Extreme non-violence. A portrait beyond the photographer.

Joanna Warsza with guest contributions by Muhammad Ali, Flaka Haliti and Jay Jordan.

Sunday afternoon

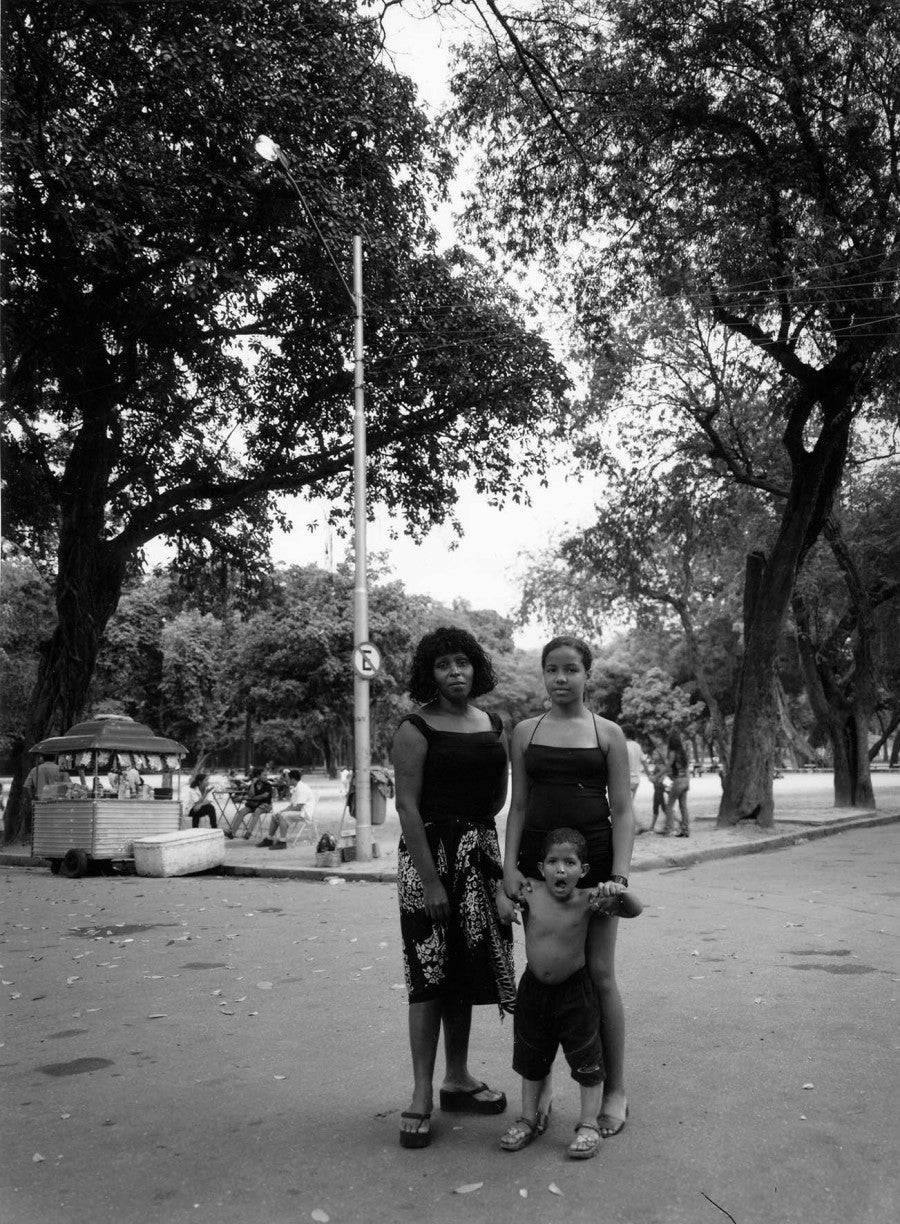

There is a saying that a portrait tells more about the person behind the camera than the one who is photographed. A single picture is capable of showing the ecology and multitude of relations happening inside and outside of the frame, before and after the photograph has been taken. When I look at French artist Bruno Serralongue’s series ‘Sunday afternoon’ made in Brazil over twenty years ago, from 1999-2000, I wonder: what does the work say about the artist himself and his use of the medium?

‘Sunday afternoon’ is a series of photographs performed in a park in Rio de Janeiro. Back in those days, before mobile phones, local photographers offered to take photos of the passers-by – families, children, couples. This is a gesture and a service seemingly archaic today, yet driven by a similar desire to capture a walk, a kiss, a hug, a family gathering, a shared moment, a farewell. Many local snappers were strolling the parks to earn money by making those weekend portraits. Serralongue went along and, learning this local, often amateur habit, also became a Sunday photographer for a day. Instead of taking money, he asked to keep the negatives of each portrait, while the sitter walked away with the positive. As he recalls: “I try to be attentive to how the medium is performed in various countries and cultures, how it is used by non-professionals and how photography happens. Everyone has their own way. I tried this method in Rio, but not for too long, not to take away someone else’s job.”

What kinds of relations emanate from people depicted in the shots from Rio? Whom do we see on paper? Which relationship can be traced or felt between the two sides of the camera and around it? There is a mother with her five-year old daughter, a teenager with a Walkman, a hugging couple, a man who has been jogging, a person in a work uniform, two women accompanied by a laughing child, another mother and a daughter and then a small girl alone. They all pose for the camera, they all awkwardly try to stand still, they often attempt to smile. The pictures are taken in a place where two paths meet, at a crossroad which is sometimes empty, sometimes packed. There is no special setup, it is almost always accidental; sometimes the small kiosk around the corner is busy, other times deserted. All seem relaxed, although a bit anxious about the camera pointing at them. Their faces paint a mixture of shyness and joy, anxiety and curiosity, serenity and uncertainty – feelings I also experienced when encountering Bruno Serralongue for the first time in Paris in September 2021 on our ‘blind date’, paired by TextWork.

The Force of Non-violence

Non-violence is employed here as an artistic strategy, as an attitude, as a mode of work and life

There is something salient about ‘Sunday afternoon’, a less-known series of Serralongue’s oeuvre and, at the same time, less characteristic of his work. Namely, the people depicted have deliberately chosen to be looked at, to be seen, to have their photo taken, or, as one says in English, using a somewhat militaristic term, ‘captured’. One feels the two-side consent and unspoken agreement rooted in the vernacular use of the medium and in the thrill of the encounter. One can also feel a bridge between a local culture and an external gaze in a way which is respectful and not asymmetrical. There is perhaps an experience of ‘deborderisation’ in the words of the philosopher Achille Mbembe1. That is, a semantic bridge between from where you speak and with whom you speak, the connections you build between you and them, with curiosity and respect, without mere appropriation. Another thing both visible and hidden in plain sight in those weekend photographs, and perhaps in all of Serralongue’s practice, is the touch of what I would call ‘extreme non-violence’. Non-violence is employed here as an artistic strategy, as an attitude, as a mode of work and life, as a leading thread of the artist’s photographic path, whose camera obscura is too heavy to run after the news, and who sometimes needs ten years to develop and exhibit the resulting photos. And they often become almost extreme in their non-spectacularity, in their function not to picture the event, but rather display the everyday structures behind them.

The concept of non-violence has of course long been a political strategy of not causing harm to others, be it people, animals or the environment. Many political and social movements, some of which Serralongue decided to join or follow, choose nonviolent principles to achieve political and social change, to practise civil resistance or disobedience as a way of pushing forwards against the still prevalent militaristic, colonial, violent mindset of many Western societies. The political scientist Judith Butler in their recent book The Force of Non-violence (2020) argues that the ethic of non-violence must be implemented within the broader political struggle for social equality to exist. Butler understands it not as a passive attitude, but an ethical position and an active practice needed in the political field. It is not a search for naïve consensus, but rather for a language which, despite all differences, conflicts, misunderstanding and possible hostility, would allow humans and non-humans to peacefully coexist. Such understood non-violence, claims the philosopher, is found in movements for social transformation that defend the concept of interdependency as the basis for social and political equality: an “ethico-political bind.”2

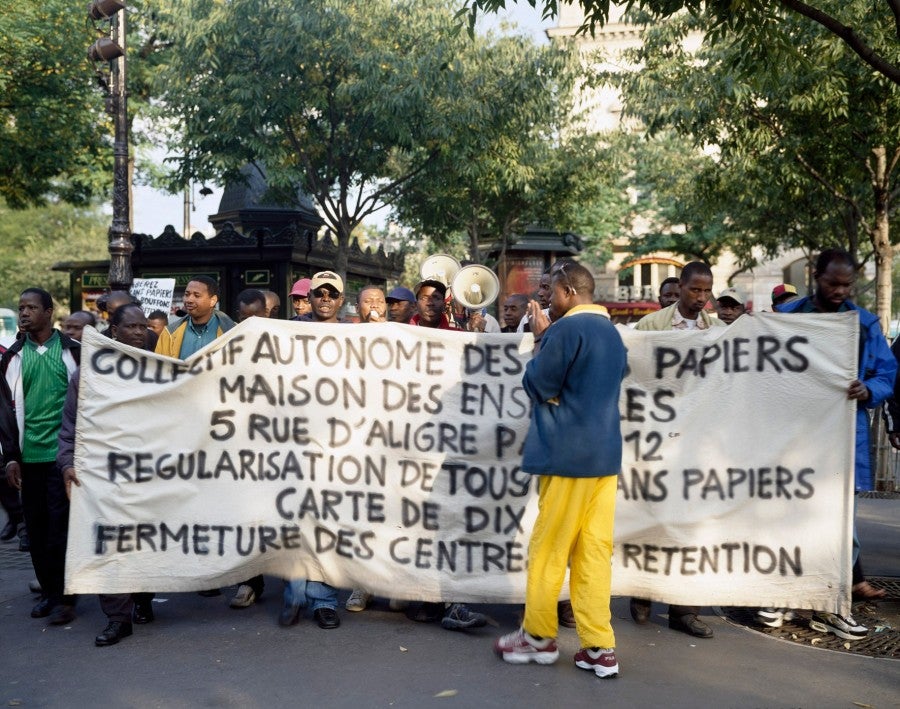

Since the mid nineties, Serralongue followed and embedded himself in various activist struggles and organisations, which he documented in a long process as they often unfolded over several years. One of the first series he produced was ‘Les manifestations’ (1995), capturing Paris strikes and street demonstrations against the reform of the retirement system. He followed with the series ‘Encuentro, Chiapas’ (1996) taken in Mexico during the Intergalactical Meeting against Neoliberalism and for Humanity, at the invitation of the Zapatista Indians. From 2001-03, he turned up at every gathering of a Parisian group of immigrant workers denied legal recognition, resulting in a series of only 45 photos: ‘Manifestation du collectif de sans papiers de la maison des ensembles, place du Châtelet, Paris’ (2001-2003). He was also present at The World Summit for Sustainable Development that took place in Johannesburg in 2002, which led to the series ‘Earth Summit’ (2002) and at the counter-meeting during the World Summit on the Information Society in Geneva in 2003 and in Tunis in 2005, resulting in two series of work. There followed his participation at the World Social Forum in Mumbai in 2004, and the series ‘La Otra’ in 2006, a report on the Mexican electoral campaign for the presidential elections led by Subcomandante Marcos, spokesperson for the Zapatista guerrilla. Since 2006, Serralongue has photographed refugees and their everyday life in camps of The Calais ‘Jungle’, who were waiting for a possible passage to Great Britain3. He was also present between 2014 and 2018 at the Zone à Défendre in Notre-Dame-des-Landes in France, a successfully occupied territory against an airport infrastructure project, and very recently he took part in Saccage 2024, an on-going initiative criticizing the gentrifying force of the Olympics in Paris and its region.

For many years, he worked against the hegemonic language of photo reporting, the structural racism perpetuated in seemingly objective Western newspaper news, often photographing the scene of an event a day after, and keeping a position of, what he calls, “solidarity with a distance.”4 He has long worked against the presupposition that physical proximity brings one closer to the given context. He rather chooses to exhaust and expand the gaze in his purposely ‘not very eventful’ point of view. The camera he uses is a classical camera obscura, a photographic chamber. The photos can not be reworked and they take time to be made. For example in the 15 years of his presence in The Calais Jungle, Serralongue took only 89 pictures. His work is almost like the far opposite of Instagram stories: there are very few of them and they do not disappear. “My photos are not meant for the internet, I don’t have a website. They are meant for gallery walls, and they come back on display every couple of years.”

Solidaric with a distance

"I am against the logic of capturing just one moment.”

As an artist – with his “own Agence France Presse,” as he says – Serralongue has been working against what he calls “the picture in our heads whenever we go somewhere”. There is, for example, a prevalent mediatic image of refugee camps on Lesbos or in Calais, the war in Kosovo or the occupation of ZAD, but his work consequently produces a counter-philosophy to the omnipresent press images, which “strangle us and fill up our heads”.5 Through hegemonic mediatisation “we end up living in a fiction,” says Serralongue. While introducing his work at the opening of his exhibition at Jeu de Paume in 2010, he joked that “the reality is here, it is the fiction which is outside”.6

When we met in Paris, I asked Serralongue to describe not only his relationship to non-violent struggles, but also his potential definition of nonviolent photography: how to produce images which are conscious of asymmetries, conflicts and yet rather than reproducing them, try out another visual regime. In fact, what Butler’s nonviolent research brings to light is that for centuries, the whole paradigm of contemporary, mostly-Western, life (and perhaps art) has been violence-based from the colonial, to the patriarchal and modernist horizons. Bruno explains: “I have integrated myself in those activist groups, also because I share their ethics. I want to practise non-violence against certain dominant photographic methodologies that impose brutality. Not only are they meant to capture the cruellest, most spectacular moment, but they also cultivate the press photographer’s attitude of being close without closeness, or coming and going without deeper interest and respect. I am against the logic of capturing just one moment.”

In contrast, Serralongue’s works can seem unspectacular and random – be it following the naturalists at ZAD, the declaration of independence of Kosovo or his coverage of alterglobalist movements – and yet they are taken from the point of empathy, kindness and perhaps shyness to come closer. They are performative in how they seek to eradicate the semantic, symbolic or physical forcefulness. “I try to be as honest as I can with the people I am photographing, taking a position, but being non-invasive.” He later adds. They seem underwhelming, sometimes strange, empty, not eventful. Instead of an event, they tend to present the everyday support structures that led to them, like people preparing folders for a meeting, or a woman who fell asleep at a desk. Perhaps this is how a non-violent image looks.

Photography as a genre is deeply embedded in that model of ubiquitous conquering, possessing, depriving. Historically, photography has been both a tool for activism, documenting struggles, visions, politics and the unconscious but, even more so, it has been responsible for serving extraction, colonization and various forms of oppression, consequences of which still linger today. Photography thus can be a violent act, a separation between subjects and photographer, and an imposition of a patronising gaze and representation. At the same time, it can be seen as a mediator, as a potential carrier of resilience and reconciliation, a proof of violence, a token in regaining dignity. Serralongue is a contemporary artist who works to investigate how the language of art, and in his case anti-reportage photography, can become a way of unlearning the existing forms and norms of cultural domination and imperialism. Although he too, as everyone, is implicated.

No one is the sole signatory to the event of photography

Ariella Azoulay, a prolific anti-imperialist, anti-racist scholar of photography, and a curator and researcher of the political ontology of the medium, has been analyzing its ethical status, the blind spots of its scholarship, its performative force and the concept of the ‘event of photography’ since the early 2000s. By the ‘event of photography’, especially in recent times, in which almost everyone is in possession of a camera, Azoulay understands “an event which might take place as the encounter with a camera, with a photograph or with the mere knowledge that a photograph has been (or might have been) produced. This possibility might be troubling, pleasing, threatening, damaging, soothing and even reassuring. Obviously, the feelings of all those partaking in the event are not aroused by this possibility. Photography is an event that always takes place among people. Out of this event a photograph might possibly be produced. The photograph produced, or not produced, at this event is a rich document that might prove helpful in attempts to reconstruct something of the encounter for all of those who took part in it. It is unique in that no one can claim a sovereign position from which to rule what, of this encounter, will be inscribed in the photograph. When such a photograph is inaccessible, other sources can be used that bear witness to the photography-event. One can use one’s civil imagination to complete the multiple points of view that the photograph might have recorded, had it been produced.”7 For Azoulay, the photograph is just one of several outcomes of the photographic event, alongside the encounter, the relations being built but also the text and the interpretation that grows around it.

She also argues that the medium of photography is, first and foremost, a particular set of relations between individuals and the governing powers, and on the other hand, always a form of relation among those who take part. She advocates for a political ontology of photography where a civil, non-extractivist, post-sovereign contract is possible, reducing the asymmetries between those behind the lens and those in front, be it on political or personal levels: “Photography is not just operated by people, it also operates upon them. The camera is no longer just seen as a tool in the hands of its user, but as an object that creates powerful forms of commotion and communion. The camera generates events other than the photographs anticipated as coming into being through its mediation. (…) Human subjects, occupying different roles in the event of photography, do play one or another part in it, but the encounter between them is never entirely the sole control of any one of them: no one is the sole signatory to the event of photography.”8

Three predominant threads emerge when I look at Serralongue’s main line of work: portraying First Nations and Indigenous people in their militant campaigns, following various ecological and social movements, and finally, accompanying migrants on their routes such as the sans-papiers in Paris or the Jungle in Calais. All those ‘currents’ employ the method of an anti-reportage, in which a photographer, rather than accumulating the best snaps of the event, shares the feeling of being and growing with the movement, as well as reveals the structure and the invisible labour that constructed and enabled it.9 I am sticking again to his exception, the ‘Sunday afternoon’ series, presumably innocent and banal pictures from a park in Rio de Janeiro, and I wonder: how are those photos liberated from the spectacular? Is there a respectful relationship? Can a relationship be asymmetrical and ethical at the same time? And what parameters need to be in place for a photographer to be able to borrow from others’ stories? I also see calmness.

Polyphonic responses: Introducing the guests

Is it possible not to fall in the traps of identity politics and yet recognize the need for privileging a situated perspective...?

Inspired by Azoulay’s proposed event of the photography as a situation always taking part between multiple sides, expanding beyond the moment of the release of the shutter, and the mere authorship of Serralongue as the artist and myself as the writer, I thought of a small curatorial experiment that would decentre this essay and open it up to more voices that symbolically or physically partook in the context that surrounded some of the artist’s series. During our Paris conversation, there was something that remained troubling for me, namely the silent perspectives of those depicted in the artist’s work. I believe it is of benefit to Serralongue’s work, and to the relationships he builds, to welcome a discursive response from the other side of the camera. I thus invited three artists who were direct witnesses or participants in some of the situations pictured in the photographer’s recent portfolio.

My guests have been asked to look back and respond to fragments from three series of works by Serralongue – one from Kosovo in 2009, one made in the French ZAD mentioned earlier, between 2015-2017, and one photographed on Lesbos in 2017, from a lived, often risk-involved perspective.

I first reached out to Flaka Haliti, an artist who was in her teenage years as the conflict broke out, and who, along with many others, had to flee the country on the refugee trains towards Macedonia. The post-war landscape, the NATO presence in a newly declared country, the visual grammar of the public space, all present in Serralongue’s series, have also been her concerns as an artist.

I also asked for a comment from Jay Jordan, a long-term activist of the aforementioned ZAD, a person who has for a long time struggled to bridge art and activism, topics also dear to Serralongue.

Finally I reached out to Muhammad Ali, a Kurdish artist from Syria based in Stockholm. In 2015, along with many others, he fled the war, and made his way illegally by boat to Greece, and then to Sweden. He might have been one of the refugees passing by the island during Serralongue’s stay.

It seemed like a collective reading of the images would enable seeing a larger picture, to unpack the pertinent questions of our time, namely how to speak for each other, how to borrow each other’s stories, and how images can mediate this process. Is it possible not to fall in the traps of identity politics and yet recognize the need for privileging a situated perspective around the questions of who has a right to speak for whom? Flaka Haliti, Jay Jordan and Muhammad Ali share a reading, rooted and marked by a lived experience, in the following email exchanges:

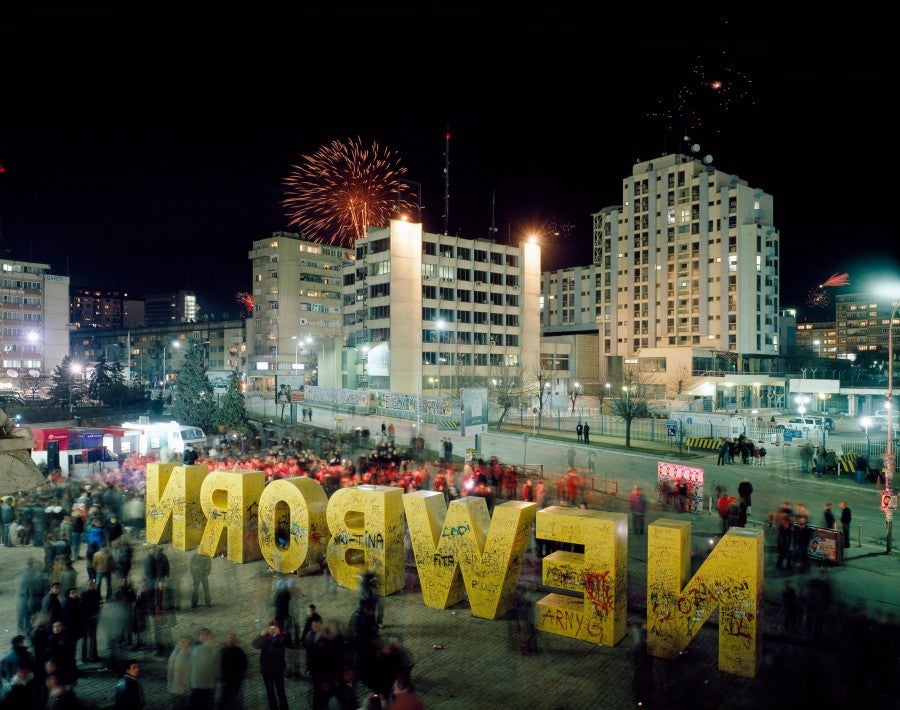

A response to ‘Kosovo’, 2009-present, by Flaka Haliti, an artist originally from Prishtina, based in Munich

On 28 October 2021, at 10:07:37, Flaka Haliti wrote:

Every one of the scenes I look at in this series is somehow poor, which makes them intriguing. They look random, but when you hold them for longer and look more carefully you start to notice things and dilemmas of everyday life in post-war Kosovo: a fading image of the peaceful leader overtaken by former militia and banks – two leading institutions of growth and development. You feel the charged atmosphere of the military, which is supposed to bring peace and stability. “They are here to stay” – famously said Albin Kurti, back then a peace activist and today a Prime Minister. “They are here to stay in order to keep the crises stable and maintain the tension of the status quo.” Those pictures show what the everyday is made of and the impossible questions of what is next, the feeling of cruel optimism and the cold calculation of what can be given or taken from you. I almost want to laugh when I see the photograph of the billboard promoting ten years of stability, with two boys, maybe around ten years old below them.

For more than two decades after the war, the publicity on promoting peace building and a democratic state in Kosovo was very much imposed by external Western actors keen to manage Kosovo’s image while imposing an identity that no longer could hold itself. This process was demonstrated clearly by specially launching a massive number of billboards that appeared all around Kosovo from NATO (KFOR) and UNMIK. The communication on these billboards delivered a persuasive political message. As Rancière would call it, it is an image of a twofold dilemma: “the question of their origin (and consequently their truth content) and the question of their end or purpose, the uses they are put to and the effect they result in”.

Serralongue’s pictures of Kosovar billboards capture, in an uncanny way, how the images are being used to serve a certain purpose to affect the self-perception of the Kosovar society, how those images have been omnipresent and invasive to our bodies, culture and politics.

Furthermore, I also try to decode in the series what is crucial in my own work: the power positions in the communication between locals and internationals. What kind of aesthetic language do they use, including the usage of the city’s architecture as a tool. How did this affect the locals and what kind of stereotypes have been reinforced through the different visual communication tools? As Dragana Jovanovic argues, in the post-war-reconstruction, the vision was lacking because the international community was the sole policy-maker and, hence, excluded local instances in the decision-making process and refused the local power and responsibility, which resulted not only in the lack of local control, but also in limited challenges to the status quo.

If you look again at the images celebrating ten years of stability with the helicopters, the sunset, the Western aesthetics, these images almost serve the UN staff members’ dilemma. At the same time, the UN in fact lacked the full authority to formulate policy and merely mediated the policy-making process – yet they were identified with current policy and hence bore the brunt of the local population’s criticism. What we see somewhere in the background is that the local trust in international policy making is fading out with the time…

‘Comptes-rendus photographiques des sorties des Naturalistes en lutte sur la ZAD de Notre-Dame-des-Landes’, 2015-17. A comment by Jay Jordan, an artist, author and activist, and co-founder of The Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination and an inhabitant of ZAD, France.

the capitalocene has opened up a new front, radically against representation, a front where artists no longer describe the world but transform it together with others.

On 5 November 2021, at 23:40:36, Jay Jordan wrote:

These images were taken during a walk by Les Naturalistes en Lutte, one of the many extraordinary creative forms of resistance that took place on the 1650 hectares of wetlands and farmland that French politicians declared “lost to the republic”, but which are known by those who inhabit it as la ZAD (the ‘zone to defend’). This autonomous zone is a messy but extraordinary canvas of commoning, illegally occupying the territory earmarked for building an infernal climate-burning international airport. In 2018, the forty-year-long struggle snatched an incredible victory and the construction of the world-wrecking machine was cancelled.

The airport was meant to be an ‘ecological’ one, an oxymoron of criminal proportions. Using ecological compensation, which turns the living into objects to be traded on a market, the multinational Vinci and the French government who are building the airport thought that their green-capitalist lie would dissuade resistance. But the opposite was true. In the spectrum of tactics ranging from sabotage to building farms in the way of the runways, mass tractor blockades to rioting, les Naturalistes en Lutte entangled their knowledge as scientists and studiers of the living with the resistance movement.

For four years, they took people on walks across the wetlands and did an in depth inventory of all the living species that would be destroyed by the airport building. These photos were taken on one of these inventories. Now, all the knowledge harvested has created an extraordinary cartography of the living on this once threatened land, which is now the most detailed study of biodiversity in Europe (bar the special natural parks, mountain ranges etc.).

The fight against the airport was won because of such a culture of resistance, in which people applied their skills, from electricians helping the squatters pirate electricity to doctors coming during the violent evictions, from locals bringing dry socks to lawyers offering free services. And what do artists do as a gesture of cultural resistance? Do we continue to make ‘pictures’ of the resistance? Do we continue to show the world to people? That time is over, the capitalocene has opened up a new front, radically against representation, a front where artists no longer describe the world but transform it together with others. Many deserting artists live on the ZAD, deciding to put their lives and bodies in the way of the death machines rather than feeding the logic of extractivism, turning their life into an art of resistance.

The airport was another extractivist project. Art that takes value from a movement and then gives that value to the artists’ career or to maintaining the art market, rather than back to the original communities, can be similar. How does contemporary photography give back to the movements it took images from? How does it become reciprocal rather than extractivist? Perhaps it can’t. (…)10

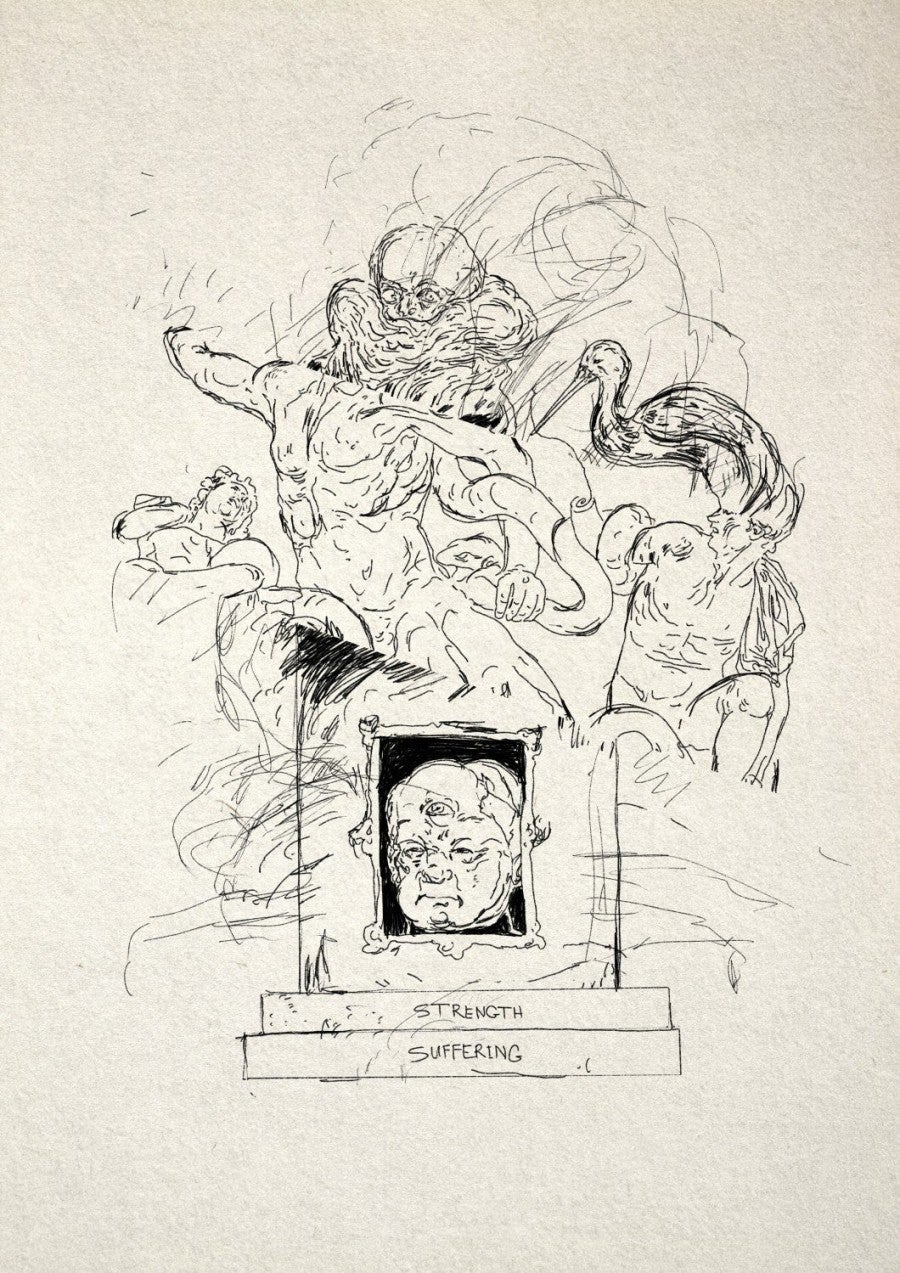

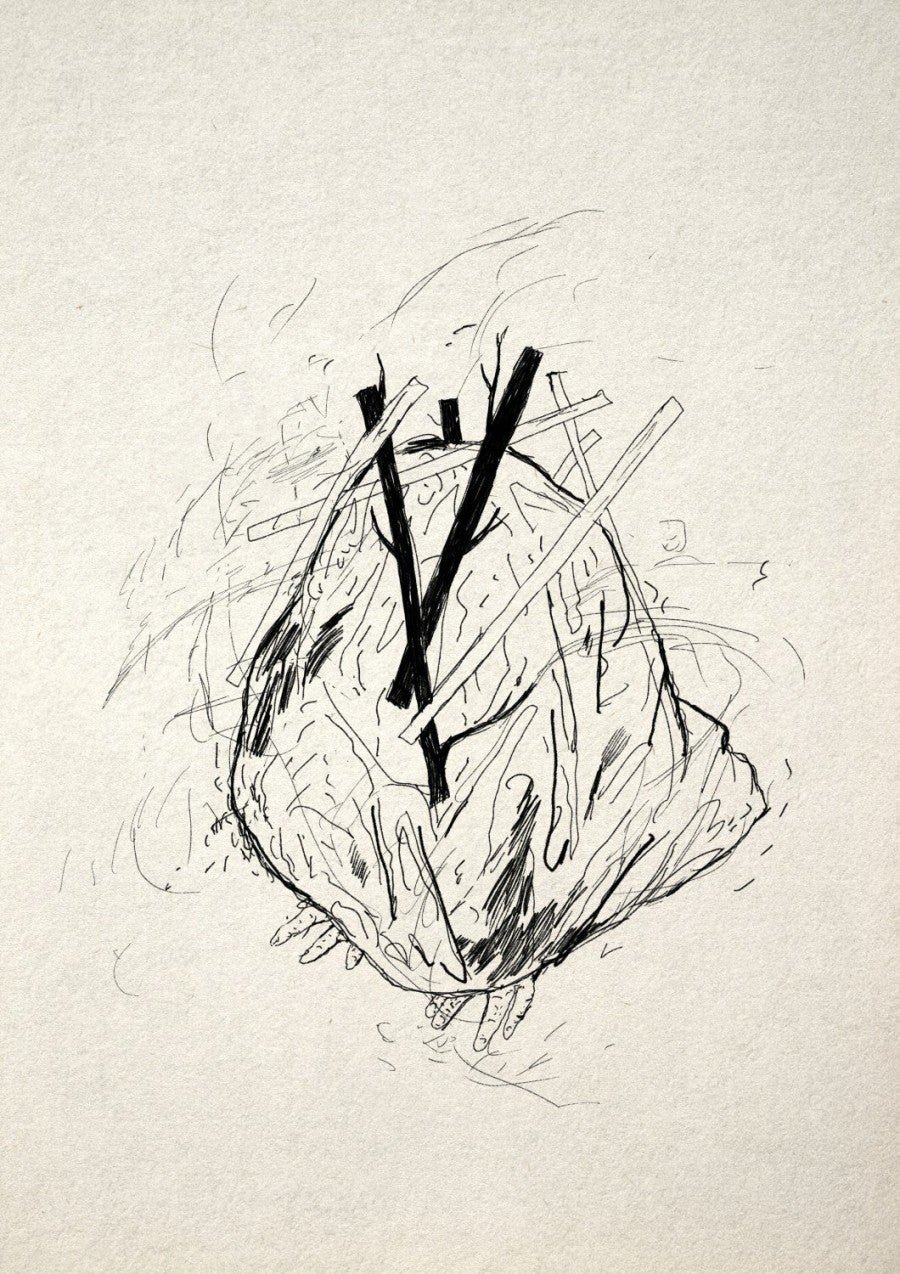

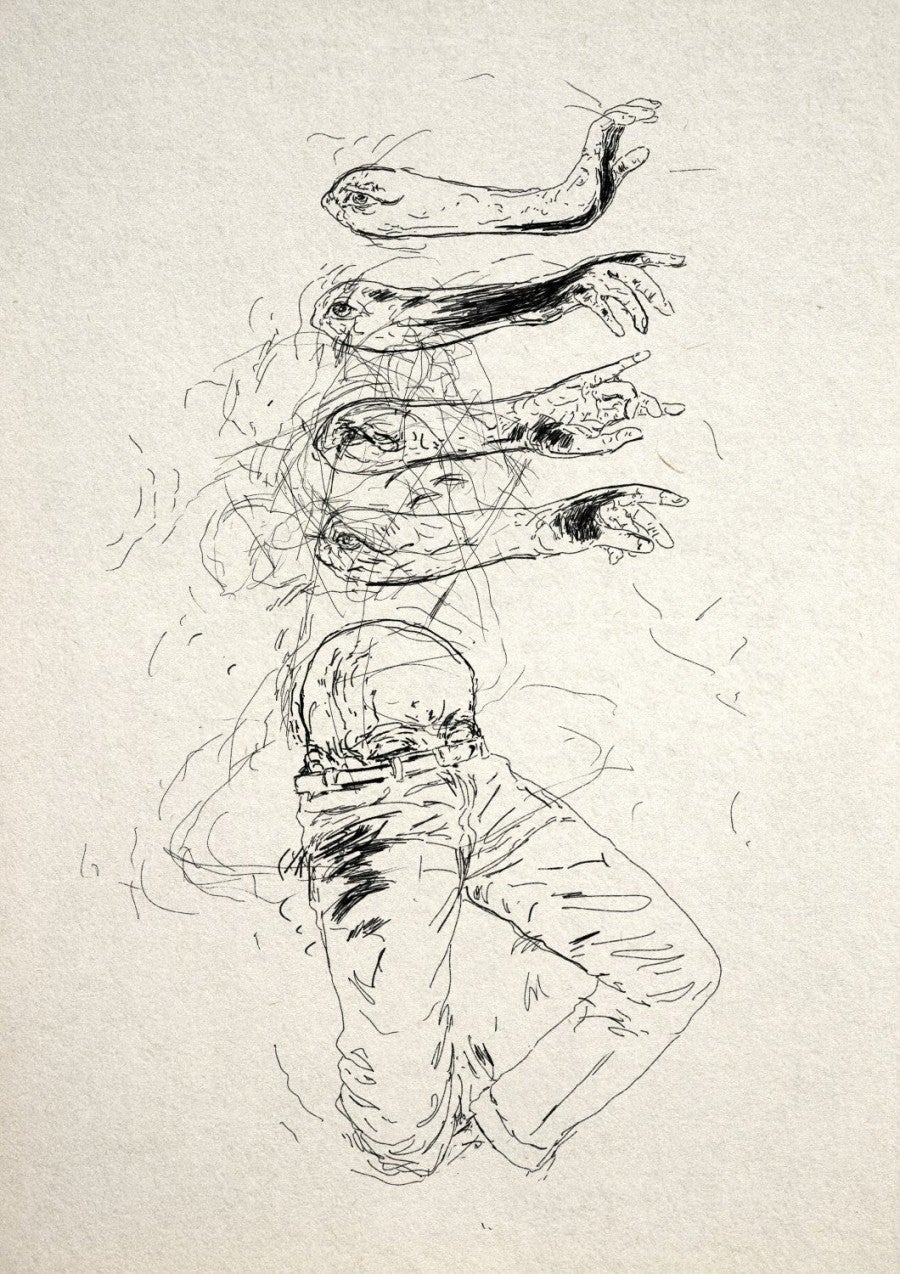

A response to ‘Lesbos’, 2017 by Muhammad Ali, an artist from Syria based in Stockholm

On 26 Oct 2021, at 09:40, Muhammad Ali wrote:

Dear Joanna,

Thank you for inviting me. I received a few invitations in the last few years to do interviews about this experience in Lesbos but I always have difficulties explaining through words. I like the idea behind the interview, so I can answer through drawings, but not text. Please check the attached digital drawings.My best, Muhammad Ali

If needed, I will redo the same photograph throughout the years

For Haliti, the non-spectacularity and ‘poverty’ in the images makes them interesting, showing the dull reality outside of the frame. For Jordan, the position from which one speaks has to be always articulated in an activist manner. For Ali, there are yet no words to comment on the photographic series of an illegal passage to Europe. These polyphonic responses bring to light the questions between art and activism. How can those fields empower, rather than disempower, each other? Photography has never been more present, more prevalent, more involved in the construction of the political. Every year, millions of photographs circulate on the planet. And with their growing number, there seems to be more and more to do and to undo for us, the spectators, the readers, the analyzers, the social media scrollers, the producers and consumers.

We need photography that dismantles that violent, military-driven visual grammar, which proposes other interdependent, ‘anti-imperial’ visual languages

Azoulay helps again when she advocates for the visual citizenship or the citizenry of photography.11 When one sees refugees’ jackets on Lesbos, massive evacuations from Kosovo, or the struggles of ZAD against the polluting neoliberal infrastructure, one can hopefully connect it to the larger ‘we’, to ourselves as implicated subjects, since everyone contributes in some way to those events. We need photography that dismantles that violent, military-driven visual grammar, which proposes other interdependent, ‘anti-imperial’ visual languages, another potential history. “My camera is heavy and slows me down,” says Serralongue about the large-format camera he uses for his projects. “Most of my time is not spent taking photos but looking around and thinking how I can move” and “if needed, I will redo the same photo throughout the years”. One of the installations in his upcoming exhibition at Le Plateau, Fonds Régional d’Art Contemporain in Paris will feature a slideshow of various demonstrations which is as long as the duration of the show, so practically only the gallery guards will witness it in its entirety. Taking time is one way of resisting the accumulation of events, the push to permanently catch or capture something, to impose a gaze, to take selfies or curate social media accounts. And taking Sunday photographs is another. A few contemporary artists, such as Bruno Serralongue, are allies in this process, his work being a small step towards extreme non-violence.

These series can be seen in the publication Bruno Serralongue resulting from his exhibitions Feux de Camp at Jeu de Paume in Paris, La Virreina Centre de la Imatge in Barcelona, and Wiels in Brussels, published by JPRIRingier Kunstverlag AG, 2010.

The artist in conversation with the author, Paris, 23 September 2021.

The artist in conversation with the author, ibid.

Ariella Azoulay, Civil Imagination: Political Ontology of Photography, Verso Books, 2012, p.15.

As a reference: many scholars and critics, such as Philippe Bazin, Marta Gili or Dirk Snauwaert wrote extensively about those series.

This comment opens a whole new chapter of debate about the symbolic value and the relation between art and activism, the terms and conditions of the circulation of artworks and the questions of an ethical exchange between the fields, far beyond Serralongue’s work. Those pertinent issues would need to be addressed in another essay. Thus Jay Jordan's comment is left here open.