Benoît Maire and Caterina Riva, Rome, February 2022. Organised in partnership with Villa Médicis - Académie de France à Rome.

When an unexpected invitation to write a text on French artist Benoît Maire landed in my inbox, I realised it had been more than ten years since I last engaged with his work. Back then, I was living in London and running a curatorial project space called FormContent while Maire was often visiting the city for various exhibitions.

As part of the research towards the writing commission, I was invited to spend a few days in Rome at Villa Medici, the French Academy situated at the top of Trinità dei Monti. Benoît Maire1 is currently one of the 2021-2022 Visual Arts Fellows. He occupies a studio apartment on the grounds of the luscious gardens populated by pine trees, sculptures and real-life, shitting peacocks.

From a curator’s point of view, getting reacquainted after more than a decade with an artist’s body of work provides a tabula rasa, a new beginning. The artist in question, as well as I, are some years older, yet Benoît looks pretty much as I remembered him, his glasses still a recognisable feature on his nose. I spot his figure from a distance as he walks to meet me by the military tank that patrols the entrance of the Foreign Academy. During lunch, we try to fill in the blanks of all those years of our lives that went by. I learn that he is married to Marie Corbin and that they have two children. I like how he tells me quite matter-of-factly: the year of a grant awarded to him followed by the year of the birth of a child.

My recalling of past encounters with Maire’s artworks reference philosophical queries – in language as well as structure – a difficult feature to interpret for someone not fluent in philosophy, a subject the artist has been studying at length.

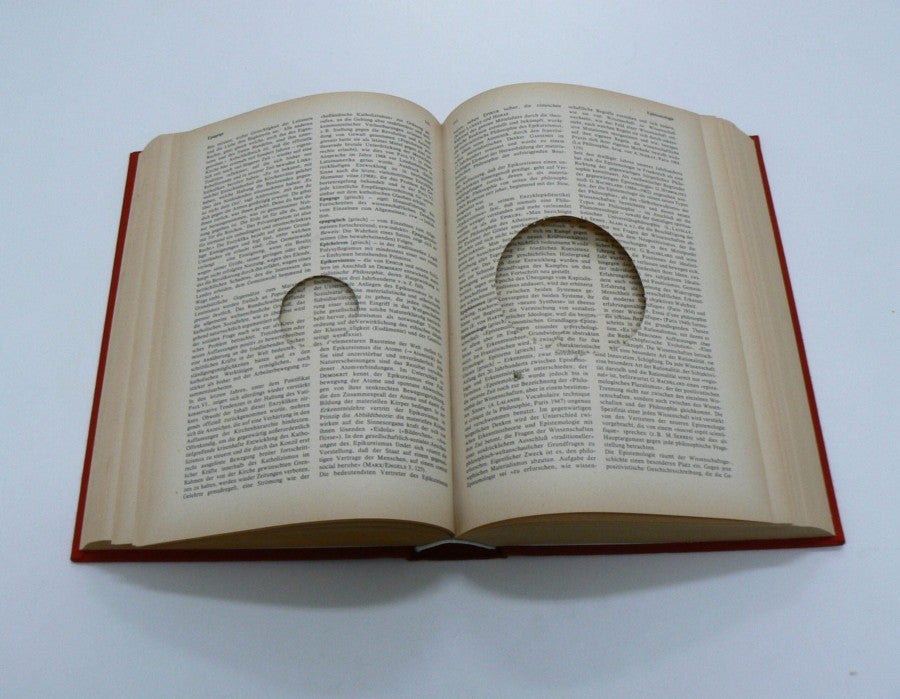

Holes in Philosophy #1 for instance, a work he made in 2008, which consists in cutting a round hole in the pages of an open Encyclopedia of Philosophy, makes visible to the viewer the literal gap existing between the idea, the meaning and the knowledge on which Maire props his work. A work from 2010 titled Le nez is made of a bronze head with an extremely long nose, that reads like a reference to either Pinocchio or Giacometti, perched on a wooden tripod. This hybrid creature, half human, half tool, becomes the measure, the paradigm of an invisible study: an askew compass pointing to the realm of ideas or hinting at another artwork with which it has a silent dialogue. These older pieces – perhaps no longer fully representative of Maire’s current artistic thinking and output – can however help figure out some of his initial strategies and unpack a few of the artist’s concerns when it comes to assembling his artworks. Maire builds spatial and physical summaries of philosophical axioms by compressing several layers of meaning in the distilled forms of his aesthetics. By reducing to a minimum the terms of materials and forms, the artist adheres to a consistent syntax he has established and fed throughout the years. His signature conceptual penchant is then embodied in the finished piece and echoes of philosophical queries resurface at each addition to his repertoire. I like to think of Benoît Maire as caught in a protracted chess game with himself and whoever decides to decipher the artworks facing them.

Logical Paintings

Prior to reconnecting with Benoît in Rome, I decided not to rely too much on what I could find on- and offline about the books, exhibitions and projects he had been busy with in the years we lost touch. I wanted to instead adopt an empirical evidence approach: wait to witness some of the works in the flesh and hear from the mouth of their author.

Entering his studio apartment at Villa Medici, first in November 2021 and then in February 2022, has offered me a privileged look into a series of new works, mostly paintings, which Maire is working on and living with, as they are hung in the rooms he inhabits when he is not in Bordeaux with his family.

Maire has found a way to marry his theoretical concerns to an aesthetically cogent painterly praxis...

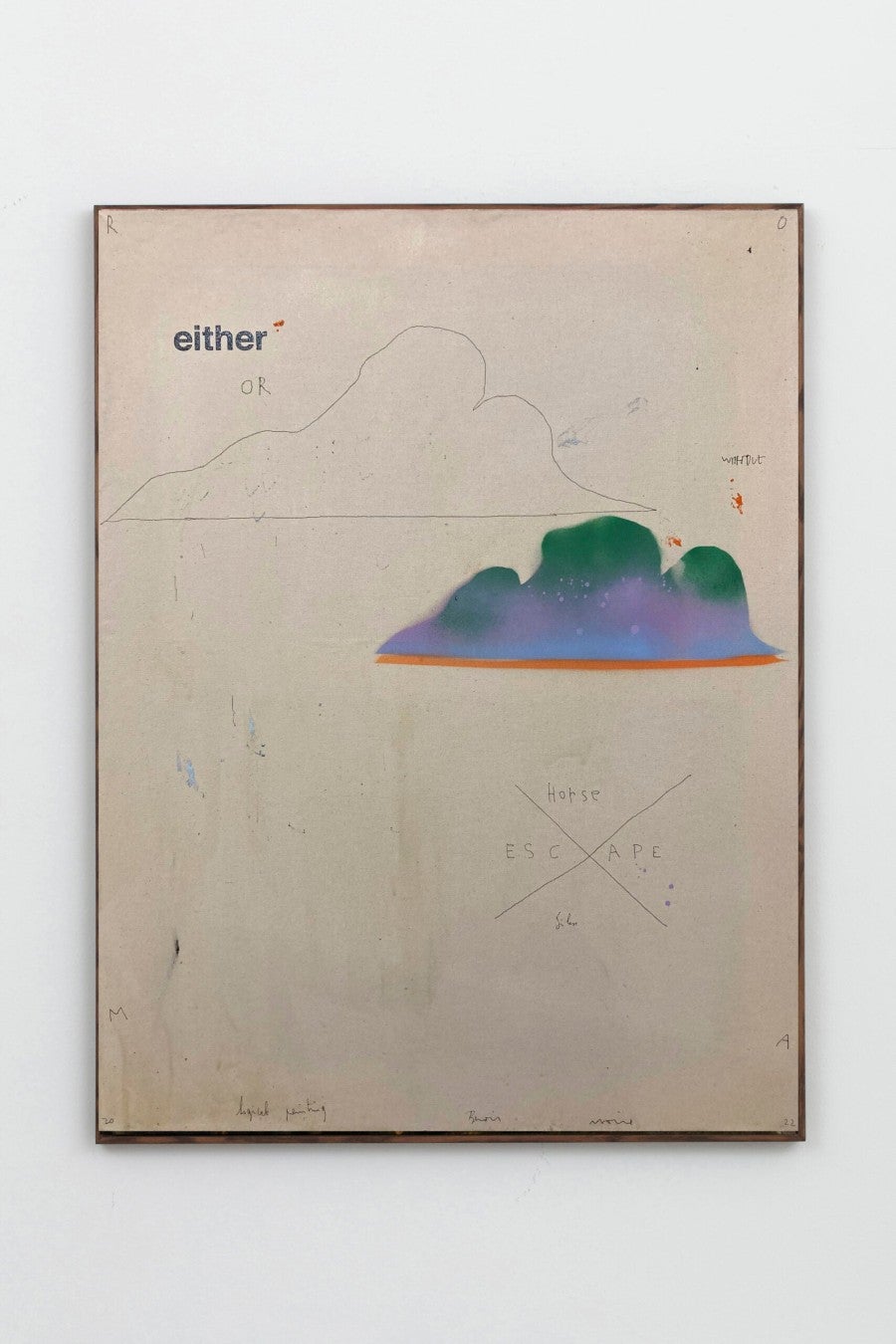

Maire refers to this new body of work being developed in Rome as Logical Paintings (Peintures logiques), which can be considered as his latest enterprise – in fact, he took up painting around 2012 without formal training as I learnt when we came together at Villa Medici. In response to my queries about his Cloud Paintings – the artist’s take on post-painterly practice combined with his omnivorous tendency of digesting lessons from, among others, Impressionism, Conceptual Art, Abstract Expressionism, Renaissance painting – I am given a copy of the catalogue from his 2018 solo show, Thebes at CAPC, the Contemporary Art Museum in Bordeaux. The act of calling them Cloud Paintings introduces head-on Maire’s thinking structure on which rests the act of painting a cloud on a canvas. Dutch Professor Mieke Bal writes in the same catalogue that she has come to the following conclusion: “what Maire is telling us, as a visual philosopher of visuality, can be summed up as the insight that painting is itself a cloud.”2 Maire has found a way to marry his theoretical concerns to an aesthetically cogent painterly praxis: the ideas, rather than contained by the materials, are funnelled through them, very much like in the data-gathering banks of our computers that we call the ‘cloud’. The result is a technological space of computation as well as of contemplation, an ever-evolving algorithm which we don’t see the workings of but which we know is constantly gathering and releasing information. The artist’s studio is where physical gestures are performed on the canvas and also the space in which abstract compositional rules are applied: tested out through pictures taken with a smartphone and visualised through a computer screen, anticipating further developments on the surface while layers of oil dry close by. Painting 3.0 cannot exist outside our interconnected digital lives, so visiting Ettore Spalletti’s installation at Galleria Nazionale in Rome and finding interesting contemporary paintings and painters on Instagram both constitute worthwhile research for Maire.

During my first visit to Rome, in the two consecutive days I spend in the studio, the paintings are at different stages of development and I conclude that the artist is a much faster painter than I had anticipated and that he works mostly at night. It is remarkable to consider that he trained himself to paint after having adopted in his previous productions mostly words, sculptures, films and assemblages. The stakes are high: on the one hand, painting exists in contemporary discourse as a more accessible artistic medium which also translates into a more commercially viable medium; on the other, to master his own ‘style’ the artist needs to process so much history (past and present), theory and technical decisions. Clouds provide a vast horizon of interpretation, beyond chronological time, allowing Maire to construct an intellectual proposition while working on its representation. This process, both material and mental, allows for layers, changes, mistakes and additions, like the editorial work behind writing this essay, in which some paragraphs will be cut while others resurface in different shapes.

Cracking the enigma

I am going to analyse some of the features I have observed in Maire’s paintings, like the pieces of an enigma set out by the artist for me to solve.

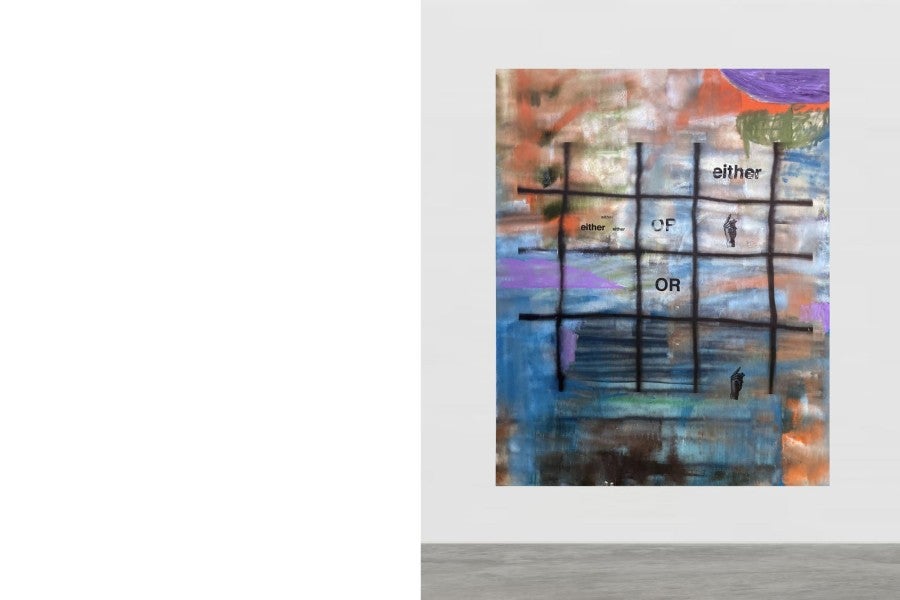

Throughout Maire’s oeuvre, iconography plays an important role. First in his use of hands, typically taken from Flemish masters or the Italian Trecento and Quattrocento painters such as Gentile da Fabriano (c. 1370-1427) and depicting either male or female palms. Western art history provides an endless archive of gestures for Maire to pick from, yet the repetition of the same each time creates new semantic possibilities. Floating hands are transferred by Maire on the canvas through pre-manufactured screens, thus allowing them to point in different directions as if they were slating arrows in a non-Cartesian coordinate system. Western interpretations of Medieval and Modern Art figurations consider hands as a conduit between the spiritual and the bodily world. For Maire, I believe they are pointers in the complex structure of perception and composition that his paintings map. Secondly, his repeated use of EITHER/OR3, screenprinted in black ink capital letters on the canvas, infers a decision between two elements that are not clearly presented within the context of an abstract painting. His EITHER/OR logic could pertain to the visual sphere, the philosophical one or else the pair might trigger a reflecting mirror between the artist’s gesture and the act of viewing.

In analysing Maire’s approach, I am constantly caught in a bind whether to describe the conceptual and physical apparatus that generates the artwork, mimicking the artist’s explanation and thus becoming a spokesperson for his sophisticated logic, or to deconstruct instead his intention and just follow my own train of thoughts. I choose to settle for a conversation between the two options.

What I see in the studio is a continuation of works that the artist was making before Rome. However, the proximity to certain stimuli specific to the Eternal City could be singled out in their development: like a special kind of sunlight which modifies his colour palette, or the visits to Rome’s museums and churches, or a fragment of paint from Giotto encountered in an antique dealer shop. Likewise, the lamps designed by Balthus (1908-2001) for Villa Medici, which can be found in almost every room of the French Academy, might have influenced the metal lamps in the shape of castles (lampe Médicis) that I see in his living room and that will follow him in France at the end of the year.

In Maire’s picturesque temporary residence, grids return as an intermittent feature, spray painted by hand on the top layer of his paintings. As a painting device, the grid may have emerged in Maire’s works as a result of Covid-instigated lockdowns, when looking out of a window or at our screens were the only interfaces we measured up against and which framed our vision and horizon of perception. A grid establishes a viewing device – a window again – that the viewer tries to look into while the painting itself looks out of. The grid can also reference architectural details within an exhibition space. For example, Maire’s painting for La Nuit Blanche festival at the Villa in 2021 was installed – according to the artist’s consistent display rules – at the edge of a wall close to a window covered by an actual metal grid. Hence, drawing a grid proposes at the same time a mimesis of the real and an allegory of a dematerialised elsewhere.

By a table where a sewing machine is installed, I find a rack with t-shirts in various colours that Maire has been drawing on, bleaching and repeatedly printing a kneeling character, recognisable from art-historical sources for the nose and bowl-cut hair as the nobleman, warlord and patron of the arts Sigismondo Malatesta (1417–1468). In European Medieval and Modern Art History, a kneeling figure, portrayed in profile and with hands pressed together normally facing the holy scene at the heart of the representation, usually personifies the donor, that is, the person who commissioned the painting. Rather than with saints or religious epiphanies, Maire’s t-shirts combine the figure of Malatesta with the word SEX, introducing carnal desire into the exchange between the artist and the buyer who will eventually wear the garment, stressing the idea of a capitalist transferral of status that has little to do with Christian repentance.

Fashion design is certainly a production field to which Maire pays attention. In one of our chats, we recall Ghanian-American creative director Virgil Abloh’s (1980-2021) premature passing and discuss his ability to work in a large range of collaborations, drawing from art, design, architecture and music, as well as his ability to turn streetwear into luxury clothing, in a continuous sampling and switching of codes.

Distribution and collaboration

The work was meant as an escape, it was worth a kingdom,

suddenly it takes on the weight of an obligation,

the safest way to earn a living.

– Benoît Maire4

Benoît openly discusses the way that his creations infiltrate the world and the economies applied to different modes of production and distribution...

During his year in Rome, Benoît doesn’t seem distracted by Villa Medici’s suspended time. He has focused on making work for all strands of his production cycles, branching out to new collaborators and collaborations. I appreciate how Benoît openly discusses the way that his creations infiltrate the world and the economies applied to different modes of production and distribution, through exhibitions, gallery shows, sales and editions. In our conversations, he speaks frankly about the issue of financial sustainability and how this is inextricably linked to being an artist but isn’t always acknowledged as such.

Around these considerations, I become aware of Ker-Xavier5, the design brand he has set up with his wife and collaborator Marie Corbin. Together, they produce and sell furniture items such as tables, chairs, lamps and stools, both for domestic interiors as well as exhibition design. I’m told that the dozen wooden stools which occupy a sizeable portion of his living quarters at the Villa when I visit for the second time have been made with a Roman carpenter for Ker-Xavier.

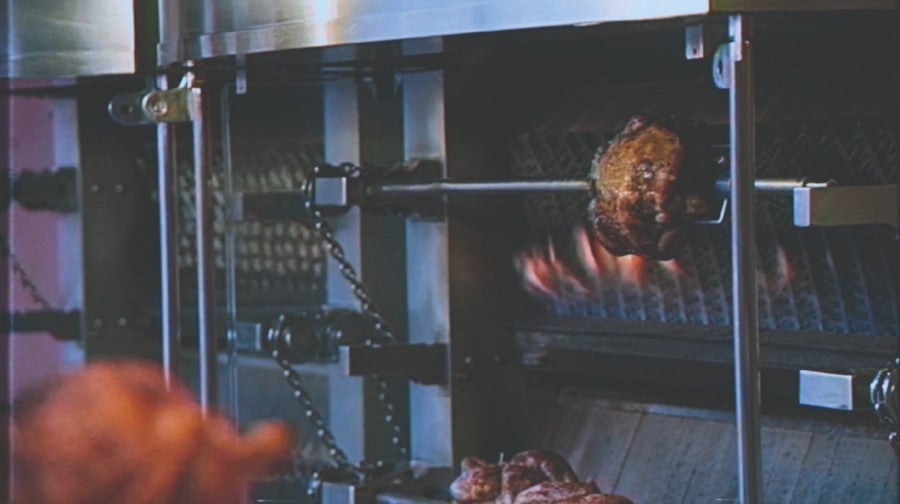

There are two other mediums with which Maire has been engaging throughout the years: making films and curating exhibitions, which, to me, reveal the continuation of his artistic work and sensitivity in other formats. In 2018, Maire wrote and directed a short film titled Le Mot Origine in which the camera follows the deeds of everyman Pierre Georges. The protagonist’s day starts with a soft-boiled egg for breakfast while he listens to American political scientist Francis Fukuyama discussing the end of history on French radio. The main character reaches his office (situated in a Brutalist building in Bordeaux) and after some meetings, he goes to a rotisserie, buys a chicken for lunch and chews on it alone in a park. Another day, he eats hard-boiled eggs, breaking and peeling one for the camera. The film channels Maire’s deadpan humour, paired with a semi-ironic, semi-melancholic tone. The protagonist dresses a bit like the artist, while the plot repurposes in a modern environment the ancient Artistotelian paradox of “the chicken and the egg”: which one comes first? Film could lend itself as a good mirror to Maire’s philosophical thinking but when I ask his feelings about it, he confesses that he doesn’t have what it takes for big filmic productions, embodying the magnetic director and how needing to boss many people around is “not in his nature”.

Exhibitions, both his own as artist and the ones he organises as curator with other artists, are another outlet in which aspects of the logic he follows in the making of his artworks plays out in an expanded arena. For instance, he carefully considers how artworks need to be put in relation to each other on a wall, following precise analytical considerations, constructing a spatial layout that challenges the usual centralised perspective in favour of other symmetries. In addition to these, he has introduced the idea of waste (“les déchets”) in the context of the exhibition display of his own solo shows. LETRE, Maire’s 2014 exhibition at La Verrière in Brussels, was the first manifestation and presentation to include, alongside the outcomes of his artistic process, the material and immaterial leftovers that led to the artwork but are not part of it. The waste comprises arranged objects, usually placed on the floor, creating a harmonious constellation that challenges a hierarchical value assignment. They present strings of ideas in a very neat layout, elevating it to the status of artwork.

It’s like being caught in a Hitchcockian crime scene.

The exhibition apparatus offers Maire the chance to put thoughts, objects, colleagues and collaborators in relation to each other while interweaving boundaries and perspectives from various disciplines and fields of knowledge.

In 2019, Maire was invited to guest-curate a group exhibition at Le Plateau in Paris with a “substantial budget” (the artist tells me without prompt). Foncteur d’oubli was the resulting project, gathering works in relation to functionality by an intergenerational group of artists, designers and architects. The display created by Ker-Xavier (many hats are worn by the same man) for the exhibition favoured a white palette of furniture and intense round lights to draw attention to the selected pieces and their juxtaposition. Maire inserted in the exhibition, among loans from other institutions, works of colleagues and friends, pieces from his own collection of ceramics and objects. Yet another hat for Benoît Maire.

A week before our second gathering in Rome, Benoît sends me via email a two-minute video clip recorded in his studio for a public presentation, scheduled at Villa Medici. In the clip, the camera zooms in on stuffed birds that I haven’t seen before and captures new paintings and sculptures. A music score, composed and performed by Maire’s friend (Hèctor Parra, also a resident of the Villa this year) on the grand piano in his living room, accompanies the visual discovery. It’s like being caught in a Hitchcockian crime scene. A round, white canvas impressed with the word FILOSOFIA and a wooden ball with the word ART come to the foreground; moments later I realise that they are being juggled horizontally by a young man who, as the end credits reveal, is the curator. To recap: the ART object falls from the philosophy tray, thus breaking the veil of the spectators’ disbelief. The viewer then questions whether they witnessed the curator’s unwarranted slippage or the artist’s perturbation plan, and if the two actions are consequential. This is a good example of Maire’s ability to construct a visual-logical proposition, directing the viewer’s gaze while distilling the visual information to a selection of signs, containing in turn layers of signifiers – which of course generates more questions.

On 10 February 2022, there is a public talk in the cinema room of the Villa, held to present the behind-the-scenes of a text that is still being written and to introduce the artist (Benoît Maire) and the writer (myself) engaged in this experiment. The next day, I meet Benoît to shoot a short scene of a film he is making. He invited me to be part of it when I first came to Villa Medici. As a stage set, we are using the room of the previous night’s presentation as we left it: Maire requested that used glasses and water bottles were not to be removed. I sit again at the conference table, in the same spot I sat the night before, an image of a Maire artwork from 2010 projected behind me. Maire sent me the image beforehand and asked me to prepare a little speech in Italian from the point of view of an art historian, which happens to be my university qualification. The sculpture is titled La conference dechirée (The Torn Conference) and consists of a table with a transparent glass top, resting on three legs, two of which are made with different kinds of tree branches and the third a white sawhorse, which looks like an empty frame. I talk about Leonardo Da Vinci’s Last Supper in Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milano, Modernism and Les trois écologies, the 1989 essay by Felix Guattari which was the departure point for the exhibition I had just opened at MACTE Museo di Arte Contemporanea di Termoli, the museum I am directing on the Adriatic Coast of Italy. I am not sure whether this short recording will make the cut or exist only as waste material. I am still wondering if this was Benoît’s strategy all along: inserting me in one of his works, like a pawn in a chess game that we are continuing to play.

The author would like to establish some rules applied to this text when discussing Benoît Maire: employing his first name when profiling the man and surname when addressing the artist.

Mieke Bal, Ungraspable: Benoît Maire’s Cloud Paintings, in the 2018 CAPC catalogue of the exhibition by Benoît Maire, p. 56.

“used to refer to a situation in which there is a choice between two different plans of action, but both together are not possible” Either-or definition by the Cambridge English Dictionary

Poem composed by Benoît Maire on his smartphone 30 August 2017 and printed in Benoît Maire, Un cheval, des silex, 2020 (Paris: Editions Macula) p.100.

Named after Ker-Xavier Roussel (1867-1944), an artist associated with the Post-Impressionist painters’ group Les Nabis.