1. The process of « glomming » or « grokking » on to an artist’s interests, habits and preoccupations always fascinates me. It might begin because some of her concerns seem to match some of mine or — on the contrary — because she seems to inhabit a fascinatingly different world. By the act of paying attention to her work I glean or guess the artist’s original acts of attention to the world. There is something beautiful in my ignorance about an artist (because it leaves space for my personal fantasies and needs), but also something beautiful about the gradual eradication of that ignorance, a process this monograph will try to reproduce in the manner of a slow zoom towards the work of Anne Bourse.

2. Repetition and variation — the principles of musical composition — are present in the work of a visual artist. What does she repeat, and what does she vary? Is it obsession which draws her again and again to certain themes and motifs, or merely habit? Like music, an art career unfolds in time. Time may also be present in a single work, if only by extrapolation: we imagine the labour that has gone into it.

3. It’s extraordinary — and perhaps a measure of contemporary visual art’s brief to be both utterly eclectic and obscurely prestigious — that a collection of very personal, almost whimsical details can end up representing a nation. I think of Sophie Calle’s show Take Care of Yourself, which occupied the French pavilion at the 2007 Venice Biennale. It was based on a single email Calle had received from a lover, yet it ended up representing, in a sense, the values of the French Republic. In how many other professions could you leverage something so oblique and so personal into something so frontal and public? It’s like amplifying a sigh into a reveille.

4. When I turn to a work in order to reconstruct — like an archeologist or a criminologist — the artist’s fascinations and intentions, isn’t it possible that I am simply spinning a skein of fiction, a story that suits my own personal purposes? Anxious about this — and betraying, perhaps, our culture’s prejudice towards the verbal rather than the visual — I move on to supplementary materials: didactic texts on gallery pasteboard, museum catalogues, statements by curators, monographs, critical reviews, presentations by the artist herself.

What is instantly understood might be invaluable to advertising, but is probably useless to art.

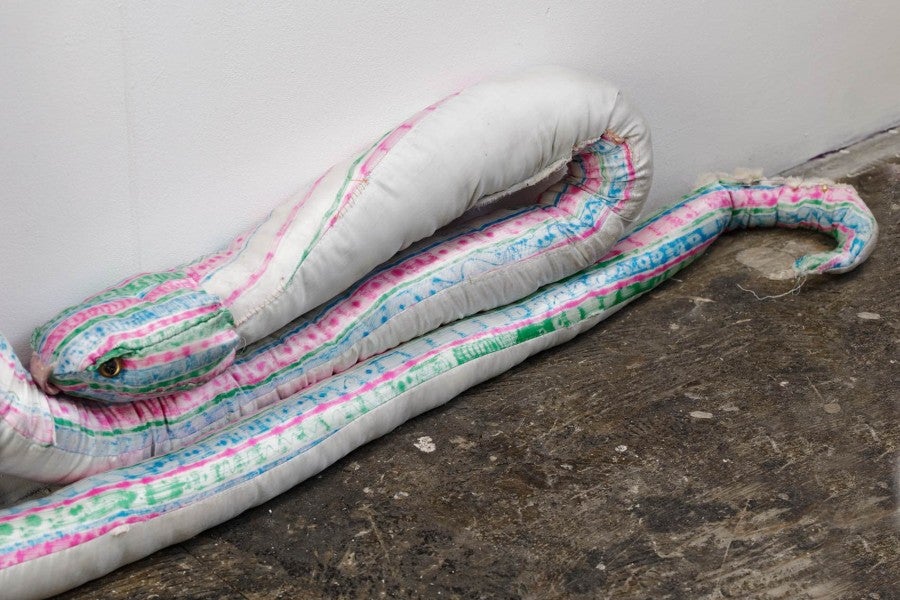

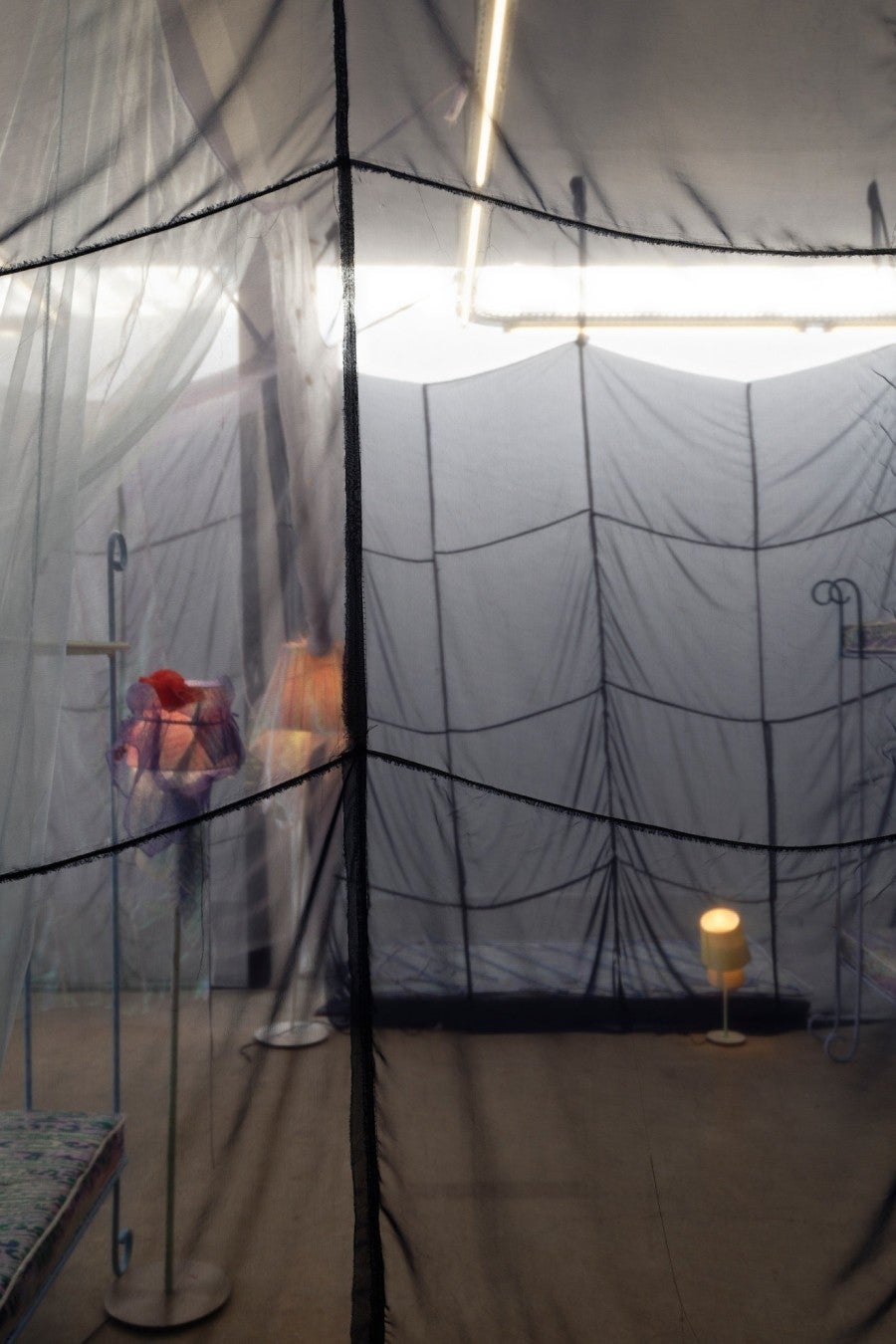

5. The first work of Anne Bourse I ever saw was an installation in the Palais de Tokyo exhibition Future, Former, Fugitive: A French Scene. (And there’s the Calle paradox again: being fugitive may be mapped somehow to being French, just as, at a biennial, personal and quirky works can take on national significance.) The Palais de Tokyo show ran from October 16th 2019 to January 5th 2020 — during what we might now call ‘the twilight of the carefree era’. The work was called Chaque après-midi je me demande ce que tu fais ce soir quand le jour est presque fini (Every afternoon I wonder what you are doing this evening when the day is nearly over). There was a brown carpet, a series of lamps, both vertical and horizontal, with stands both short and long, and several foam mattresses either lying flat or propped against the walls. A long kapok-stuffed snake curved across the carpet, and handmade clothes were suspended from the walls. Pastel colours — combinations of aquamarine and lavender — dominated.

6. This installation — the « bedroom » — has a quiet presence in my memory. Unlike the lightbox of perfumes by Fabienne Audéoud or the snouty glass-painted beasts of Carlotta Bailly-Borg, it didn’t prompt me to reach for my iPhone to snap photos for my Tumblr page. Casting my mind back, I think I was distracted by the minor anxieties of a museum visitor unsure of what he is and isn’t allowed to touch: « Can I walk on the brown carpet? Should I stroke the snake? Have I strayed onto the set of a sitcom? »

7. In retrospect — thinking of that snake — I realise that some of the amniotic, amnesiac atmosphere of the garden of Eden might have been tugging at and drugging me. It felt in that room as if some kind of Eden had been conjured via a series of furniture hacks.

8. The fact that this installation didn’t lend itself to the punchline immediacy of a social media timeline does not, of course, diminish it; if anything, quite the contrary. Good art, as Duchamp liked to say, requires delay1. As in a satisfying game, there should be difficulty, challenge, puzzle, even perplexity. That which can frustrate me, the psychiatrist Adam Phillips once noted, is also that which can satisfy me2. Art should not offer merely those immediate satisfactions Duchamp called « retinal ». Nor should it preach from an open hymn sheet, no matter how righteous. What is instantly understood might be invaluable to advertising, but is probably useless to art.

9. When, much later, I began delving into the supplementary materials around Anne Bourse’s work, I was intrigued to discover a certain tactical subtlety, an elusiveness. Browsing at gallery websites, I scribbled some notes: « fictional characters… lack of ideology… nothing to understand… not dutiful… appropriation, stealing from beggars… making books, magazines… love letters from Shklovsky… »3 Just as the curators intended them to, these fragmentary clues began to pique my interest.

10. In my own writing and art performance I’ve been particularly interested in persona and appropriation. I’ve also had a fascination with the making of ersatz commercial forms like magazines and clothes, a theme which crops up again and again in Bourse’s work. We also have Berlin in common: after graduating from the Ecole nationale supérieure des beaux-arts in Lyon, Bourse moved to Berlin and — with a group of friends — rented an enormous warehouse in the Weisensee district.

11. It had been my intention to travel from Athens to Paris in March 2021 to see two Anne Bourse exhibitions, one a solo show at Galerie Crèvecoeur, the other a group show at Le Plateau (Frac Île-de-France). The pandemic made this journey impossible, but Anne was able to guide me remotely around the Crèvecoeur show — entitled Different Times, Different Paul — using her iPhone. In this first personal contact between us she seemed as engagingly shy and endearingly nervous as she is in the YouTube video in which she presents her work to a Basque art school, rummaging at random through JPEGs on her laptop desktop.

12. Seeing the exhibition in this way, I was struck by the multidisciplinary quality of her work, its ability to make something painterly with three dimensional installations and something conceptual from decorative elements. There’s also something satisfyingly paradoxical about how Anne Bourse creates a grand unity — in the form of an environment — from a series of personal obsessions. Large gauze walls hang from the gallery ceiling, reminding me superficially of the tentlike environments of South Korean artist Do Ho Suh. Both artists use suspended fabric to subdivide and define the gallery space, although Do Ho Suh’s work is much more detailed, based on memories of specific rooms and apartments. These walls create a room within a room, a warmer area in the icy white cube. Later, Anne tells me that these suspended forms were inspired from Charlotte Perriand’s Japanese mosquito nets.

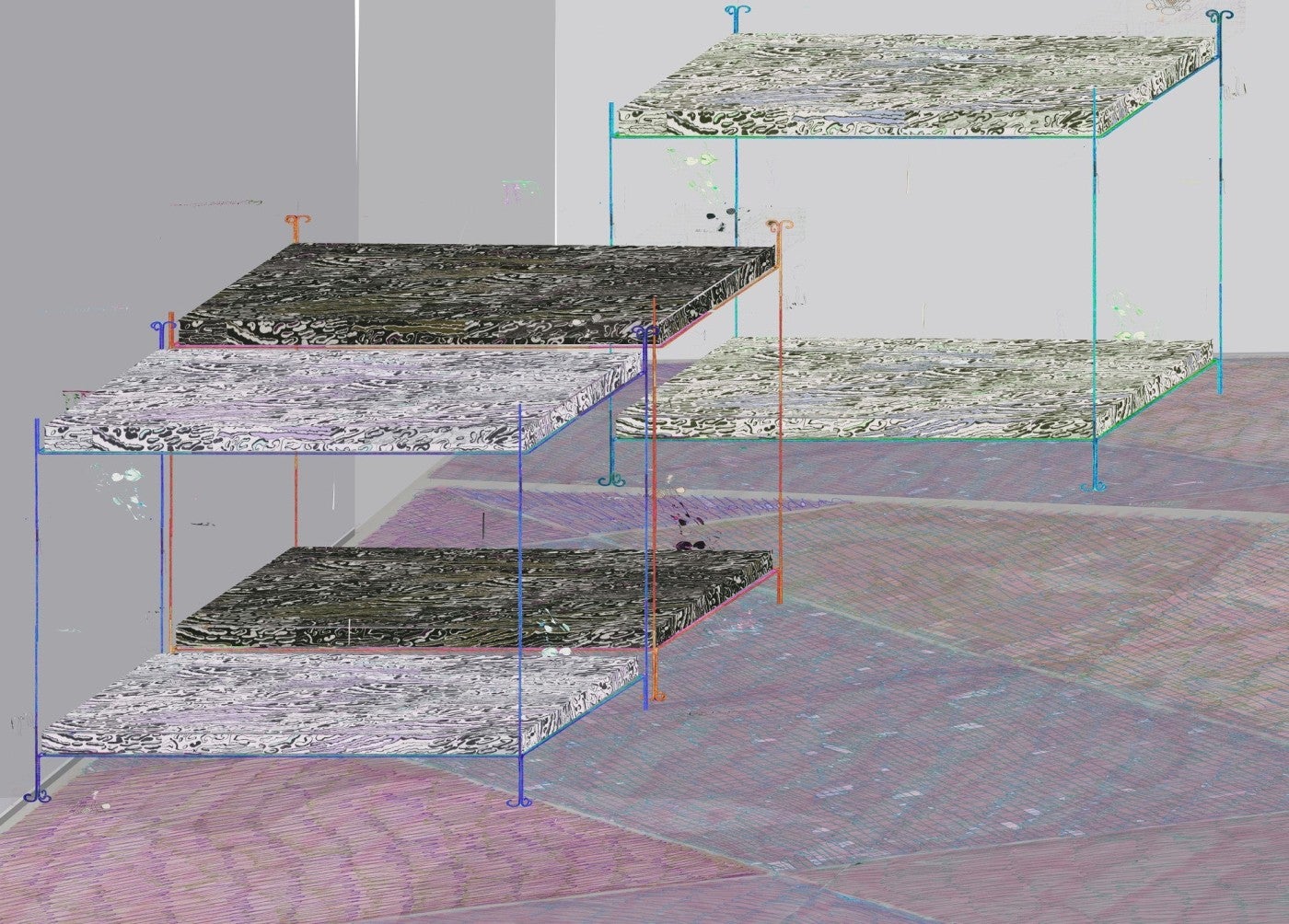

to see...in Anne Bourse's embrace of decorative and functional elements, her refusal to separate art and craft.

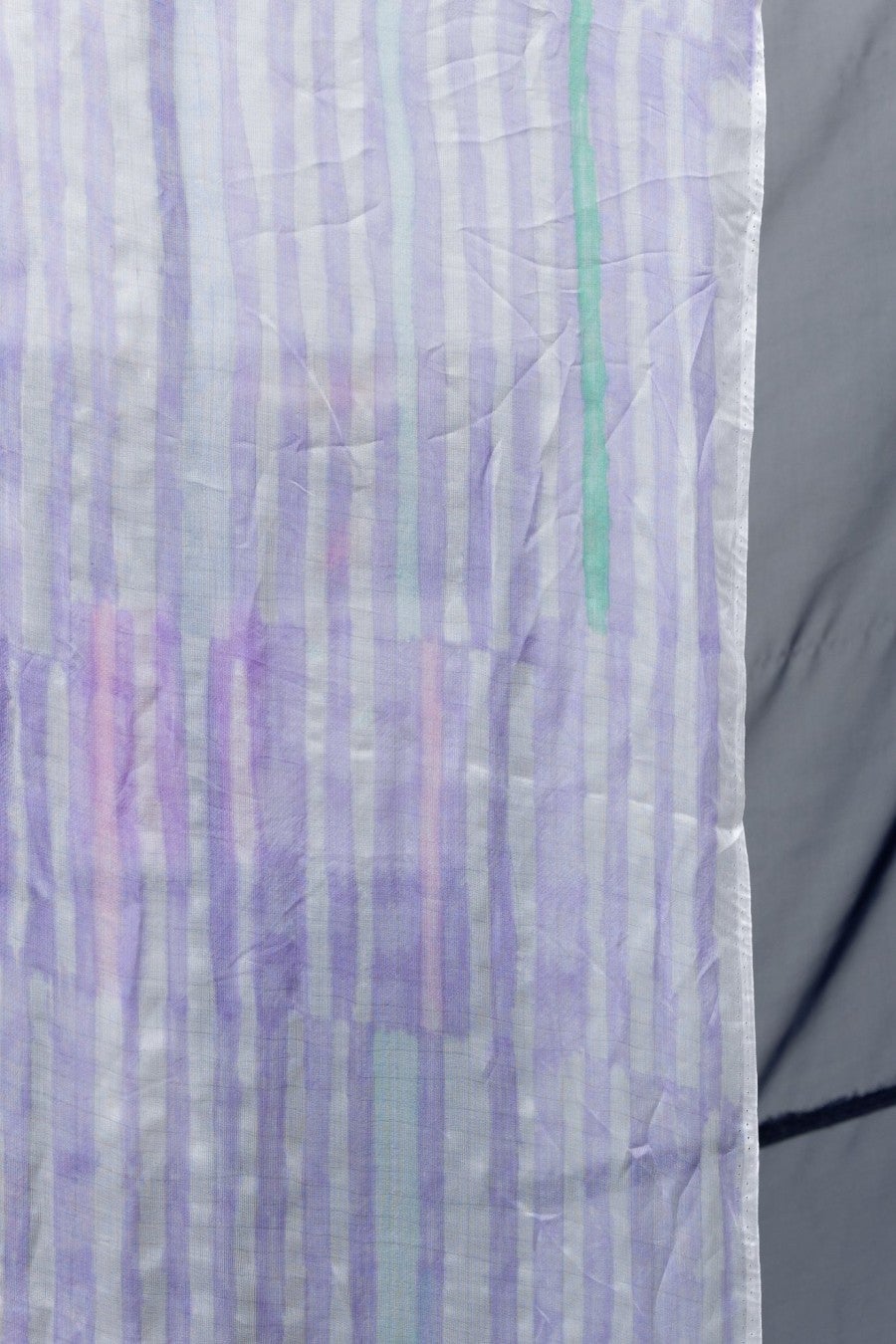

13. Bed frames punctuate the space, simple iron forms with curlicues at either end, decorative flourishes which somehow remind me of the work of Raoul Dufy, a painter whose visual gestures invaded homewares of all kinds in the postwar years. On these frames lie the hand-made mattresses which have become an Anne Bourse signature, painted, the artist told me, with designs taken from a leopardskin skirt fabric that a friend purchased in a second-hand store in Tokyo.

14. The Dufy comparison — which Anne Bourse appreciates — leads to a conversation about the Nabis, the group of French fin-de-siècle painters which included Bonnard, Vuillard and Vallotton. Anne Bourse declares an affinity with these artists, who adopted a flatness of colour and an austere sensuality from the Japanese woodblock prints known as Ukiyo-e. I find myself surprisingly refreshed and enlightened by this reference, and remember how, as a teenager, I bought a book of Vallotton’s prints. These stark and yet sensual domestic scenes were influenced by the Hokusai woodblock prints Vallotton saw at the Paris Universal Exposition of 1889. It’s somehow pleasing to see the ripples of this influence still spreading through Paris 130 years later, and to see a similar Asian influence at work in Anne Bourse’s embrace of decorative and functional elements, her refusal to separate art and craft.

15. Splashes of red and purple dotted across the bed installations somehow make me think also of Matisse’s work, and the 1911 painting L’Atelier Rouge in particular. This womblike scene of the artist’s studio at Issy-les-Moulineaux was influenced by non-Western art in the form of Islamic pieces Matisse saw on a trip to Spain, but the striking thing about it is that, in a sense, it’s really a painting of an installation avant la lettre: chairs, plants, plates, crayons, a set of drawers, a clock, bowls and vases are set in the vibrant field of red, with paintings and frames stacked on the floor or hung on the walls. If an installation can be « painterly », a painting can be « installation-like ».

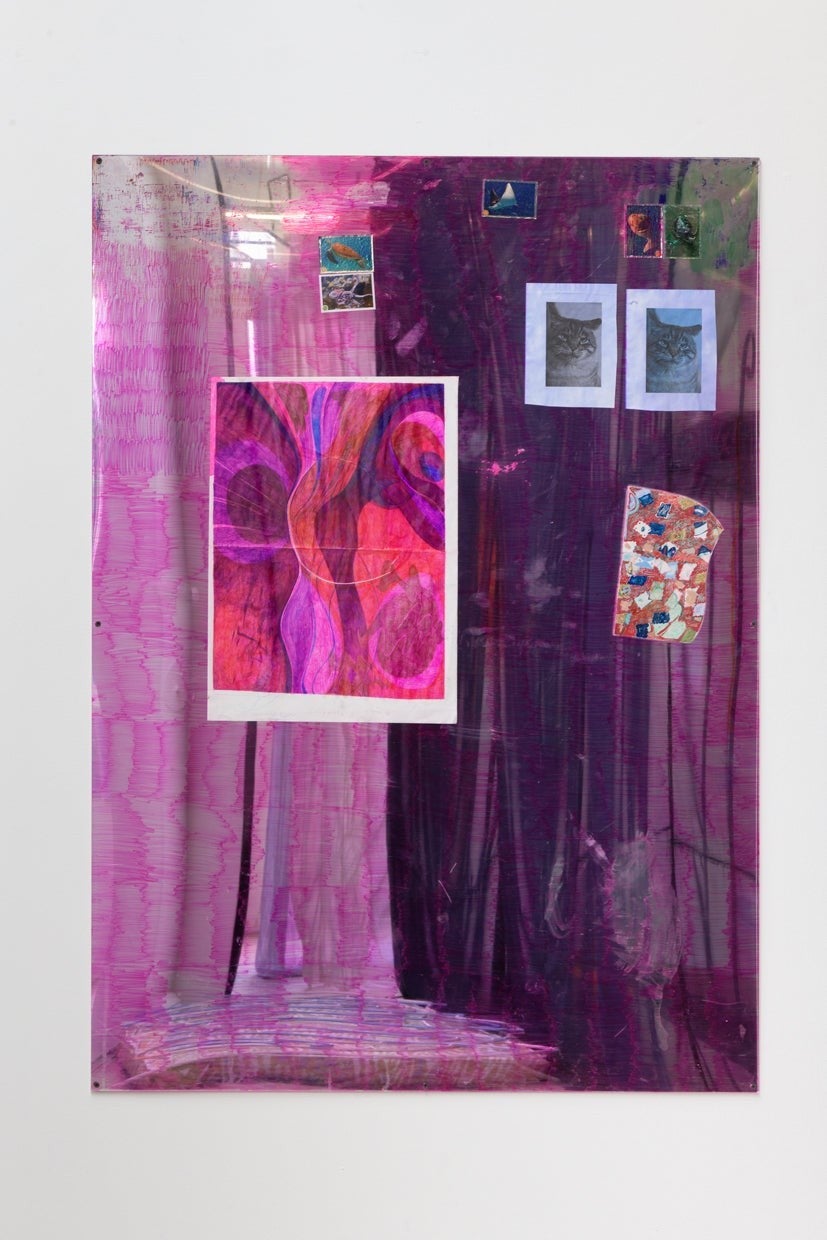

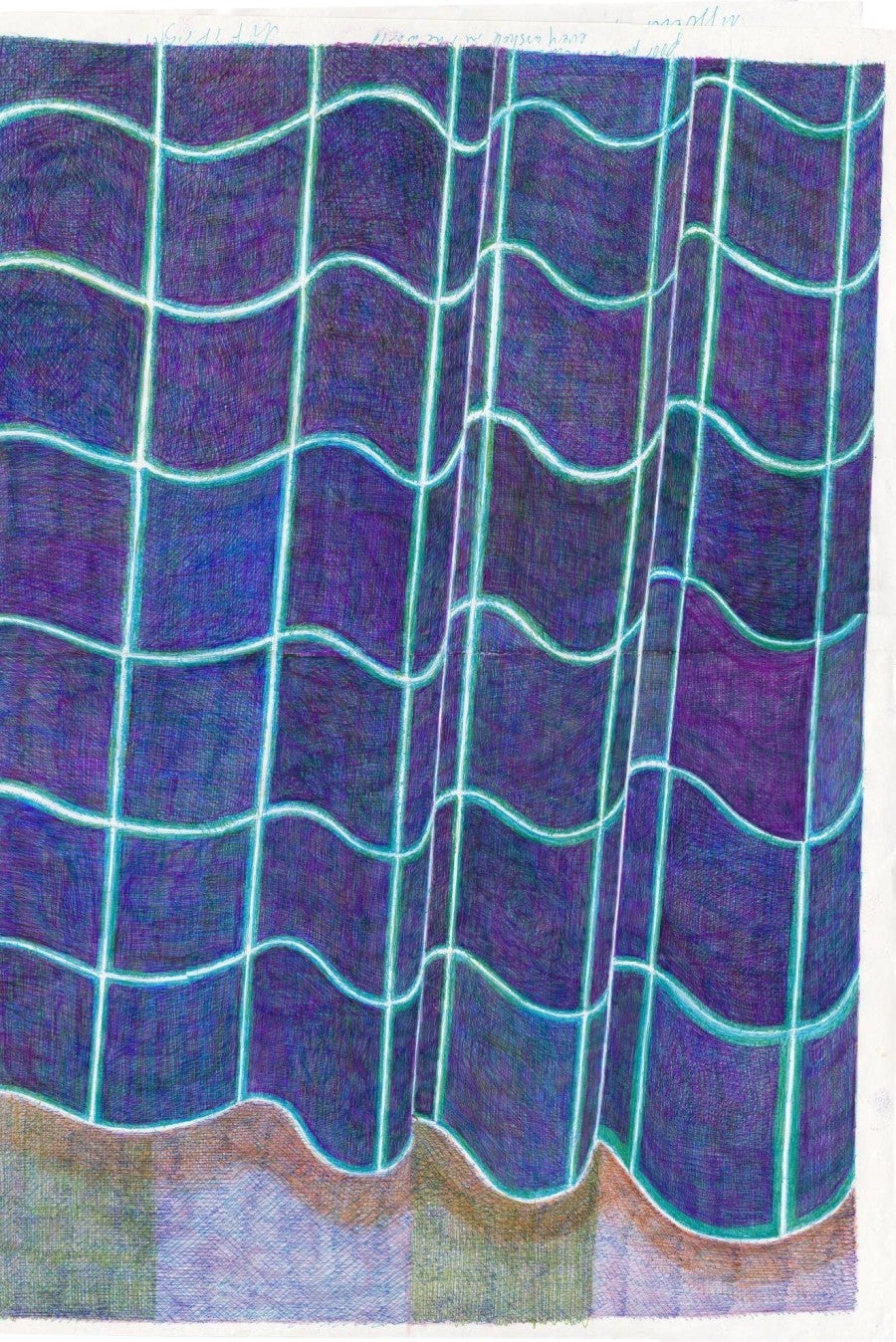

16. I want to linger on the « womblike » quality of L’Atelier Rouge, because it’s something I feel from the work of Anne Bourse too. One feels enveloped by her installations, they feel inviting and protective, full of comfort. They are cocoons, spaces for introverted fantasia, and I feel that this protective sensuality is important. There’s a complete absence of confrontation, aggression, machismo. Instead one is lured into something healing, sensual and soft.

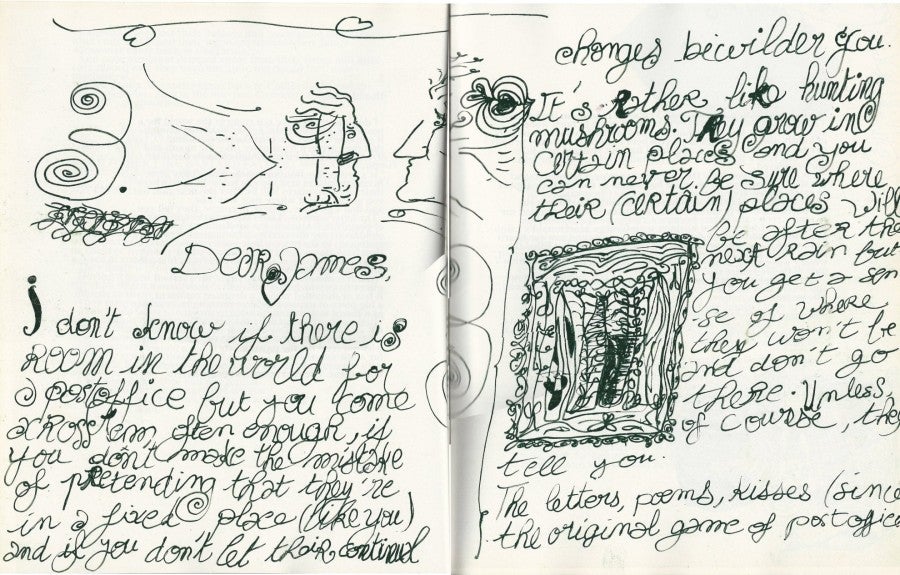

17. The element of fantasia continues in the wall-mounted works at the gallery, in which large panels of pink or purple felt-penned plexiglass host pages of glossy Xerox paper, or wavy forms in shades of aquamarine. These well-chosen complementary colours have been rendered laboriously in ballpoint pen. In both the sheets of coated paper and the imagined act of repetitive doodling (almost nunlike in its patient devotion) a performative, craftlike element enters the work, a dimension of imagined time which adds value almost in the same way that grinding computers do to bitcoin: « What hard work that must have been! » we exclaim, and perhaps begin to think of the work of Agnes Martin, whose arid mathematical repetitions cannot entirely hide an imagined life of satisfying seclusion in a cocoon of personal ritual.

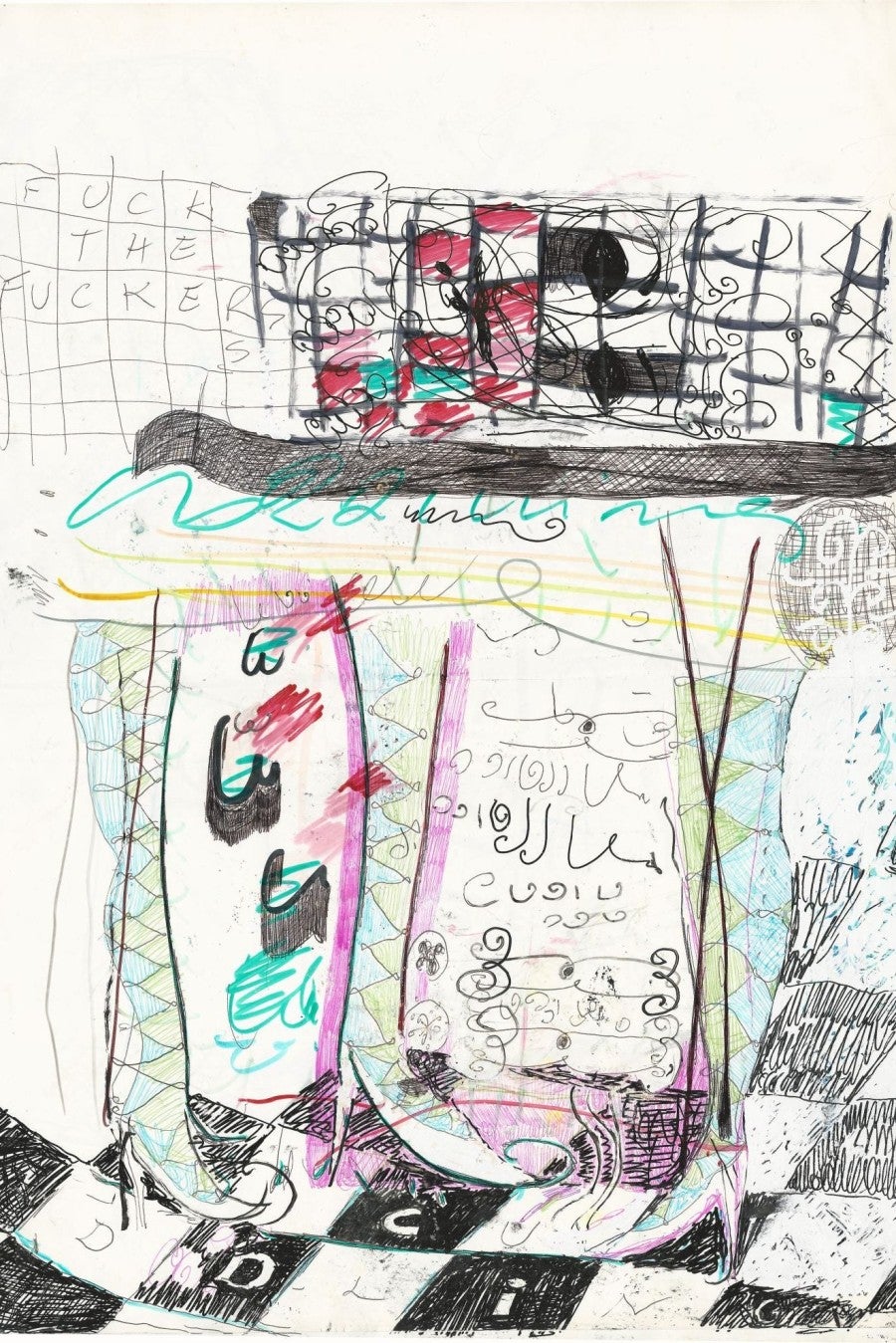

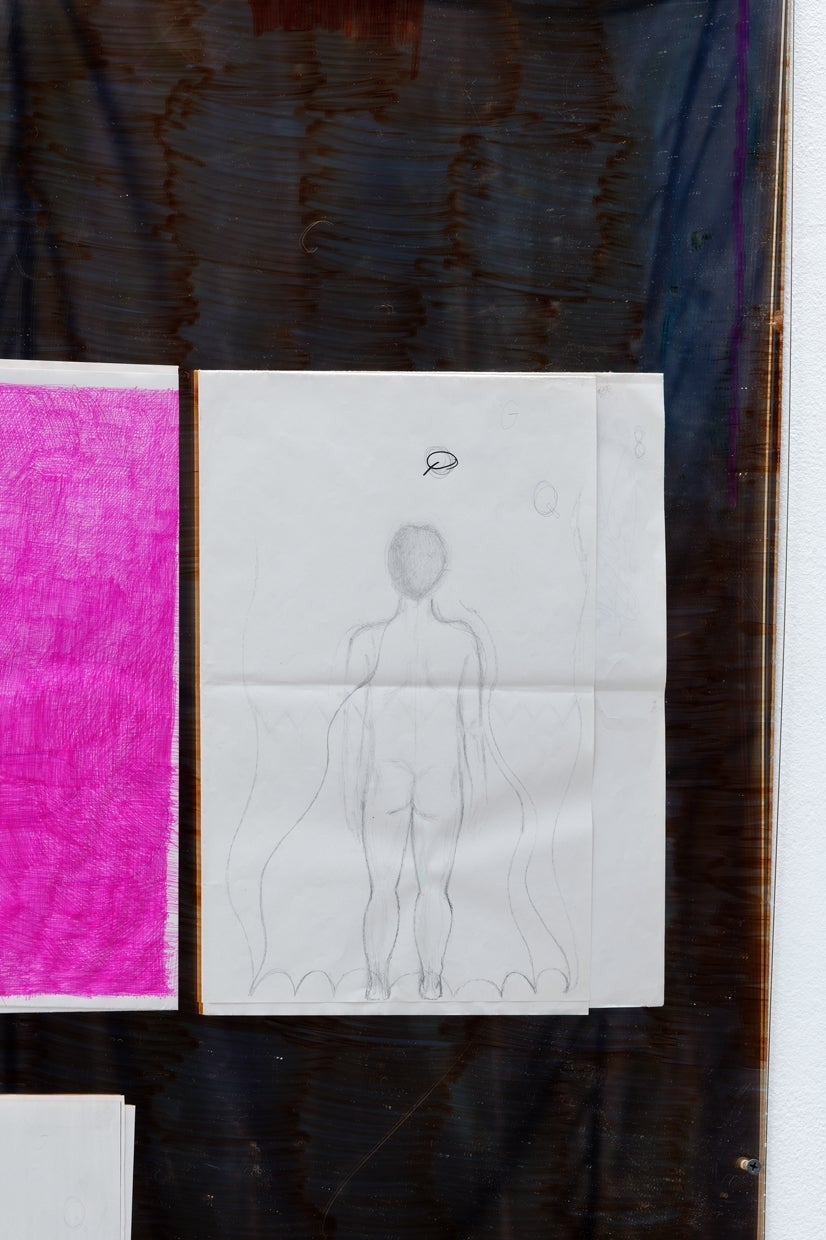

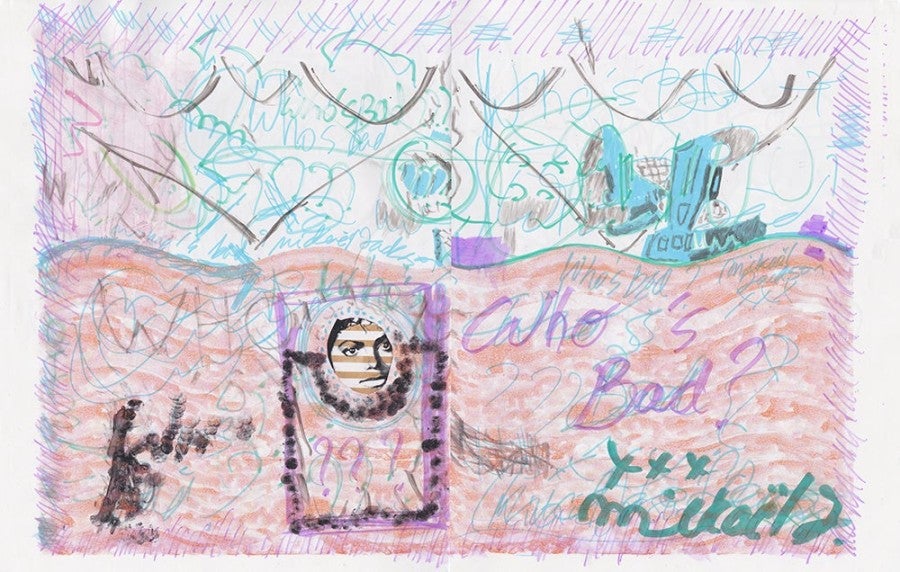

18. And indeed, actual Agnes Martin reproductions are present on the plexiglass. And so we must speak of the Americans: the Paul mentioned in the title of Anne Bourse’s first solo show in her gallery is the American artist Paul McCarthy, and Mike Kelley is also an important figure for her. With both artists we see the use of installation as a site for personal fetish, and the injection of an imagined or assumed time-based practice into a static end-result. The sketch books which Anne Bourse flips through, apparently randomly, in her address to the Basque students are clearly an important part of her daily practice. She loves to doodle in a seemingly aimless or unconscious way, and one imagines this as something therapeutic and compulsive, a process of generating and working through ideas. Later, presumably, comes an editorial stage in which Anne Bourse sifts through these drawings and — without improving or altering them — selects those she finds most interesting or relevant to a particular installation. In this sense she is both tribe and anthropologist, analysand and analyst, author and editor.

19. A satisfying combination of the programmatic and the personal emerges. In one mounted drawing in the gallery show, for instance, we see a curious sketch — almost William Blake-like — of a naked man seen from behind, his arms only half-drawn, dissolving into fabric flows or energy discharges, his bottom clearly defined and tight. The title is: Talking about shapely ass super heroes on the front face, we drew different styles of dick on the back, 2021.

20. Another work — entitled Ce soir les voitures roulent à l’envers, 2021 (This evening cars are driving upside down) — is a wall-mounted cabinet in felt-pen scribbled purple, its door mysteriously ajar, offering a glimpse of a scarlet interior. On the outside is placed a small work, also in ballpoint pen, its colours beautifully complementing those of the cabinet, its forms elegantly curled. I sense some of the generous utopianism of the late 1960s and early 1970s: Pucci prints, the psychedelic visions of LSD. The only other artist I can think of who combines these colour associations so evocatively is Mika Tajima, who works in New York with an experimental rock collective called The New Humans. Perhaps as a musician myself I respond particularly to this palette because of its cultural associations with the late 1960s: The Beatles and Pink Floyd at Abbey Road, my own early felt pen doodles, or the brooding yet vibrant quality of 1960s children’s books by, for instance, the Czech illustrator and puppeteer Jiří Trnka.

21. Sometimes Anne’s drawing style reminds me, strangely enough, of early Andy Warhol works, his commercial illustration period dominated by blotted-ink line drawings of cats and shoes, when he revealed an interest in twee cuteness and worked hard to charm art directors with little gifts. The motifs that recur are friendly and charming: a liquid wave, eyes, chess boards, polka dots, or the scroll-like shape I call a « curlicue », but which is better described as a volute like the ones seen on the capital of ionic order columns. The overall impression is of inwardness and tender-mindedness: baroque daydream.

22. In stark and perhaps satirical juxtaposition to this is the project involving « Brain, a journal of neurology ». This journal stands as a dialectical pastiche of the opposite attitude to the whimsical dreamscape of Anne Bourse’s drawings, setting up a contrast between the objective and the subjective, the fact-sheet and the dreamscape. An avid doodler (often while speaking on the phone), Anne Bourse is fascinated by the links — described in their different ways by neurology and psychoanalysis — between conscious and unconscious ideation. We might perhaps want to remember André Masson’s term « automatic drawing », or Paul Klee’s « going for a walk with a line »4. For Anne Bourse, it is rather the influence of Matt Mullican, an artist she adores when he becomes “That Person” to draw while hypnotised. Anne explained to me later that she had a brain accident a few years ago and spent some time in a hospital where she was cared for by a neurologist who wrote in the real Brain journal, published by Oxford University.

23. In the 1990s I became friendly with the British artist Georgina Starr, who inhabited a liminal, twilit zone at the edge of the Young British Artist movement and never quite achieved the banal fame and mainstream eminence of her friend and studio neighbour Tracey Emin. I am sometimes reminded of Georgina Starr’s approach when I read about what Anne Bourse described to Palais magazine as her « secret, feral inscriptions… the chosen affinities, which make up the fictional community in which I work »5. In Starr’s The Bunny Lakes series (1999-2003), for instance, she developed a series of works in various media inspired by a 1965 Otto Preminger film about a schoolgirl’s disappearance, and in the 2017 performance Androgynous Egg she staged a mini-opera in a darkened room decorated with eggs, portable paper breasts and singers in high-necked satin dresses in Victorian style.

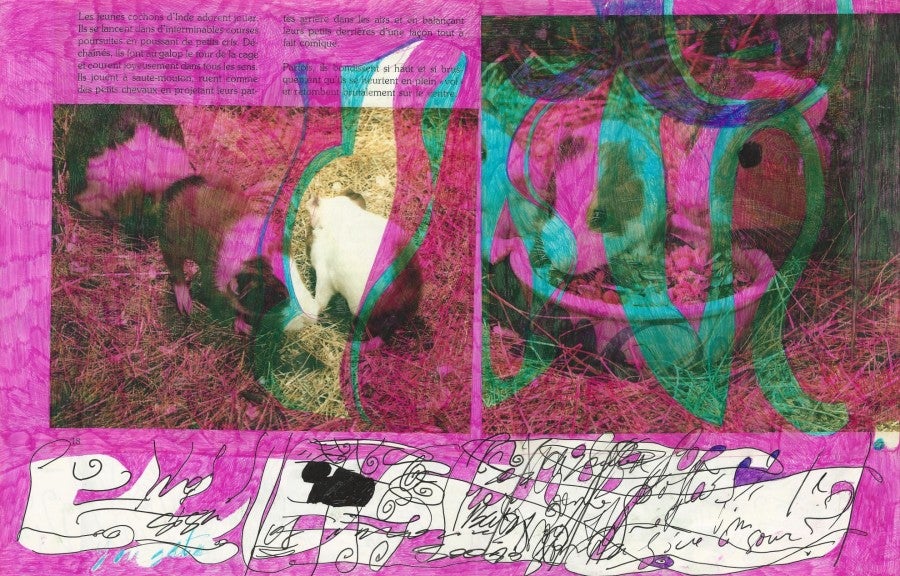

24. When I asked Anne Bourse how she first got interested in the Russian formalist Viktor Shklovsky, she told me that it was through a friend called Olivier, and that she was only interested in Shklovsky’s imaginary amorous correspondence with Elsa Triolet, and hadn’t read his books on literary formalism. I sensed a kind of mise en abyme: might this formalist incorporation of the romantic sentiment of a noted formalist itself have been the result, not of formalism, but of pillowtalk? Mise en abyme is, according to Wikipedia, « a formal technique of placing a copy of an image within itself, often in a way that suggests an infinitely recurring sequence ». The Shklovsky-Triolet correspondence appears in Anne Bourse’s work as a series of photocopies.

"I don't know if I can say that my work is political, in the sense that it is often wildly solitary in its construction"

25. The list of reappropriated or altered materials Anne Bourse gives Palais magazine is worth reproducing here as a subset:

a. A journal of imaginary neurology.

b. Jack Spicer’s love letters to a male lover who has apparently fled.

c. A book by Jimmie Durham « decorated » then reprinted on her wonky printer.

d. Advertisements for real or imaginary bars.

e. A book about guinea pigs dyed pink in homage to Butt, the gay magazine which was printed on pastel pink paper.

f. Rather an empty magazine inhabited by half wiped-out conversations with her friend Greg via Messenger.

g. An imaginary brochure for the Japanese restaurant downstairs from her place.

h. A book about a contemporary artist.

i. A Russian novel.

j. A children’s book.

k. A magazine about a cult in her neighbourhood.

l. A book about rabies.

26. This Palais de Tokyo interview also contains an excellent general statement from Anne Bourse: « It is the way things hook up and spread out, contradict each other and become dissonant, and all the stylistic contrarieties that this leads to. Let’s say I’m a language interspecies-ist, and also a bit perverse. I address people through one thing to be able, in fact, to talk to them secretly about something else. » This makes me think of the approach of psychoanalysis, in which we speak the conscious in order to reveal its links with the unconscious.

27. Anne likes to cite Hélène Cixous’s thought about translation being like a letter H, the rungs of a ladder connecting an idea in one language with an idea in another. Translation was a key part of Nicolas Bourriaud’s early 21st century concept of « the altermodern », a refocusing of post-postmodernity so alternative that nobody mentions it today. The central themes of the altermodern were a rebooted globalisation, cultural creolisation, and translation. But perhaps a better association would be the Speculative Poetics of Armen Avanessian, a platform for publishing and translation founded in 2011 which asked how a sort of « speculative drawing » might work by thinking « not about but with art »6. Like the later, more visionary and syphilitic Nietzsche, the accelerationists have left the highest philosophical task to the artists.

28. But art refuses a pompous and central role, knowing how easily co-opted that can become. Asked if her work is political, Anne Bourse is wisely evasive: « I don’t know if I can say that my work is political, in the sense that it is often wildly solitary in its construction, » she told Palais magazine. « But if there is a community of language, even a fictive one, then it is perhaps there that I’m involved, with the choice to gather exterior spaces without making them moral, but making them desirable, or making them desire themselves… Not being clear is important. I have the feeling that the only place where you are free is a tiny blind spot, a nook in the brain, and maybe in art, when you so decide — and precisely not in the political and moral discourses that some works produce. »7 This brings to mind Michel de Certeau’s distinction (in his 1980 book The Practice of Everyday Life) between the strategic and the tactical: strategies are institutional and stolid, whereas tactics are personal and cunning.

29. With Certeau’s idea of the tactical we return to the adjective « fugitive » in the title of the Palais de Tokyo group show at which I first saw the work of Anne Bourse. Her practice avoids grand statements and pompous authority, preferring informal tools and methods (felt pen, doodles). Rather than embracing a programmatic theme (the victim narratives of identity politics, for example) it sketches personal and poetic links between areas of personal interest (Shklovsky, neuroscience, love, obsession). Rather than using the established vocabularies of fine art, it delves into humble and practical materials from craft and industry, approximating pragmatic forms (the mattress) with a deliberate awkwardness. Rather than studied naivete, however, this is a kind of cunning: in Certeau’s sense it is the cunning of the tactical, described by adjectives like haphazard, makeshift, fuzzy, cunning, evasive, subversive, personal, folksy, unpredictable, provisional, temporary, slippery, subtle and ungraspable.

30. In a video conversation with Anne Bourse she recommended that I contact Benjamin Seror, a friend of hers who had written a fiction in which Anne Bourse is a television producer in Hollywood who writes from details of conversations, held every morning between the parking lot and the coffee machine, with scriptwriters pitching new trivial episodes. This fiction began with a deceptively simple declaration: « Unlike many of my friends, » Seror wrote, « Anne is not a fictional character. She exists. » Since I am currently living in Athens, and Seror — according to Anne Bourse — is also living here, I decided to put out feelers in the community. I asked Athens artists, designers and gallerists if they had ever heard of or met Benjamin Seror. Nobody had, although they all thought he sounded like a very interesting person, and expressed surprise that he could have escaped their notice. And so it occurred to me that Seror — a character who admits that most of his friends are imaginary — might himself be a figment of Anne Bourse’s imagination, or perhaps a real person reappropriated by Anne Bourse for her own ends. But by this same logic, perhaps I am also a fiction created by Anne Bourse for her own purposes? The question lingers troublingly as I walk through a partially locked-down Athens made up (amongst other things) of mattresses, photocopies, felt pen and volute.

Pierre Cabanne, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, 1966.

Adam Phillips, The Essay, On Excess, BBC Radio 3, 2015. www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00dpg4x

Various gallery websites and [Conférence] Anne BOURSE - ESAPB - Janvier 2018: www.youtube.com/watch?v=ToPAIzCYDJg

André Masson, Le rebelle du surréalisme: Écrits et propos sur l'art, 2014. Paul Klee, Pedagogical Sketchbook, 1953.

Magazine Palais #30, Futur, Ancien, Fugitif, (October 2019), p. 143.

From blurb on Sternberg site for Armen Avanessian and Andreas Töpfer, Speculative Drawing: 2011–2014, www.sternberg-press.com/product/speculative-drawing-2011-2014/.

Magazine Palais #30, Futur, Ancien, Fugitif, (October 2019), p. 175.

Magazine Palais #30, Futur, Ancien, Fugitif, (October 2019), p. 143.

From blurb on Sternberg site for Armen Avanessian and Andreas Töpfer, Speculative Drawing: 2011–2014, www.sternberg-press.com/product/speculative-drawing-2011-2014/.