The Distance from the Beach

It’s August and I’m sitting at my desk.

There are so many cultural specificities to this. Mid-July, I was in France, and the polite thing to do, the solution to the problem of conversation, was to ask about vacation. Plans: where, when. Beach, mountain. Family or friends, near or far.

It’s August and I’m in New York. It’s hot. I swim outdoors every day and on days when I don’t have a deadline, I bring a book to the public pool and read for a short while before I cycle home, eat lunch on my fire escape, and get back in front of my computer. There is a special emptiness to the city in August: your friends are gone, there are seats in restaurants, everyone hiding from the heat, the subway a metallic cool.

There’s a beach in New York. At the end of the day on the A train, next to the commuters, are some late-to-leave beachgoers. Salt in their hair, sand in their shoes, the marks of wet fingers on their slightly damaged books.

Staying in town may be an answer to the tension built into vacation. This thing, so longed-for, so looked-for, so often discussed and dreamed, when it arrives, is always on the brink of disappointing. Expectation, after all, is the emotional antonym of disappointment: the one lurks behind the other.

Blue

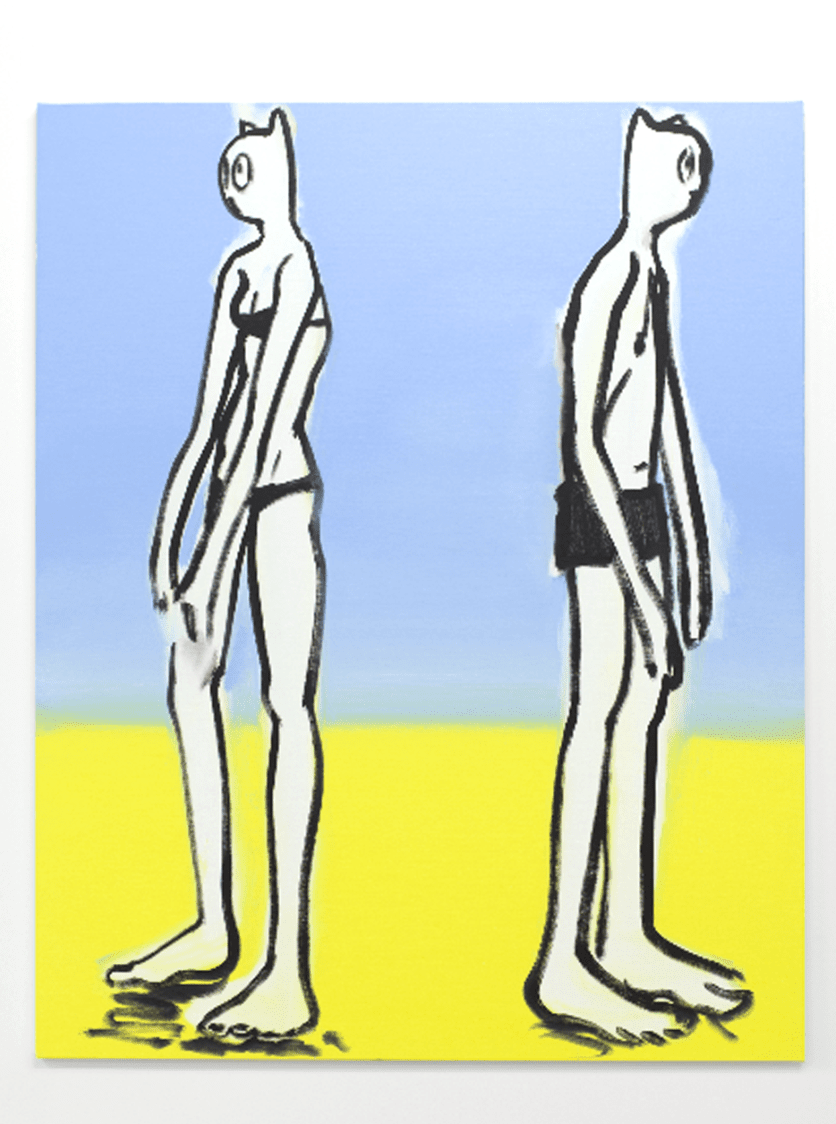

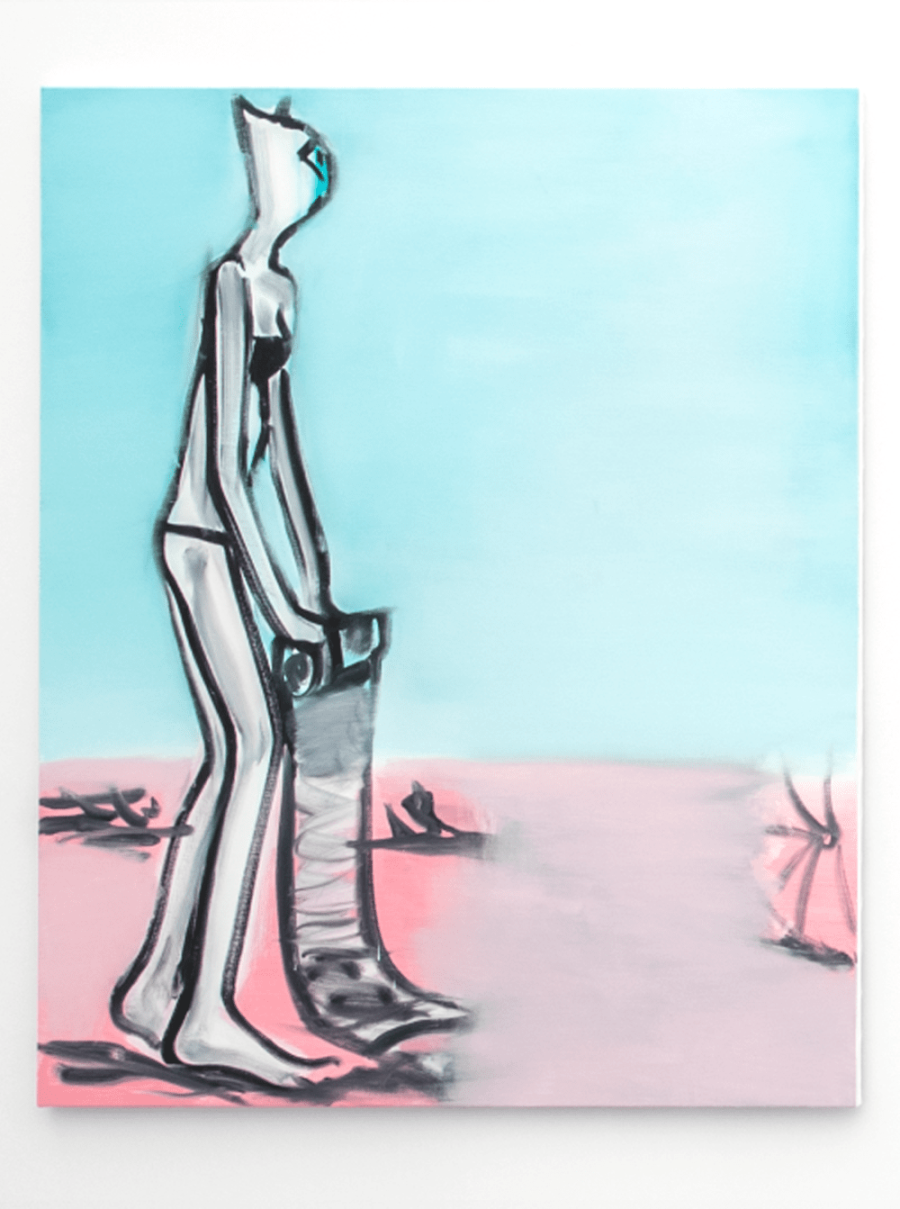

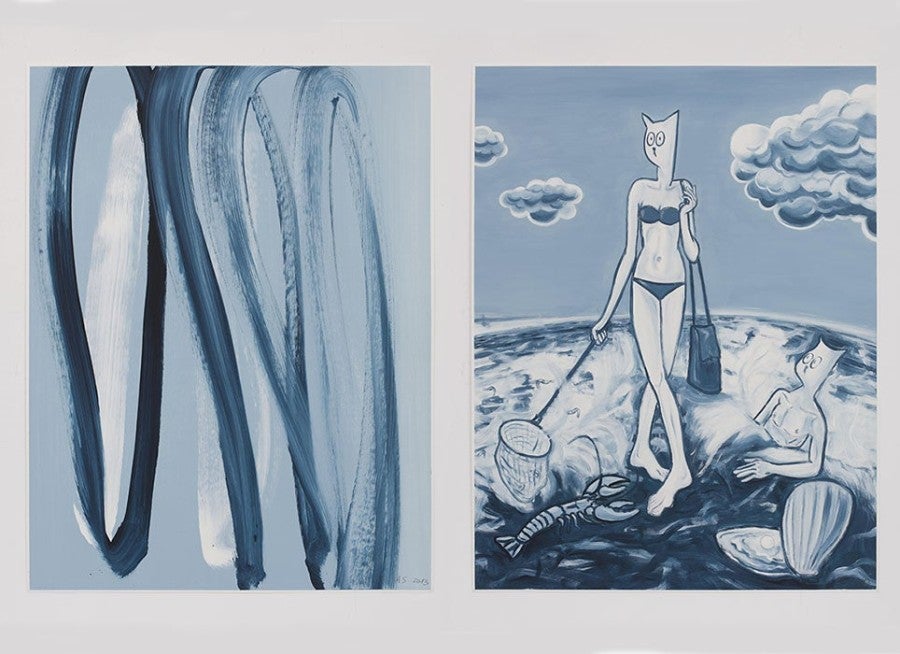

When you go to the beach, nothing happens. Alain Séchas describes it as a horizontal place: the horizon stretches long and level, the people lying down, their towels flat against the ground. Most of Séchas’s beach paintings are vertical, a refusal of said horizontality, they fill the frame to the brink and stop the time that is already moving so slowly in the sun. Here’s a teenage couple holding hands, behind them, in the distance, the object that gave the painting its name—red buoy (Bouée rouge, 2005). You wouldn’t know that they were teenagers—their faces are cat faces, they have no hair that would turn gray, no wrinkles on their faces. But their bodies are lanky and they hold hands awkwardly, loosely, still never letting go. The girl wears shorts and a red T-shirt; the boy knee-length jeans. She’s a step ahead, but she looks back, glancing toward him. He is apprehensive. Their faces may be abstracted, simplified to the form of a cat, but their expressions remain familiar, recognizable, human. The sea—turquoise, so translucent their legs seem deep within it (their step is too light to be wading in water, they are firmly on the ground)—almost merges with the sky, a blue so deep it’s just a shade away from water.

“To be blue is to be isolated and alone,” writes William H. Gass in On Being Blue: A Philosophical inquiry, 2014. Gass examines associations (“Blue pencils, blue noses, blue movies,” it begins); words and their foredoomed failure to describe (“we have more names for parts of horses than we have for kinds of kisses”); and emotions (“love is a nervous habit”). On Being Blue—the book is a work of expansion, or a work of paying attention. It begins with blue pencils and ends (this is no spoiler) with clocks that slow down, a pouring rain, perhaps a smoke stack from a factory, “and everything is gray.” On Being Blue—it’s an exercise in exhausting one thing, and ending up at its opposite (remember, opposites lurk behind).

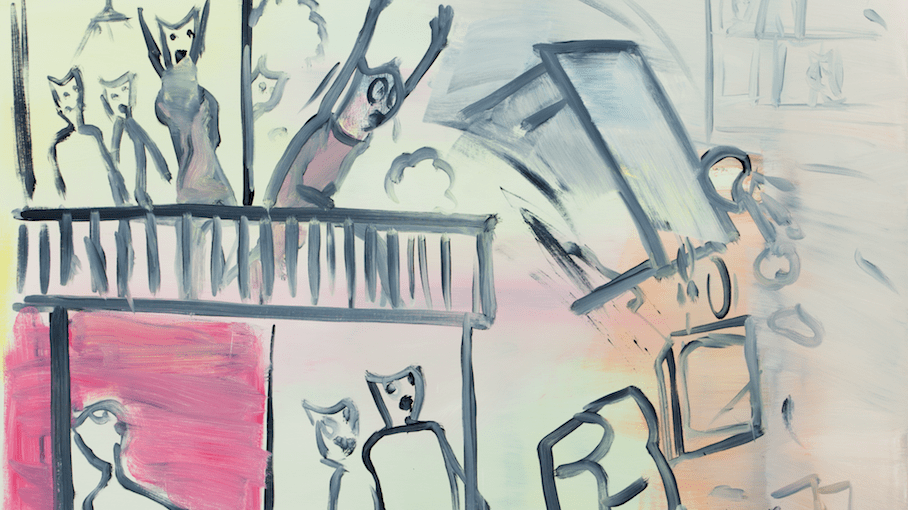

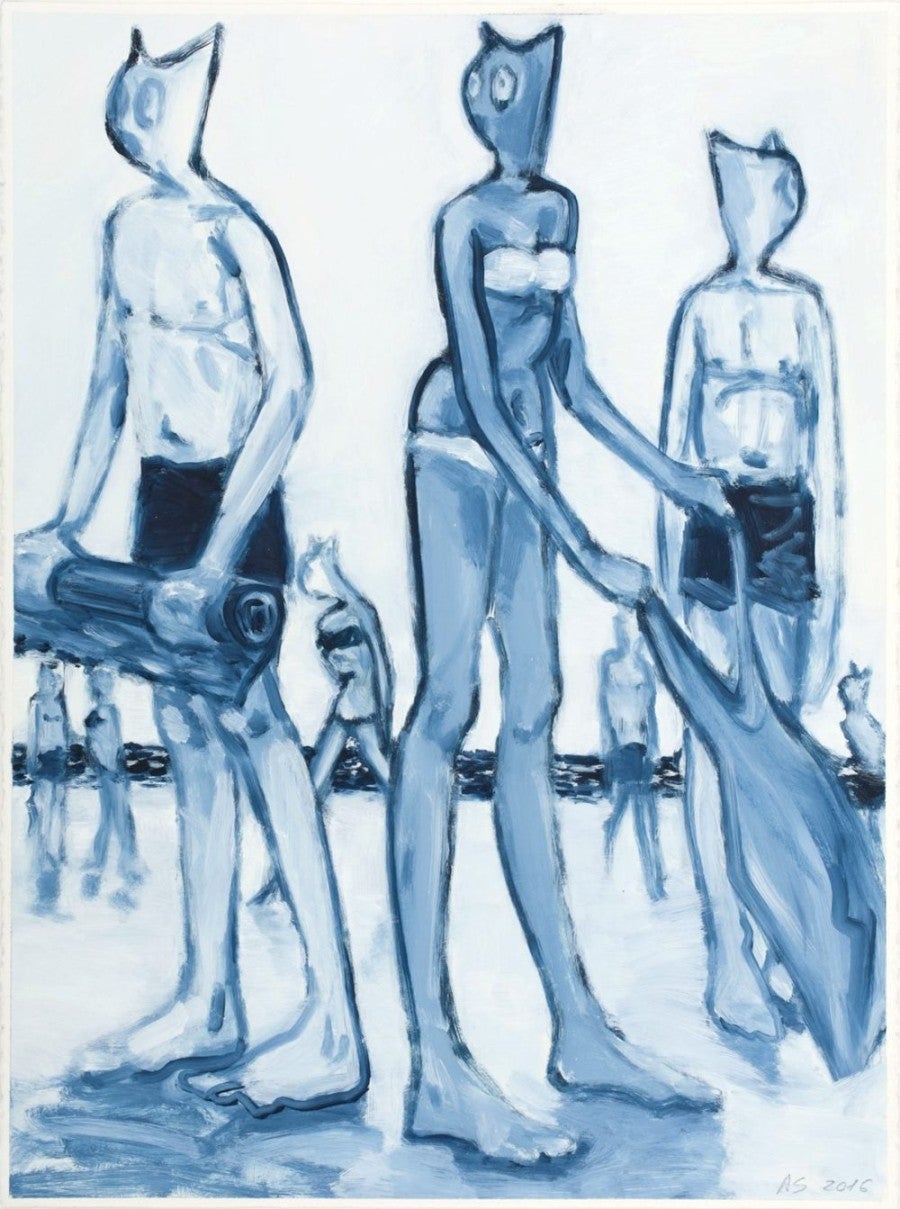

There’s a blue series in Séchas’s beach painting, and these paintings are a direct reference to a famous predecessor: Picasso’s Blue Period canvas, The Tragedy (1903). In Picasso: A man, a woman, a child, and all the sadness in the world. The adults look down to the ground, the child at the contour of the woman. Their bodies are fragile, enclosed, hunched. Is anyone as fragile as they are? The rawness of emotion in modern paintings has seeped into our culture. We talk about loneliness and imagine Starry Night—that sole church steeple, the large, haunting swirl of the sky. But we no longer trace that icy sentiment in contemporary paintings, no one is that genuine anymore. In Séchas’s Blue Beach paintings (2016), the figures always look beyond the picture frame, like action is always happening elsewhere. Think of scenes in movies—a storm approaching, a danger—and one thing the people all share in those moments is missing here: the figures do not look at each other. They don’t point somewhere, they don’t seem to shout to each other. They don’t share. They are all alone (just, together, near each other). They are bathers, stuck in that horizontal, endless landscape, maybe stuck in the representational history they form part of: bathers, like the subjects of Renoir, of Cézanne. Stuck in the act.

Comics

Séchas's work looks at the world in a way that recognizes its internal humor and weirdness.

What is required, what is enough in order to communicate an emotion? Séchas’s lines are quick, decisive. What is hint enough, descriptive enough—how much do you have to tell in order to construct a story? The rapidness of the gaze and of the brushwork, the cat faces, the action, all of these have the quality of comic strips. Or, not the whole strip: an isolated moment, a single frame, stripped of speech. In one of Séchas’s painting, a text appears: OYSTER THERAPY (Oyster Therapy, 2005). The therapy session is not for oysters, of course, it’s for three humanoid cats, lying in the open shells of three oysters in an institutional-looking room with checkered floors and a prominent door. Funny to say about paintings where cat-humans can take dogs on a leash for a walk, but Oyster Therapy is the most inexplicable of them all. Are these huge oysters or tiny human-cat figures? Is it happening in a dollhouse? It’s a painting that encapsulates Séchas’s work: it looks at the world in a way that recognizes its internal humor and weirdness.

The caricature or comic-like nature of the paintings only serves to support this: in lieu of using these techniques to critique the world, like Honoré Daumier, or like Batman (who needs to step in where humans can’t), Séchas in these paintings looks at the world and pokes fun at it—but never from a distance. These paintings are fully embodied, they’re part of the world, they just register its possibility to be strange and surprising. The comical is a form of attention: the joke requires knowledge of its components. And it requires just a touch of truth—the process of telling a joke is the process of pulling the rug from under the listener’s feet, just as they started to identify, or recognize, the scene set by the teller.

The first cat Séchas made is a joke incarnate. Le chat écrivain (1996) is a sculpture of a cat at his desk, quill in hand and ink bottle and a candle on the table. He’s just finished a letter to his sister, and he gazes again at a canvas set in front of him, the portrait of a visibly older, stern cat in a hint of a suit. The letter reads, “My dear sister, I have just finished the portrait of our father. Finally, the goal has been achieved! I haven’t the words to describe this masterpiece.” It goes on: “a colossal effort of the memory, the synthesizing of the good traits of our loved papa.” The language is exaggerated as is the scale of the tiny chair and desk the cat sits at, his paws-feet huge as he crouches, his tail emerging from the chair’s back and trailing around it. He’s described as a writer, écrivain, but he’s obviously a painter. He’s also obviously not real: a figure of a nineteenth-century artist (had this cat been dressed, like his father in the painting, you’d imagine he’d be in paint-splattered clothes, cravat included), the cat personifies not an artist, but a performance of being one. The overblown language in the cat’s letter—“the moustache really gave me a hard time”—only serves the joke more. The lack of self-awareness—he is a cat, after all, what would you expect—makes him not the subject of the joke, but a participant in a history of imaging of artists that is the real gist.

If every joke has a bit of truth to it, then to see what is serious, what is genuine, is the real work of listening.

A Change of Scene

“To make things really white, you need silk thread,” Séchas explains to me. We’re at the Manufacture des Gobelins, a national museum and still the site of production of tapestries, which has occupied its current site in the 13th arrondissement in Paris since the seventeenth century. We had been looking at an exhibition on the history of Gobelins-made tapestries and just reached its last room, where a reinterpretation of one of Séchas’s abstract paintings, woven by hand, here at Les Gobelins, into a lush tableau, is displayed. A Map of Japan (2012–18) is an abstract with a fair blue background, and strokes of pink, brown, yellow, green, and white. It’s not a figurative painting, yet the title again conveys another meaning: a sense of place. I can almost smell the cherry blossoms, since the association was the first to come to my mind, and it lives on—the pink, the white, the brown and greens: a sole cherry blossom against a slightly clouded sky. Spring. It is woven in wool and silk, translating thick brushstrokes into textured fabric. The white, indeed, shines brightest.

In 2006, Séchas stopped painting cats and making sculptures—which he calls “volumes”—and focused his attention on abstractions. “I thought of it,” he explains, “as an erasure of what came before.” The abstract paintings—all untitled and numbered—combine black strokes with strong coloration. They could encompass whole histories of painting in one work, a composite of memories of Nicolas de Stael and Piet Mondrian at once. Barnett Newman and early Jackson Pollock meeting on a single canvas. Like the beach paintings, there’s an expressionism to them that feels historical, but there is also a sense of holding back, of an artist trying out all possible outcomes. Later on, in 2015, when Séchas returned to painting cats, colorful backgrounds appear behind them. Here’s a De Stael background, thick squares of color, with a cat with a shopping cart ahead of her. There, a geometric backdrop with a cat-woman in a knee-length skirt looking at a round aquarium, the kind used to keep goldfish, containing a smiling octopus that fills it to the brim (the humor of the cat-people having pets will never stop making me giggle). In all of these, the backgrounds show the bold colors Séchas used in his abstractions, and the figures are composed of simple, quick black lines, more cartoonlike than ever.

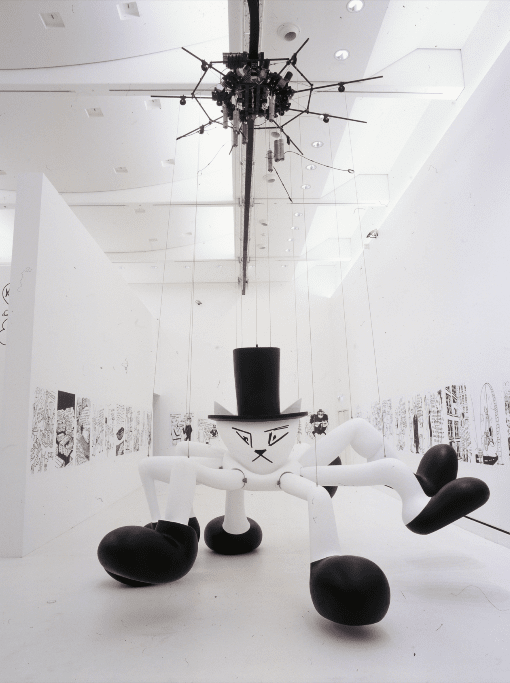

Why the pause, the reinvention? What Séchas talks about, the erasure of what came before, is a form of exploration of something that wasn’t in the work initially: the possibility of encapsulating all movement in the canvas itself. Before the abstractions, Séchas’s sculptures were all made, like Le chat écrivain, in white polyester. Even when they were painted, like the public sculpture La Cycliste (2005), of a female cat in black shorts and a pink top, sitting on a blue bicycle in front of the Royal Galleries in Brussels, they still responded to the whiteness we associate with Greek and Roman marbles. Even when they were kinetic, they had to have a path delineated through the exhibition, like the mechanical spider who roamed Séchas’s exhibition at the Musée d’Art Moderne et Contemporain in Strasbourg, linked like a string puppet to a mechanical control in the ceiling that moved and pushed forth its eight legs (L’Araignée, 2001). (This path then becomes part of the joke, evidently in the sleepwalking cats, Les somnanbules, 2002, who roamed the exhibition space, as if walking in their sleep, only always linked to a track on its floor.) The abstractions allowed Séchas to explore all these aspects—motion, action, color, and different histories of art—in a single medium: painting.

When the cats reappear, they combine all of his conclusions—the color, the movement, the narrative—back in the familiar form: paint on canvas. It was that thing so many people wish they could do, when they go on vacation, when they try to make a difference in their lives: leave in order to come back, right where you started, only changed.

On Cats

“Do you have cats?” I ask. Séchas looks at me, and for a second, I wonder if he doesn’t see why I’m asking. “I don’t particularly love them,” he humors me and answers the question. “Not more than dogs?” I ask. “Not more than humans.”

Séchas does not have a single answer as to why, in his art, he substitutes human faces with those of cats. He talks about reduction, how the removal of the face is a way of attracting a viewer’s eye to the composition. “It’s the banality, the sameness of those faces that I paint” Séchas says, then contradicts himself immediately, and says, “I use that word, fascination, a lot.” The cat faces are also fascinating: the face of the cat is from all the comics you’ve ever read, it’s the Ancient Egyptians worshipping half-feline half-woman deities. There’s something childish about the cat faces—the infantile is a very primal thing in us, Séchas points out—but also enigmatic. Think about the eyes of a cat, Séchas says to me. When you go to the optometrist, they tell you, look far.

On Humans

We see more of ourselves in them than their comic-like abstraction would suggest...

Marilynne Robinson’s novel Gilead (2004) is a long letter from an aging father to his young son. The father is a priest, and he writes to his son about growing old, about his family, about his life before he met his wife, before the son was born. The father writes about how he saw the world, and how he saw his son. And in one section, he writes to his son about his sister when she was a baby. “She was such a little bit of a thing,” he describes, then tells the son about how one time he held the sister, and she opened her eyes. I know babies can’t see much, the father says, but at that moment he recounts how she looked right into his eyes. “Now that I’m about to leave this world, I realize there is nothing more astonishing than a human face. … Any human face is a claim on you, because you can’t help but understand the singularity of it, the courage and loneliness of it.” The father is a priest, he writes about religion and theology a lot, but the novel is meant to be a personal statement about life and the world as we experience it. “I have been thinking lately how I have loved my physical life,” the father writes. Maybe because of its religious bend, there is a strong sense of humanism in the novel. There is an ease to being human.

And if there is nothing more astonishing than a human face, what could abstracting it—in art—mean? Not like the example of Picasso (again!), deconstructing the faces of his sitters in order to compile them from all possible angles, but like these cat faces, which become both an anyone and no one. These figures, men and women with the faces of cats, hold cell phones, shop at the grocery store, go to the beach. Like Le chat écrivain, they can become representation, a humorful depiction. More often, though, we see more of ourselves in them than their comic-like abstraction would suggest. That’s the other thing about the ease of being human: we see humanity in everything. We see ourselves in things.

There is a distance from which Séchas paints: in a drawing titled Hans Jean Arp (2000) a group of cat-youths (art students?) are kneeling to an Arp sculpture. Like a BOOM! or KAPOW! in a comic strip, the writing here reads ARP! and HANS JEAN!. Next to the students are two older cat-men in suits, saying, “It’s the Hans Jean Arp Sect!”

Séchas, who taught art for a long time, looks at his own experiences, and histories, and renders them a joke. Freud said that there is a slight hostility in humor. In Séchas, the humor comes, at times, from looking at the world from a distance, poking fun at its incongruities. But even if there is darkness, there is always a proximity, as well, which is in the humanism of Séchas. Freud talks of hostility, but there is also an intimacy to a joke: to laugh, you have to be on the in, you have to understand. Part of the joy of Séchas’s paintings is that you, the viewer, are never excluded from the joke.

Séchas is an observer, he gazes at the society around him, and inserts the world he sees into the parallel, sweet and funny cat dominion of his paintings. About one of the bather works, Séchas says he saw it in real life. Baignade au château (2015) is a woman in a black bikini, holding a towel by a sketchy body of water, a fragment of a castle behind her. “I saw it, somewhere in France,” he tells, and describes a group of teenagers bathing in the fountain of a chateau. “It was shocking,” he explains. (To use something for a purpose it wasn’t made for can throw anyone off.) His cat-woman bather seems tentative, her movements contained, her hesitance showing. She is not a group of youths, acting on a whim, allowing each other a sense of freedom rooted in the fact that they’re in it together; she is a version of a memory, and her abstraction allows for that scene, that memory, to become more than that one moment.

An Inconclusive List of Artists Who Painted the Same Theme Over and Over Again

Pierre Bonnard and Alex Katz painted their wives throughout their careers. Bonnard’s wife never ages in his paintings (Raymond Carver wrote a poem about it, how Bonnard painted her, “As he remembered her young. As she was young.”) Katz painted his wife over 200 times in the sixty years since they’ve met. Giorgio Morandi found endless inspiration in the houseware around him, painting water pitchers and glass bottles in chalky colors again and again. On Kawara saw beauty in every day, painting dates and sending postcards marking the passage of time by telling his friends and associates when he got up that morning. Cézanne: the paintings of Mont-Sainte Victoire overlooking his hometown, Aix-en-Provence. Monet: his backyard.

At Séchas’s exhibition, “Alain Séchas. Passe-temps” at the Musée de l’Abbaye Sainte-Croix in Sables d’Olonnes, a beach town on the Western Coast of France, a woman asks him about his abstract paintings: est-ce que c’est la fin des chats?

Are the cats to Séchas what the kitchen items were to Morandi? The water lilies to Monet? Séchas’s subjects are human, they could be called portraits, or group portraits, the only thing missing is that specificity—Robinson’s “singularity”—that we associate with the face of another human being. But like Morandi, they are the choice of one window from which to explore the endless landscape of the world.

A last question: What kind of patience does it take to go to the studio, every day, and find something there, time and again, in the same metaphor?

August

Maybe it’s like looking straight at the sun.