Carrying histories: Earth and fire, metaphors and metamorphosis, in the ceramic practice of Thu-Van Tran

Encountering Coolamon, a preface

In our earliest online exchanges, leading up to our first in-person meeting in Australia, artist Thu-Van Tran tells me how she has been inspired by the ‘Coolamon’ (Wiradjuri/Wiradyuri: gulaman), a precious Indigenous object1:

In Aboriginal symbology, this vessel is traditionally used to carry food or to cradle children. It’s a beautiful example of how an everyday object, seemingly modest, holds deep significance — honoring care, family and community life.2

It’s heartening to hear that Tran, a leading French-Vietnamese contemporary artist who was born in Ho Chi Minh City and has lived and worked in Paris since a young age, is learning about Australia’s Indigenous histories, cultures and creativity during her long-term international studio residency in Boorloo/Perth, Western Australia. She has been hosted by the Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts (PICA), as part of its International Studio Exchange Program, during the Indigenous Noongar seasons of the first half of 2025, starting her residency in the hottest season of Bunuru (February–March), with its flowering gum trees and reddening seed cones, through to cooler, damper and breezier weather in Djeran (April–May), with its red florals and red rusted she-oak trees, and ending at the very beginnings of the coldest and wettest season of Makuru (June–July) marked by its blue and purple flowers and the influx of birds preparing to nest and breed for the remainder of the season.

Over the course of her residency and these changing seasons, Tran had been experimenting with ceramics in particular—more precisely, ceramic vessels or receptacles that have the potential to receive, to hold, to carry, to cradle, invoking her latest knowledge of the Coolamon. I am reminded of the many Indigenous cultures of the world in which the ‘carrier’, as a container and technology for gathering and sharing, continues to hold so much significance. It is something which author Ursula K. Le Guin helped to popularise in the late 1980s with her celebrated essay ‘The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction’3 and which later, feminist theorist Donna Haraway linked with Indigenous activist and creative cultures of Columbia in an introduction she wrote to accompany the republication of Le Guin’s essay in 1996.4 For Le Guin, the ‘carrier bag’ symbolised a different set of relations among humanity, one centred on community, gathering and sharing, rather than technologies valorising the heroics and violence of war, conquest and domination. Quoting from feminist Elizabeth Fisher, Le Guin points out in her essay that,

Many theorizers feel that the earliest cultural inventions must have been a container to hold gathered products and some kind of sling or net carrier.

Le Guin goes on to underline the utmost significance of the carrier when she asks,

…what about tomorrow morning when you wake up and it’s cold and raining and wouldn’t it be good to have just a few handfuls of oats to chew on and give little Oom to make her shut up, but how do you get more than one stomachful and one handful home? So you get up and go to the damned soggy oat patch in the rain, and wouldn’t it be a good thing if you had something to put Baby Oo Oo in so that you could pick the oats with both hands? A leaf a gourd a shell a net a bag a sling a sack a bottle a pot a box a container. A holder. A recipient.

Before—once you think about it, surely long before—the weapon, a late, luxurious, superfluous tool; long before the useful knife and ax; right along with the indispensable whacker, grinder, and digger—for what’s the use of digging up a lot of potatoes if you have nothing to lug ones you can’t eat home in—with or before the tool that forces energy outward, we made the tool that brings energy home.5

Haraway’s later framing of Le Guin’s text repositions the vital significance of the carrier bag within contemporary communities in Columbia who are ‘carrying’ out urgent environmental and racial justice work at this critical time of the Anthropocene—a reminder of the integral role of the carrier as an essential form in enabling acts of care and activism. Indeed, the carrier vessel has long been valued, across a variety of cultures of the Majority World, that is, outside the West, in practices of gathering, carrying and sharing, especially in Indigenous and matriarchal societies.

(...) Tran sought to underline the ceramic vessel as an important carrier – of life, and of sacred or other valued objects.

Similarly, for her work at PICA, taking inspiration from the Coolamon, Tran sought to underline the ceramic vessel as an important carrier—of life, and of sacred or other valued objects. Moreover, she highlights how ceramics, in their materiality, are also carriers of a specific history of a place and time, embodied by the particular soils or clay and natural pigments they are produced from, and imbued with the techniques and conditions of their making. Significantly, symbols or metaphors also uniquely manifest in ceramics through both the deliberate and unpredictable transformations of earth and fire in ceramic practice. What physical and symbolic stories of a place and people can such carriers or containers of history tell us? As Tran explains, “using clay, using land, it's also a way to refer to humanity for me… it carries its history but also its physical composition, its energy and its history.” It recalls an interview I came across while researching Tran’s work, where the interviewer recalls Tran’s powerful statement: “Memory is our medium and we live in matter.”6 In this, not only does Tran register the constructedness of memory and memory-making as an ongoing process, but also that our histories—be they economic, political, social, or ecological—can be readily traced through matter, to materiality, to objects.

Tran also tells me about her conversations with Indigenous Nyoongar artist Sharyn Egan as part of her interest to understand the local knowledge ecologies and natural materials that inform Indigenous creative practices in Western Australia. With Egan, Tran came to understand the particular qualities of the regional landscapes of Boorloo and its neighbouring Indigenous Countries. She became especially interested in the local soils, the use of natural pigments derived from the local landscape, and how the earth is transformed within the Australian landscape by the powerful elemental force of fire—respected by Indigenous people as both a destructive and regenerative, life-giving force given that, after catastrophic fire events, landscapes experience renewal, new growth, and changed conditions. Australians Bill Gammage and Bruce Pascoe have written about how Indigenous people have long honoured and wisely harnessed this transformative power of fire in their traditional fire burning practices, systematically and scientifically using ‘fire-stick farming’ or ‘cultural burning’ techniques to strategically manage their lands and fires.7 Recent environmental practices in Australia are finally acknowledging the value of these Indigenous ways of caring for land after centuries of damaging consequences on the Australian landscape stemming from the imposition of ill-fitting, colonial approaches.

Of Earth and Fire

The Indigenous reverence for the dual quality of fire is also of deep interest to Tran in her practice. She thinks about it in terms of the Vietnamese Buddhist culture she grew up in, “where we trust consequences of cycles” she says, the natural energy cycle of new life which follows catastrophic fire events. Birth, life, and death, she explains, are always in communion in Buddhist thinking. It was in this sense that Tran connected the cycles of nature and culture to the elemental forms of earth and fire to create her new ceramic works during her residency at PICA. Alongside this interest in nature’s cycles however, is also her interest in the impacts of colonisation and industrialisation on the Australian landscape and Indigenous Country—indeed, these intersecting themes of nature, colonisation, and industrialisation repeat throughout Tran’s oeuvre as consistent lines of enquiry. In Boorloo, Tran is particularly conscious of the huge mining industry that dominates the Western Australian economy and sustains the national economy of Australia—that is, as anthropologist Anna Tsing observes, the capitalist-driven transformations of the environment (or ‘second nature’).8 Landscapes such as Kalgoorlie, which Tran visited during her residency, have been thoroughly changed by mining activities—previously primarily for prospecting gold, and now for the extraction of nickel, lithium, iron, and other rare earth elements. Invoking Tsing again, what might possibly survive in this landscape after the ruins of capitalism?

(...) these intersecting themes of nature, colonisation and industrialisation repeat throughout Tran’s oeuvre as consistent lines of enquiry.

I’m reminded of my first encounter with Tran’s artwork, just a few years before, as part of the compelling exhibition Reclaim the Earth, held at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris in 2022, aptly described as ‘a wake-up call’ and ‘rallying cry’ for humans to urgently reconsider our relationship with the planet and look beyond the ‘nature-culture‘ divide that has been established through Eurocentric paradigms. For that exhibition, with its interest in tracing different artists’ approaches to the different elements of earth, air, fire, and water, as well as plants and minerals, Tran presented her dramatic photographic installation De Vert à Orange – Espèces Exotiques Envahissantes (From Green To Orange – Invasive Exotic Species) (2022), a ‘botanical diorama’ awash not in verdant greens but with intense hues of enflamed orange. The eight-part scene imaged a landscape of flourishing plants taken from tropical environments as part of colonial expeditions, but which ironically, once introduced into the West for botanical pleasure and ornamentation, became highly toxic and invasive within the new, foreign ecosystem—as Tran describes it, “a lush wilderness vanishes and is in turn reborn amid fire and fury.”9

Tran’s interest in fire was taken up again for her residency in Australia, but it combined her fascination with the power of fire as elemental force, and its wondrous and destructive possibilities in nature, alongside its essential role in ceramic practices. She had originally intended to visit Australia some years before in the summer of 2019–2020, however a major bushfire hit the country that summer—colloquially known as ‘the Black Summer’—followed by the global COVID-19 pandemic, postponing her visit until now. She mentions how seeing images of the Australian bushfires from a distance in France left a deep impression on her, and she began contemplating how the metamorphoses that occur in nature due to fire can be connected with the use of fire in her ceramic processes, whereby fire ignites a process of metamorphosis in ceramic materials which are themselves the stuff of clay, soils, and pigments from the earth. She elaborates on her motivations as such:

I wanted to dedicate my research and residency to fire and earth. The 2019 bushfires affected me deeply and delayed my arrival in Australia, but that wasn’t my only motivation. I use fire in my practice as a process of revelation, a passage, a trial. After this trial by fire, metamorphoses appear. Fire allows matter to metamorphose, and thus a new existence is born. I wanted to embody fire, even symbolically. That’s why I thought of urns, of closed forms. But not forms to contain the ashes of departed loved ones, but to preserve a memory, a history of matter, earth, and fire. A form as a metaphor for this geological humanity.

Before I meet Tran, I visit the Art Gallery of Western Australia. At the ground floor exhibition of Indigenous art, by chance, I encounter several Coolamons. I am first struck by the beauty of a woven Coolamon cradling the figure of a baby, crafted from grasses—the artwork Baby (1999) by Joyce Winsley, of Wilman and Goreng ancestry. Traditionally, the Coolamon is a large and shallow dish-like vessel of roughly 30–70 centimetres with curved sides, mimicking the shape of a canoe, and was principally used by Indigenous women to carry water.10 Over time, the term has been adopted to describe other types of carrier vessels found in different Indigenous communities across Australia, to carry water as well as to hold food and herbs, to transport fire embers from one place to another to begin new fires, and to cradle babies, among other purposes. The different Coolamon and other Indigenous carrier types I encounter in the gallery each hold stories, memories and histories in them of Indigenous communities and Country. Moreover, their inclusion in the art gallery acknowledges the creativity and artistry that each embodies.

I carry these images and stories embodied by Coolamons with me in preparation for my first meeting with Tran. We sit at a table outside in the late morning sun of Makuru to find out more about each other—myself, an art historian of the contemporary art of Asia, especially Southeast Asia and its artist diasporas—and for me to learn more about Tran’s intense period of honing her ceramic ‘carrier-making’ skills in Boorloo.

Sculpting histories, from the diaspora

Tran is a contemporary, multidisciplinary artist, whose practice consistently engages with the possibilities of sculptural forms and installations, often via an expanded sense of ‘sculpture’ that is in dialogue with painting, photography, film, architectural and monumental forms, as well as natural environments. As with other artists of the Vietnamese diaspora, the artist’s practice has also connected her Vietnamese ancestries with intersecting colonial histories, especially that of French Indochina. Her works reflect her experiences navigating different cultures, languages, and national identities between Vietnam, where she was born in 1979 following the Vietnam War, and France, where she and her family fled to in 1981 when Tran was just two years of age.

Tran cites literature, architecture, and history as important reference points for her sculptural practice to date. Prior to her residency work at PICA, among other notable ‘sculptural’ works that Tran has produced are her installations: Red Rubber (2017) for the 57th Venice Biennale, with its striking wax casts of rubber tree-trunks, exploring the consequences of introduced rubber plantations in Vietnam; Peau Blanche (White Skin) (2017), with its haunting gathering of white plaster casts presented in blue cases—reminiscent of dismembered body parts—each cast moulded directly from parts of statues erected in Paris in the 1920s to commemorate the glory of French colonial expansion; Barque du Palacio (Palacio’s Boat) (2007), an archetype of a boat, made of wood, that appears trapped in the physical confines of its ‘retrofuturist’ apartment complex; 82 Tortues Me Disent (82 Turtles Tell Me) (2019) consisting of 82 wax tortoises supporting stelae on their shells, and the related film 24 heures à Hanoï (24 Hours in Hanoi) (2019), based on the artist’s day-long trip in the northern Vietnamese city, both paying tribute to the fifteenth-century stone turtle stelae at the Hanoi Temple of Literature, a monument honouring Vietnamese scholars; and Roman sans Titre (Novel without a Title) (2018) evoking a forest floor in the aftermath of fire with its scattered gathering of hundreds of burnt ceramic leaves, each shaped by an individual rubber-tree leaf from a plantation in South Vietnam—a work Tran created with artisans from the famed Vietnamese ceramics village of Bát Tràng.

Continuing her interest in sculptural installation, in Boorloo, Tran’s final installation of over twenty ceramic works presented at the end of her residency period at PICA offers a sprawling array of carriers in myriad shapes and hues, recalling the essential qualities and traits of one of the primary art forms of ceramics—sculptural pottery. Her installation is a response to the environment of Western Australia and a homage to this humble, vernacular pottery form, so integral to humanity, the carrier vessel. As Tran explains,

When we hear ceramic, we also immediately think of pottery, because we use clay to build functional objects for our daily lives, like recipients or plates… I really want to draw attention to this aspect of ceramics and to useful objects. For me, it’s about Mingei, the Japanese philosophy that recognises the dignity of craftsmanship and the elegance of modesty in everyday objects—bowls, jars, baskets, textiles—imbued with a spirit of community and grace.

Alongside this emphasis on the utility of the ceramic object, the sophistication of Tran’s installation underlines the historically overlooked beauty and creativity of simple, handmade functional art and crafts created by ‘anonymous’ crafts people, especially those often found in colonial museum collections. Her work seeks to “honour the beauty behind such daily life objects for what they keep in their humble existence and also their humble way of appearance,” recognising that in the past their makers lived simple, humble lives but nevertheless crafted these handmade objects with utmost care and attention for use by all people in their everyday life. This respect for craft and craftmakers is also shaped by Tran’s time working with the Compagnons du Devoir in the early 2000s, a companionship of craftspeople in France dating from the Middle Ages. Similarly, Tran notes, in his development of ‘Afro-Mingei’, a hybrid of Japanese and Black cultures, Black American artist Theaster Gates celebrates the creativity and even political resistance to be found in everyday craft practices, and honours the historically unidentified people who crafted such objects for a living.

Tran explains to me how Indigenous iconographies left a deep impression on her because of their capacity to express profound meaning via a sparing yet highly evocative visual vocabulary.

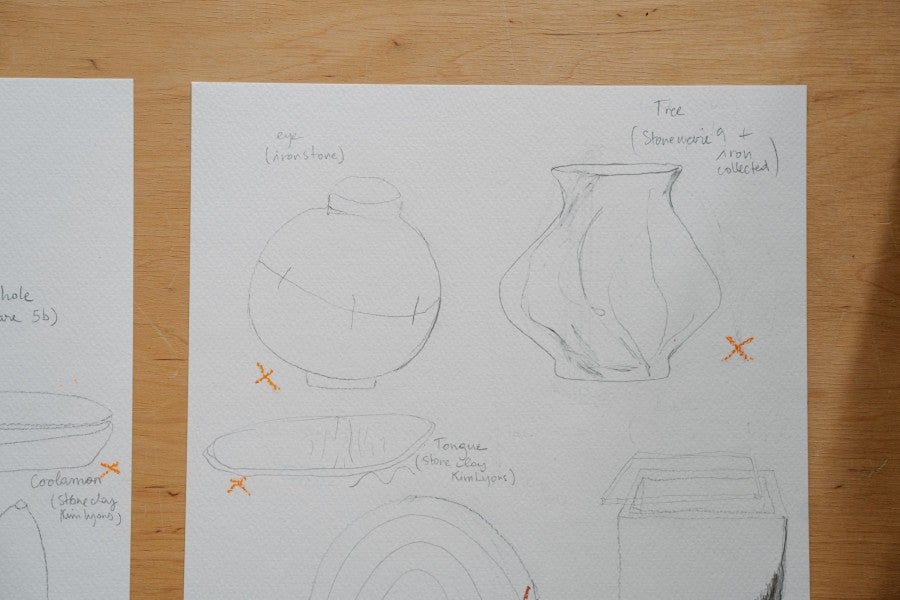

In preparation for her ceramic carriers, Tran sketched beautiful lead-pencil drawings that evoke different concepts and serve as a reference for the final ceramic carriers. They are each an individual response to an initial set of drawings “based on a word or an allegory of nature and life”—Star, Planet, Egg, Breath, Half-Breath, Person, Little Person, Moon Noon, Mouth-Song, Smoke-Fire, Spirit, Rainbow, Path, Tree, Human Tracks, Shield, Eye, Waterhole, Rain, Reversed Mountain, Song, and of course, Coolamon. They are reminiscent of the important visual symbols of Indigenous Australian iconography, as a way to communicate messages and stories. Tran explains to me how Indigenous iconographies left a deep impression on her because of their capacity to express profound meaning via a sparing yet highly evocative visual vocabulary. I ask Tran some more about where the words came from. She explains that she was interested in the idea of lyrics that could invoke one’s first encounters with nature here in Australia, wondering what those lyrics could be:

I started gathering words. Together, these words form a song. The lyrics talk about us with and in nature, in a broad sense; it’s subjective and very poetic. The words can refer to the cosmos, the stars, a rainbow, a planet, they can also be linked to the way we come into the world (...) In my opinion, taking an interest in symbols and allegories is a way of living through metaphors. I think we need to explore our allegories, metaphors, and imaginations more, rather than wanting to be intentional, unambiguous and literal.

As we study the reference drawings we can note the different words attached to each ceramic shape, the particular kinds of clay or pigment used, and the types of pottery technique that characterise them: for instance, the browned Egg, in gold raku clay, is conical in shape with a wrinkled skin; Planet, in gold raku with a sandy finish, is bulbous with a belly-like opening at its top; the stoneware piece Breath is cavernous with a narrow mouth opening, as if blowing air from its top; Star, made of iron stone, is dark and bulbous with a single ring of spherical indentations around its middle; Rainbow recalls a turtle shell with ‘rainbow’ arches across its back; Eye, consisting of two ironstone bowls balanced atop of each other, stands out for its cobalt blue and pupil-like protrusion; and the integral Coolamon pays tribute to the traditionally elongated dish-like carrier, but with a bright yellow cover. Meanwhile, Tongue is a distinctive curled carrier of sorts with its relatively flatter, albeit undulating shape—it is a tribute to the power of language itself, symbolised by the tongue, to metaphorically hold and carry culture, people, places, and histories across time and space.

As a collection, Thu-Van Tran’s carriers are suggestive of a typology of carrier shapes, and a glossary of symbols or metaphors. Some glisten in the light, with their glazed surfaces commanding our initial attention, while others bear more muted, earthen colours. Some are more low-lying, flattened, and bulbous, others take on elongated, triangular, and pointed or conical forms. Some bear covers or lids, others are gaping and cavernous, as if mouths wide open. Some are whole and complete, in and of themselves, while others seem to remind us that they are necessarily parts of a whole.

A maker, known

On my last day in Boorloo, I visit the Art Gallery of Western Australia again. This time, inspired by Tran’s ceramic works, I make my way to the gallery’s sculpture collection. There is an assortment of both historical and contemporary sculptures. On this occasion, I am drawn to the more modern and contemporary works interspersed throughout the more classical pieces, mindful of how Tran also continues the long-standing tradition of ceramics as a contemporary artist.

My final visit is to the adjacent Western Australian Museum Boola Bardip, with its scientific and ethno-cultural collections. With little time remaining before I leave Boorloo, I ask the docent to help me: “Do you know if the Museum has any Coolamon objects on display?” I’m astounded at the breadth and precision of the docent’s knowledge. She takes a map of the museum and quickly circles the locations of all of the Coolamons she recalls on display. I take the map with me to locate over a dozen Coolamon and other carrier objects. In too many historical instances though, the maker is stated as unknown. But, of course, someone knew these makers, at some time. The maker was actually once known, not unknown.11

In the case of Tran’s carriers, we are invited to recall the multiple ways these traditionally humble craft vessels have embodied deep meaning and profound beauty for many throughout history, a testament to their makers and their contexts of making. As symbolic expressions, they represent a language for relating with nature, reflecting Tran’s experiences of intercultural sharing and learning in Australia; indeed, as a foreigner to Australia, finding a relatable language with and through nature was key to Tran establishing cultural connection. Thus, Tran’s carriers remind us not only of the creativity held within them, but also their integral relationship to the people, cultures, environments, and materialities which shape them, their valued role and function in sustaining everyday life and nurturing communities, and their continuing symbolic significance as carriers of stories and histories.

Coolamon is an Anglicised version of the Indigenous word ‘gulaman’, meaning a vessel or dish for carrying water. Its name derives from the language and Country of the Wiradjuri/Wiradyuri people located in what is now otherwise known as New South Wales on Australia’s eastern coast, where Coolamon (water) holes can be found in the landscape. See Wiradjuri Study Centre, WCC Language Program: Wiradjuri Dictionary, https://wiradjuri.wcclp.com.au/ (based on Stan Grant and John Rudder, A New Wiradjuri Dictionary, O’Connor, Australian Capital Territory: Restoration House, 2010); and Queensland Art Gallery / Gallery of Modern Art, ‘Coolamons’, https://collection.qagoma.qld.gov.au/page/coolamons.

All quotes by Thu-Van Tran are excerpted from conversations with the author, between April and June 2025.

Ursula K. Le Guin, ‘The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction’, in Dancing at the Edge of the World: Thoughts on Words, Women, Places (New York: Grove Press, 1989).

Donna Haraway, ‘Introduction: Receiving Three Mochilas in Colombia: Carrier Bags for Staying With the Trouble Together,’ in The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction (London: Ignota Books, 1996).

Le Guin, ‘The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction’, 1989.

Thu-Van Tran in conversation with Pedro Morais and Magali Nachtergael, video interview, published by Almine Rech Gallery on 20 April 2020: https://www.alminerech.com/artists/325-thu-van-tran.

Bill Gammage, The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines Made Australia (Crows Nest, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin, 2012); Bruce Pascoe, Dark Emu. Black Seeds: Agriculture or Accident? (Broome, Western Australia: Magabala Books, 2014).

Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins, (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2015).

Tran, ‘Thu-Van Tran in conversation with Daria de Beauvais,’ Almine Rech, https://www.alminerech.com/features/7599-thu-van-tran-in-conversation-with-daria-de-beauvais [Interview published in issue 33 of Palais Magazine on the occasion of the exhibition Reclaim the Earth on view at Palais the Tokyo, Paris, 2022]

Victorian Collections (Orbost & District Historical Society), ‘pitchi’, https://victoriancollections.net.au/items/51bbcc4c2162ef16005cf524

Recent museological practices in Australia are shifting to use of new museum label descriptions that return agency to the makers of objects who were indeed once known, but through biases of colonial practice in museums were not regarded worthy of naming and authorship in the historical record.