In Defense of the Misremembered: Orality and the Weather in the Work of Katinka Bock

Itches

“I’m longing for an exhibition whose quietness is regularly disturbed by the agitation of the world outside, the irritations, the discontents, the itches of the times.” So wrote Katinka Bock in an email to twelve of her friends in June of 2019, inviting them to contribute to a newspaper she was planning to publish in collaboration with Thomas Boutoux and Clara Schulmann, as part of her exhibition Commotion in Higienópolis at Lafayette Anticipations in Paris. The idea was that a newsroom would be set up in the exhibition space, and – with an editorial board of local high school and college students – each edition would be produced and printed on-site, within a single day.

In this exhibition, Bock was installing a large-scale sculpture built out of hundreds of copper panels which had originally formed the dome of the Anzeiger-Hochhaus building in Hannover. When the panels of the dome were being replaced, Bock managed to salvage the old ones, which had lived outside for almost a century, oxidising and turning green with verdigris while accruing scratches and imprints from bird claws, the weather, and WWII bomb fragments. Bock is drawn to objects that have been around; surfaces that carry marks of time and exposure. When she learned that the Anzeiger-Hochhaus had once housed the offices of a number of major German newspapers, she decided to also make her exhibition into a newsroom, to try to bring real-time inscriptions of world-exposure – “the itches of the times” – into the exhibition.

Bock is often looking for ways to work with (as she termed it in that 2019 email) the “outside-in and inside-out” of art exhibitions and their surrounding conditions – though sometimes it’s a more subtle intervention. In For your eyes only, parte pelo todo (2019), she exhibited twenty metres of blue fabric that she had left on the rooftop of the Edifício Copan (Copan Building) in São Paulo for a four-month period, so that it would accrue a patina of exposure to the outside elements (sun, wind, rain, pollution), which could then be brought inside. Sometimes she sends her artworks out into the world. A number of sculptures have been left submerged in bodies of water – such as Conversation suspended (2018), which was left at the bottom of the Clyde Estuary in Scotland for nine months, or Junimond (2017), which was deposited into the Atlantic Ocean, near Arcachon Bay in France, indefinitely. For her Zarba Lonsa project in 2015, she arranged swaps with shopkeepers in Aubervilliers, in the northeast of Paris, so that some of her ceramic objects ended up being displayed in store windows in the Quatre-Chemins district. On a number of occasions, Bock has set up a device to collect rainwater from outside one of her exhibitions, directing the water into a pipe running through the gallery, as a little bit of the weather invited in to interrupt the closed-off sanctity of the exhibition space.

Exposure Time

... photographed in the time of what Bock calls the “apnée,” the held breath...

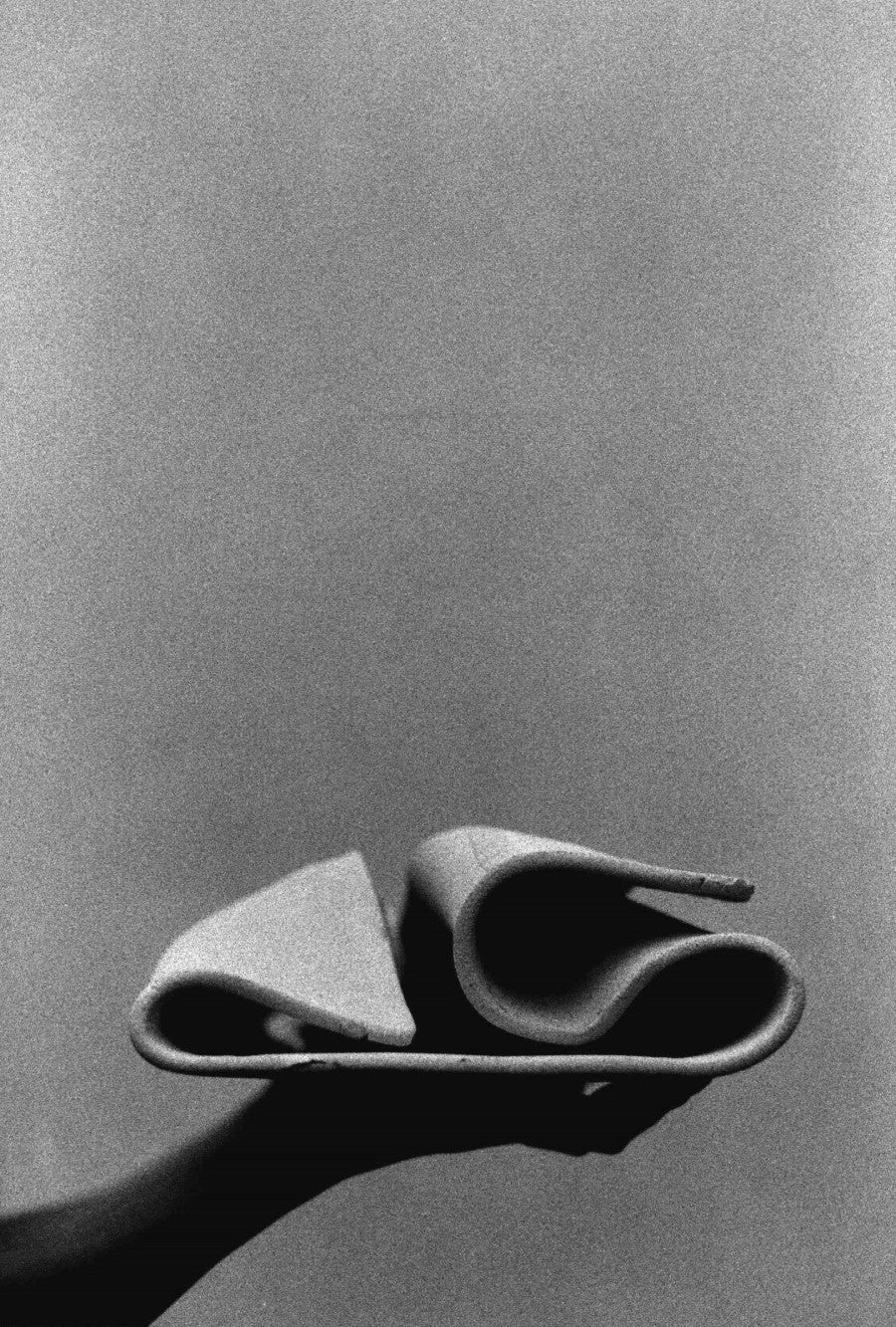

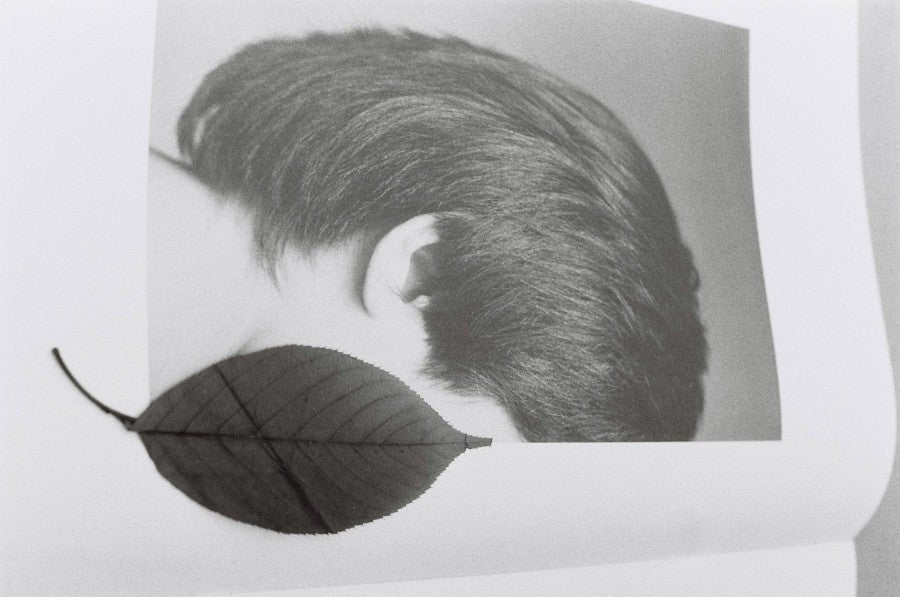

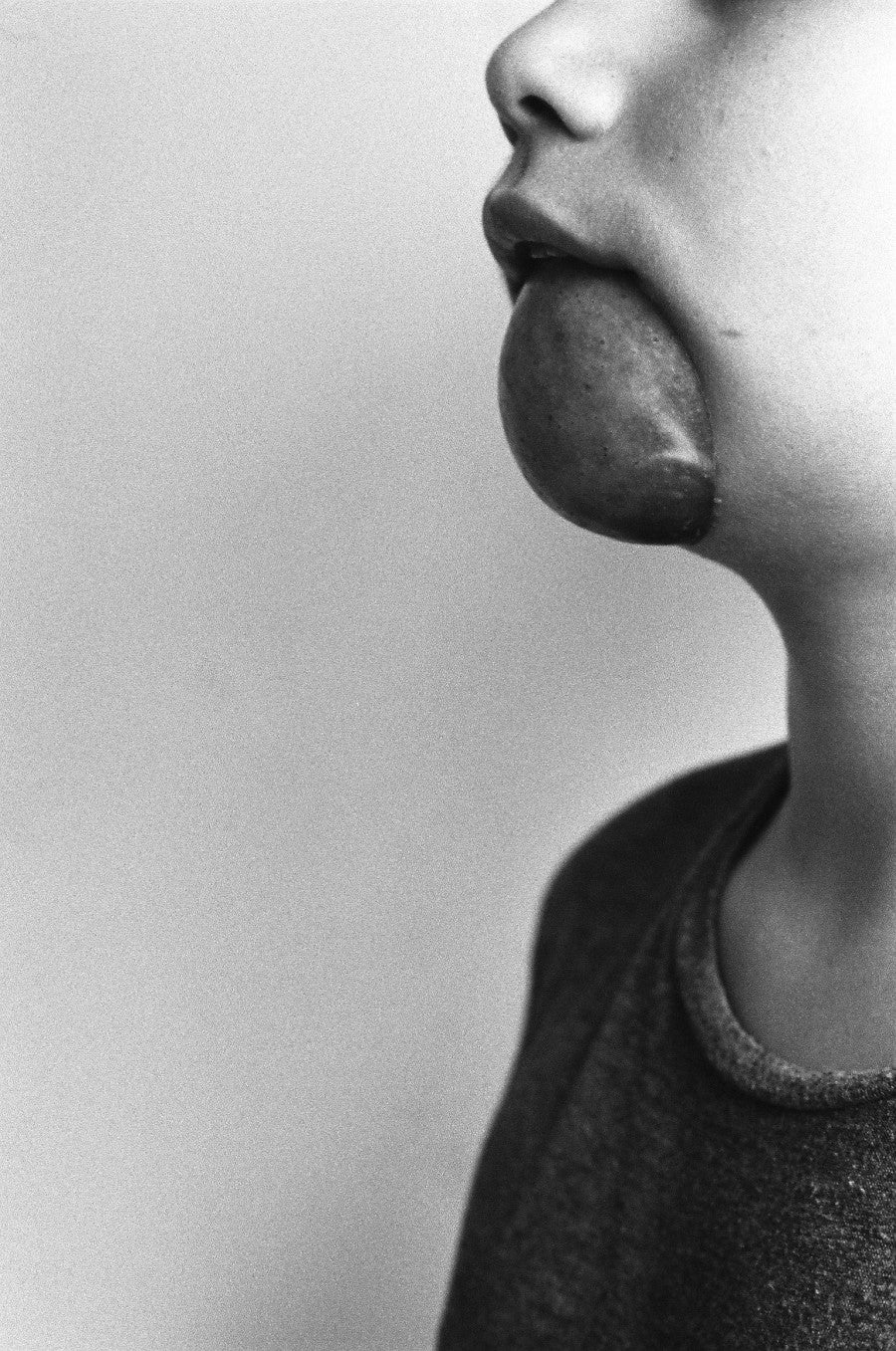

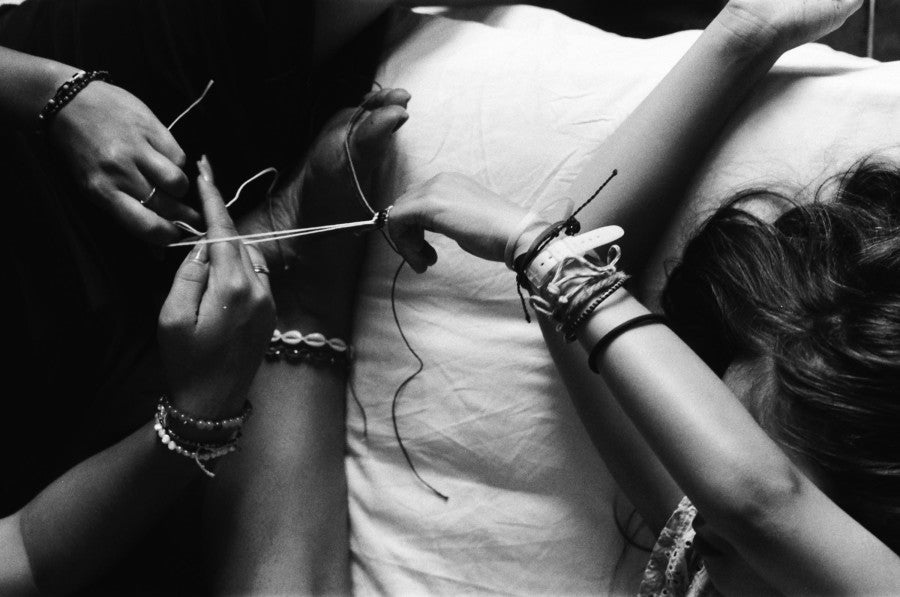

Der Sonnenstich, Bock’s exhibition at Fondation Pernod Ricard, is focused on one particular aspect of the artist’s practice from the last decade or so: her photographs. Bock doesn’t consider herself a photographer per se, but for years, alongside her practice as a sculptor, she has taken pictures on a Pentax K2 35mm camera from the 1970’s, which was given to her by her grandfather. The subjects of her photographs are diverse: a donkey’s ears; shadows; leaves; spoons; butcher shops, especially at the end of the day, when the blood gets washed away from the display cabinets; someone’s ankle imprinted with a pattern of lines after a period of sitting on the grass; items of clothing removed from the body and left crumpled on ground; a tiny crab at the bottom of a coffee cup, with the dregs of coffee ready for a tasseography reading; a moment of intimate stillness when a grasshopper has landed on someone’s shoulder and they pause, so as not to disturb it. Vacuum cleaners come up a lot. Old vacuum cleaners left out on the street in front of apartment buildings in Berlin and Paris, abandoned and waiting for someone to come along and take them away. Vacuum cleaners in gallery spaces, photographed in the time of what Bock calls the “apnée,” the held breath, when the exhibition has been fully installed but it hasn’t opened yet; the floors need to be vacuumed one last time, before the doors open and the exhibition starts to breathe. “What do you like so much about vacuum cleaners?” I asked Bock when I visited her studio in Paris. “Have you ever opened one up and looked inside the bag?” she enthused. “It’s such an intimate and specific portrait of a real time and place; you can read it like an archive.”1

When people come into the frame in Bock’s photographs, they tend to be anonymised. Often, her camera is only interested in close-up details of body parts – especially hands, feet, and necks. If they aren’t cropped out, faces are usually turned away from the lens, or they’re masked by other body parts and found objects. Someone hides underneath their long hair; someone else is obscured by the freshly fried tentacular pancake they hold up in front of their face. Throughout Bock’s photography, objects offer a world of cover and impromptu refuge, as well as possibilities for prosthetic extensions that playfully renegotiate the boundaries of the body.

No Words

Bock’s photographs can be presented within exhibition contexts, but – as with her sculptural objects – the gallery is just one possible, temporary site for them. If you encounter a photograph by Bock in a gallery, it has probably already had a life in the world outside, because an important part of the artist’s photographic practice lies in her experimental approach to circulation. Many of the photographs displayed as part of Der Sonnenstich have appeared previously in Bock’s One of Hundred publications, an ongoing series of self-published newspapers made semiregularly, since 2013, in collaboration with graphic designer Louis Lüthi. Each One of Hundred is produced in an edition of one hundred. They’re always staple-bound, in A3 format, and always without any text accompanying the photographs. No titles, no captions, no names, no dates, no page numbers, no copyright information, no details about the time and place of publication. It’s a self-funded enterprise, and the newspapers are never sold, they are only given as gifts by the artist to friends and people she meets.

Bock doesn’t keep any records of distribution for the One of Hundred, and she doesn’t have a precise memory of exactly what she has given to whom. If a recipient of one of these publications wants to know more, she might talk to them about the selection of photographs or the context of the project, but she doesn’t necessarily have to tell them anything at all. Sometimes an edition is made alongside or in response to a specific project. The first One of Hundred compiled photographs of a concrete floor – with all the traces of contact and exposure that its surface held – in a gallery space where Bock was exhibiting. Other editions have come out of a particular research focus, such as the artist’s time spent observing and interacting with the public areas of Oscar Niemeyer’s Copan Building in São Paulo. My personal favourite is the One of Hundred that compiles documentation around the artist’s Zarba Lonsa project, with photographs of her enigmatic ceramic objects nestling up with the merchandise in stores in Aubervilliers (including clothing and jewellery stores, a butcher and a bakery, grocery and hardware stores, an optician, and stores selling small electronics and wedding goods).

One does not necessarily have to know about the background of the photographs in these publications. By presenting the images as images on their own, without any accompanying text, Bock sends them out into the world with an understanding that images can mean different things at different times to different audiences in different contexts. “I’m interested in the possibilities of an oral kind of distribution,” she tells me.2 The written word can pin images down with fixed associations; in its absence, alternative meanings might open up. Maybe the recipient of a One of Hundred newspaper remembers or half-remembers something Bock told them about it; maybe in the gaps of knowledge, other information and new associations can circulate and accrue orally.

An Oral Kind of Distribution

...that which is learned by heart can live on through collectively embodied memory.

There is a common assumption that writing is more trustworthy and more reliably retrievable than the orally transmitted word. We’re encouraged to get things down in writing in order to make them more official, more legitimate, more binding, more real. But in certain circumstances, the ephemerality of the written word and the possibility of sustained endurance through orality can come to the fore. Let’s take a detour ... In Soviet Russia, there was a group of poets who found themselves out of favour with the regime. Unable to publish their work by any official means, they had to come up with other ways to circulate and archive their poems, and it turned out that orality offered a more secure storage facility than printed matter. Publishing led to an increased risk of being surveilled, blackmailed, exiled. When things were written down, they could be censored, altered, destroyed – but when this group of friends memorised each other’s work by heart,

the poems and the poets could be kept relatively safe.

Without the possibility of going to print, these poets rethought their assumed dependence on it. “M. does not need Gutenberg’s invention” said Anna Akhmatova of her life-long friend Osip Mandelstam, who was exiled for his poetry, but whose poetry was kept alive through the hearts and the tongues of his friends.3 Lydia Chukovskaya described how Akhmatova would write out her own poems on scraps of paper for visitors to recite and memorise, before burning the paper to ashes. “It was like a ritual,” Chukovskaya writes. “Hands, matches, an ashtray. A ritual beautiful and bitter.”4 Against the assumption that orality is more fleeting than writing – its words more susceptible to loss and distortion – this image of Akhmatova burning these scraps of paper is a reminder that the written word can be surprisingly vulnerable and ephemeral, while that which is learned by heart can live on through collectively embodied memory.

Verdigris

These persecuted Russian poets and their practice of committing each other’s poetry to memory has been a frequent point of return in the work of philosopher and playwright Hélène Cixous. In her play Black Sail White Sail (1994), Cixous affirms that the orally constituted archive is not just a stand-in substitute for times when the written word is too dangerous – rather, orality has its own way of working; its own materiality and rhythm; its own epistemological capacities. In Cixous’s rendering, one of the things that happens as these poet friends memorise and recite each other’s work is that the values of neatly-bounded individual possession and authorship start to get messed up. In a scene from Black Sail White Sail that begins with Akhmatova losing her identity card, uncertainty develops around the origin of a poem that she and Nadezhda Yakovlevna Mandelstam both know by heart. Akhmatova is sure that this poem, A Tear, is her own. “I remember each line beading in each one of my veins,” she says.5 But Nadezhda insists that A Tear is Osip Mandelstam’s. While Akhmatova is initially indignant, she eventually concedes that perhaps “My memory... is no longer my memory.”6 Nadezhda later remarks that the origin of a poem is never really traceable. “Who knows,” she says to Akhmatova, “Tear is perhaps a little bit born of you with Osip.”7

Cixous affirms the possibility of a kind of intersubjectivity – even an intercorporeality – developing among this group of friends. “They memorised each other’s poems, gave breath to each other, made each other’s heart beat,” she writes. “They lent each other an ear, gave each other their own blood.”8 In the scene described above, the confusion that arises between the poets about what belongs to whom could be attributed to a shortcoming of the oral archive; without the written record, it’s harder to divide up ownership and authorship in the same way. But this same blurriness could also be a source of relief – a means of liberating the poems out of the confines of clearly divided-up individual authorship and into the abundance of relationality. When Cixous’s Akhmatova worries that her internalisation of Mandelstam’s poem as her own might be a sign of madness, Nadezhda suggests that “Maybe it’s love that’s overflowing.”9

Bock’s decision to exclude the written word from her One of Hundred publications, in favour of the possibilities of oral distribution, obviously differs from this situation in important respects: unlike these poets, she’s not working against a backdrop of totalitarian censorship and political persecution. But whether or not orality is turned to out of necessity, as a means of survival, it involves a certain relinquishing of any desire for water-tight control, and an acceptance that things will not remain bound to one’s original authorial intentions. While a physical exhibition of photographs will typically exist for a specific duration at a specific location, the time-place of printed matter is far more unruly, and Bock enjoys the idea that her publications might have extended afterlives as they circulate beyond the limits of her knowledge or control, towards undetermined futures.

Where have all these wordless newspapers ended up, and what have they done along the way? Was one of them looked at on a long-distance train journey, or maybe accidently left behind on the platform? Encountered in the middle of the night by a dim lamp, or carried up a hill and laid out in the sun, with ants crawling over the pages? Stuffed into carry-on luggage, skimmed over breakfast, forgotten in a bookshelf and returned to only years later when it’s time to move out of the apartment? Does the person moving out of their apartment recall that this was a gift from Katinka Bock? Do they want to treat the publication as an art object and keep it in pristine condition, or will they embrace the marks of time and exposure that accrue on its surfaces (the fading colours, the increasing brittleness of the newsprint paper)? Will they leave their One of Hundred edition behind, or maybe use some of the pages as wrapping paper for gifts? Have they remembered or misremembered any particular details about the images?

The Goddess of Forgetfulness

I think the statue was actually made as some kind of tribute to forgetting...

It was the middle of August when I visited Bock’s studio in Paris. It’s late-October now, and I think I recall some things quite clearly, but a lot has become murky. I remember that we had planned to go for lunch at a café called Le Zéphyr in Belleville, but when we arrived, we realised they were closed for the summer break. The city was quiet, and hot, and the trees were bursting with bright, mid-summer green leaves. Now, two and a half months later, the leaves on the trees where I am are losing all their green. When there’s a lot of sunlight around, the trees make chlorophyll to aid in photosynthesis, but when summer ends, the chlorophyll leaves and the leaves start to show the crispy yellows and reds that have been there all along, lying in wait within the glossy green.

I keep thinking about a sculpture that was in Bock’s studio the day we met. A life-sized cast bronze figure – green with verdigris (the hue of exposure belonging to the copper component of the bronze) – standing behind us as we were looking at something else. It had a quietly intense presence, but we only spoke about it briefly at the end of my visit, and my memory of the details is foggy. I think the statue was actually made as some kind of tribute to forgetting... I email the artist and ask her to refresh my memory. Was it a statue of Lethe, the Greek goddess of oblivion and forgetfulness, who was associated with the River Lethe, the river of lost memories? Not quite; I’ve misremembered. Bock tells me the sculpture is called Amnésie. She’s not Lethe, but she is indeed supposed to be an embodiment of forgetting.

Attached to Bock’s email reply are some photos for me to look at of this monument to amnesia (a word that comes from “a” for not + “mnesi” for remembering). It’s not really a monument; the figure recalls monumentality in her bronze materiality and her full body of armour, but she’s hollow on the inside: her body is a vessel, and the only thing she memorialises is the value of forgetting. She has no triumphant horse, no pedestal to elevate her, no permanent position in public space, and – as with the artist’s photographs in the One of Hundred newspapers – no caption or plaque explaining her importance. “I really like it when information gets lost,” Bock tells me. “I like the free space of not knowing. Forgetting can open up the possibility of other modes of remembering... Forgetting offers us a chance to do things again, but differently.”

Conversation with the author, August 14, 2022.

Conversation with the author, August 14, 2022.

Mandelstam, Nadezhda, Hope Against Hope: A Memoir, translated by Max Hayward (New York: Atheneum, 1983) p. 376.

The Penguin Book of Russian Poetry (introduction). The Akhmatova Journals: Volume 1: 1938-1941 (Evanston, Northwestern University Press, 2002).

Cixous, Hélène, “Voile Noire Voile Blanche / Black Sail White Sail” in New Literary History (Spring, 1994, Vol. 25, No. 2) pp. 222-354; p. 265.

Cixous, Hélène, “Voile Noire Voile Blanche / Black Sail White Sail” p. 265.

Cixous, Hélène, “Voile Noire Voile Blanche / Black Sail White Sail” p. 269.

Cixous, Hélène, Readings: The Poetics of Blanchot, Joyce, Kafka, Kleist, Lispector, and Tsvetayeva (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1991) p. 116.

Cixous, Hélène, “Voile Noire Voile Blanche / Black Sail White Sail” p. 267.