kunsten, Amsterdam / Distribution: EYE Film Institut Netherlands / Duration: 8 minutes 27 secs.

Tom Gunning, The Transforming Image: the Roots of Animation in Metamorphosis and Motion, in Pervasive Animation, ed. by Suzanne Buchan, Routledge, 2013, p. 55.

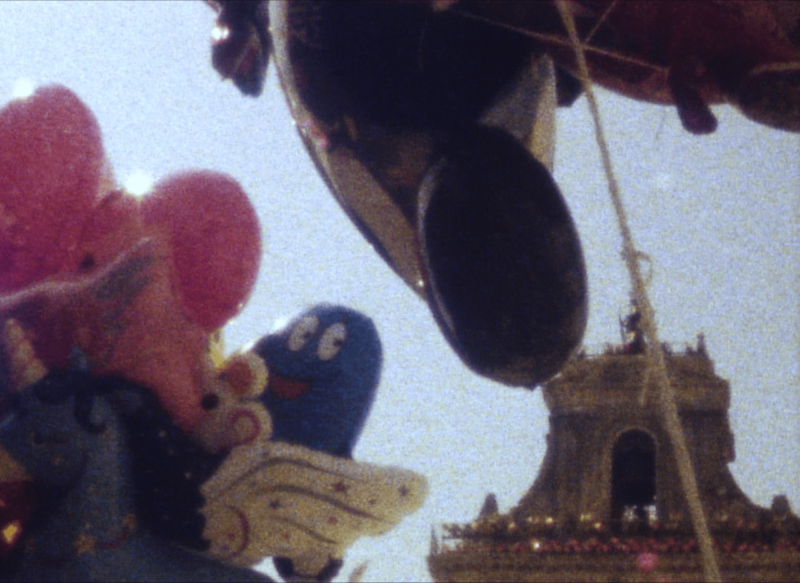

Blutbad Parade, 2014. Credits: Cast: Anne Chaniolleau, Nicolas Chardon, Simon Fravéga d’Amore, Chris Imler, Viola Thiele, and Christian Kell / Costumes and make-up: Rachel Garcia / Image: Alexis Kavyrchine and Victor Zébo / Text: Tobias Haberkorn and Pauline Curnier Jardin / Editing: Julien Gourbeix / Sound editing: Vincent Denieul.

Terry Eagleton, Capitalism as Form, New Left Review #14, March-April 2002, p. 121.

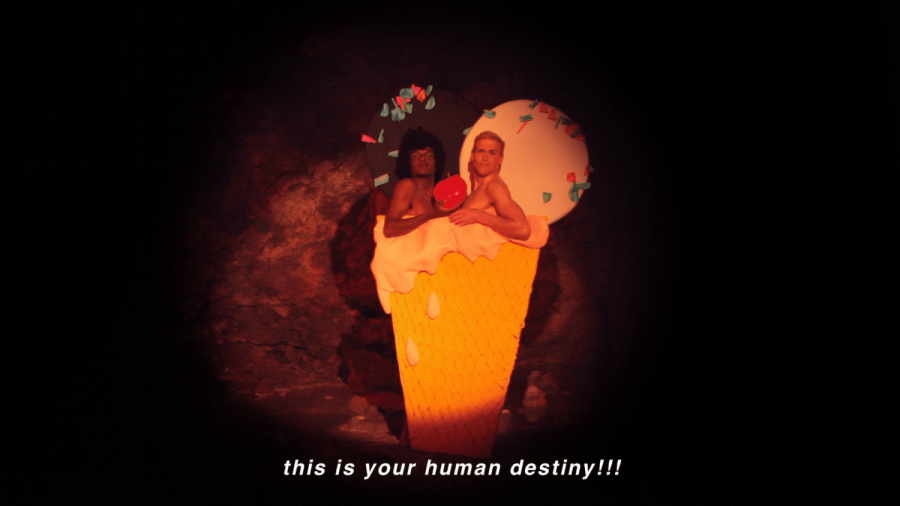

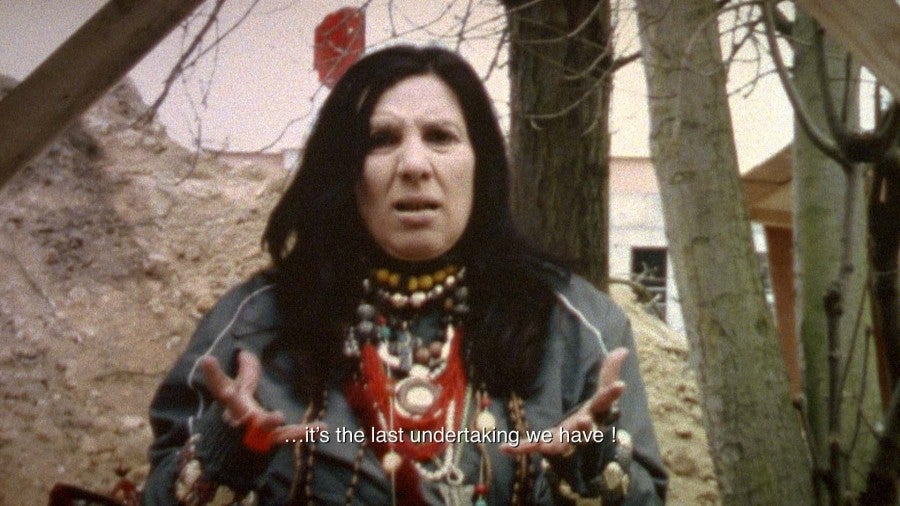

Cœurs de Silex (Hearts of Flint), 2012. Credits: Directed by Pauline Curnier Jardin / Cast: Simon Fravega d'Amore, Viviana Moin, Eric Abrouga, Mia Depret, Marguerite Vappereau and Tobias Haberkorn / Image: Pauline Curnier Jardin and Alexis Kavyrchine / Editing: Maéva Dayras / Sound: Pierre Desprat / Production: La Galerie de Noisy-le-Sec / Duration: 40 minutes / Language: French, German, Spanish, English.

Lauren Berlant, Cruel Optimism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), p. 5.

Ernesto de Martino, Magic a Theory from the South, Hua books (Chicago:2015), p. 85.

See Frank Wilderson, III, Gramsci’s Black Marx: Whither the Slave in Civil Society?, Social Identities, Volume 9, Number 2, 2003.

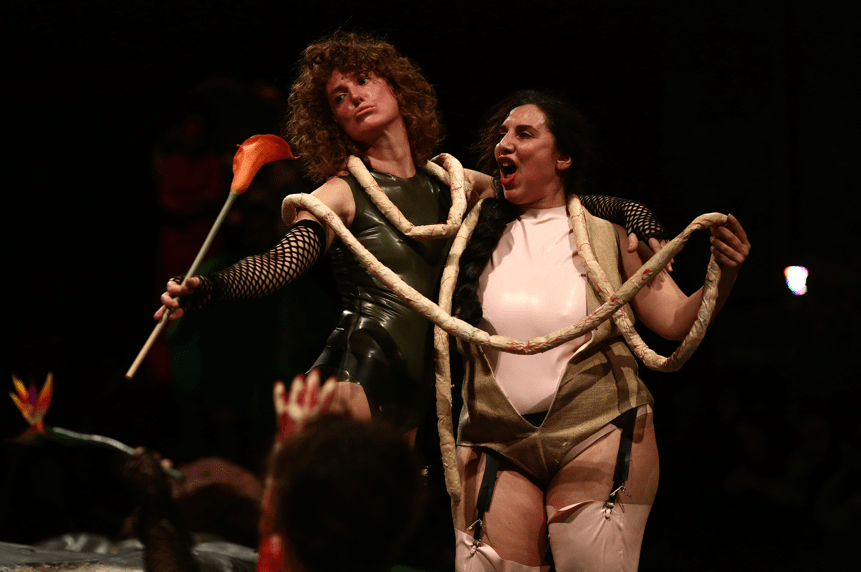

The Resurrection Plot, 2015, Performa 15 Commission. Credits: Choreography: Pauline Curnier Jardin in collaboration with the performers Simon Fravéga d’Amore, Hélène Iratchet, Mikey Mahar, and Viviana Moin / Costumes and set design: Rachel Garcia / Assistants: Marjorie Potiron and Julia Stadelman / Music: Claire Vailler, Mocke Depret, Vessel / Production: Lafayette Anticipations, Performa Biennal NYC / Duration: 65 minutes / Languages: English, Italian, French.

Terry Eagleton, Walter Benjamin: Or Towards a Revolutionary Criticism, Verso 2009.

It is thanks to Judith Perron, her dance instructor at l’Ecole nationale supérieure d’arts de Paris-Cergy, that the artist has studied dance history and practice since 2001. Perron introduced her to the contemporary dance scene and to the feminist choreographers Latifa Laâbissi, Loïc Touzé, Catherine Contour, Jennifer Lacey, Antonia Livingstone and Antonia Baehr. This encounter also brought the artist into contact with Mickäel Phelippeau and le Club des 5, Bettina Atala and Grand Magasin, leading her to initiate a collaborative practice with Maeva Cunci, Aude Lachaise, Virginie Thomas, and the female-dada cabaret called Les Vraoums. The scenographer and choreographer Rachel Garcia remains a current collaborator in Curnier Jardin’s performative works.

Fredric Jameson, The Aesthetics of Singularity, New Left Review 92, March–April 2015.